This answer is supposed to be a complement to the answer offered by Yuval Perez, with the following observations:

I am not convinced of the proof given in the link

Is it true that a boundary of a simply connected and bounded set is connected in $\mathbb{C}$?,

so my answer essentially attempts to fix the part of Yuval's answer that uses that link.

As I mentioned in a comment below Yuval's answer, I am not entirely comfortable with the claim that the set denoted $D$ in Yuval's answer is indeed simply connected (after $\infty $ is added to

it). Unfortunately I have no easy fix for this, hence my own answer is dependent on this point.

This said, as noted by Yuval, it suffices to prove the following:

Lemma. If $U$ is a nonempty, open, bounded, simply connected subset of ${\mathbb R}^2$, then the

boundary $\partial U$ is connected.

Proof.

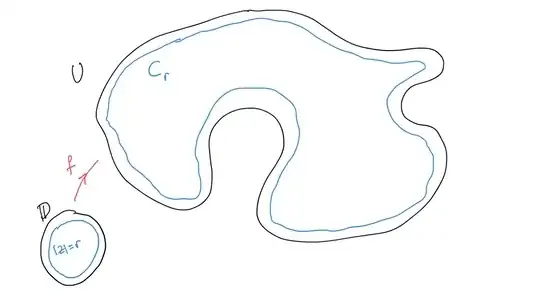

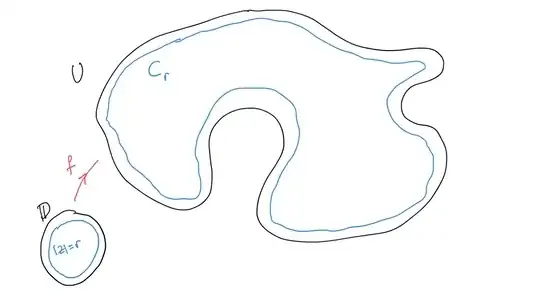

Identifying ${\mathbb R}^2$ with the complex plane, and using the Riemann mapping theorem, there is a bi-holomorphic

map $f$ from the open unit disk $\mathbb D$ onto $U$.

For each real number $r$ in the interval $(0,1)$, consider the subset of $U$ defined by

$$

C_r= \{f(z): |z|=r\}.

$$

Roughly speaking, we will prove that the $C_r$ converge to $\partial U$, and since each $C_r$ is connected, so

will be $\partial U$. The details are as follows:

Fixing $\varepsilon >0$, denote by $V_\varepsilon $ the open set

$$

V_\varepsilon :=\{x\in U: \text{dist}(x, \partial U)<\varepsilon \}. \tag {1}

$$

We then claim that

there is some $r_0\in (0,1)$ such that, for every $r$ in $(0,1)$, with $r>r_0$, one

has that

$$

C_r\subseteq V_\varepsilon .

$$

To prove the claim, observe that

$$

K_\varepsilon := U\setminus V_\varepsilon = \{x\in U: \text{dist}(x, \partial U)\geq \varepsilon \}

$$

is a compact set (Reason: every sequence in $K_\varepsilon $ has a sub-sequence wich converges in $\bar U$,

say with limit $x$, because $\bar U$ is compact. By continuity $\text{dist}(x, \partial U)\geq \varepsilon $, so $x$ is not in

$\partial U$, meaning that $x\in U$).

The collection of sets

$$

D_r:= \{f(z) : |z|<r\},

$$

for $r$ ranging in $(0,1)$,

clearly forms a cover for $U$, and in particular also for $K_\varepsilon $. Since the $D_r$ are increasing, by compactness there is

some $r_0$ such that $K_\varepsilon \subseteq D_{r_0}$, and hence also $K_\varepsilon \subseteq D_r$, for every $r\geq r_0$. It follows that

$$

C_r \subseteq U\setminus D_r \subseteq U \setminus K_\varepsilon = V_\varepsilon ,

$$

as desired.

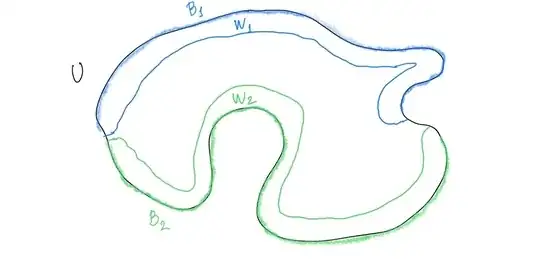

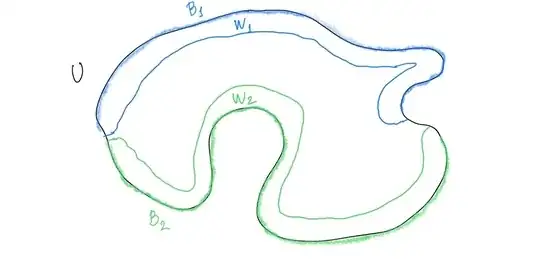

Assuming by contradiction that $\partial U$ is disconnected, write $\partial U=B_1\sqcup B_2$, where $B_1$ and $B_2$ are

nonempty,

closed sets, "$\sqcup$" standing for disjoint union.

Since both $B_1$ and $B_2$ are closed and bounded, they are compact and hence their distance is strictly positive. In symbols

$$

d:= \inf\{|x-y|: x\in B_1, \ y\in B_2\} >0.

$$

We then consider, for every $i=1,2$, the open set

$$

W_i=\{x\in U: \text{dist}(x, B_i) < d/2\}.

$$

Evidently $W_1\cap W_2=\emptyset$, while $W_1\cup W_2=V_{d/2}$ (as defined in (1)).

Taking $r_0$, as above, for the choice of $\varepsilon =d/2$, we conclude that for every $r$ in the interval $(r_0, 1)$, one has that

$$

C_r\subseteq W_1\cup W_2.

$$

Observing that $C_r$ is connected, we deduce that either $C_r\subseteq W_1$, or $C_r\subseteq W_2$.

However, it is a simple matter to show that, for every $i$, the set

$$

J_i:= \{r\in (r_0, 1): C_r\subseteq W_i\}

$$

is open. Since $(r_0, 1)= J_1\sqcup J_2$, we have by connectedness that either $J_1$ or $J_2$ coincides with

$(r_0,1)$. We then suppose, without loss of generality that $J_1=(r_0, 1)$, which is to say that

$$

C_r\subseteq W_1,\quad \forall r\in (r_0,1).\tag {2}

$$

Pick some point $x$ in $B_2$, and let $\{x_n\}_n$ be a sequence in $U$, converging to $x$. Assuming, as we may, that

$|x_n-x|<d/2$, we necessarily have that $x_n\in W_2$.

Write $x_n=f(z_n)$, where $z_n$ lies in the open unit disk $\mathbb D$. By passing to a subsequence, we may assume that

$\{z_n\}_n$ converges to some point $z\in \bar {\mathbb D}$. Clearly $z$ cannot lie in ${\mathbb D}$, because otherwise

$$

x = \lim_n x_n = \lim_n f(z_n) = f(z) \in U,

$$

but we know that $x\in B_2\subseteq \partial U$.

It follows that $|z|=1$, so $\lim_n|z_n|=1$, and hence there is some $n_0$ such that $n\geq n_0$ entails $|z_n|>r_0$.

This implies that, for $n\geq n_0$,

$$

x_n=f(z_n) \in C_{|z_n|} \subseteq W_1,

$$

by (2), contradicting the fact that $x_n$ lies in $W_2$. QED