Suppose $X\sim\mathcal N(\mu,\sigma^2)$. The first negative moment $\mathsf E(1/X)$ does not exist; however, we can define it in the sense of the Cauchy principal value:

$$

\tag{1}

\mathsf E(1/X)\overset{PV}{=}\frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sigma}\,\mathcal{D}\left(\frac{\mu}{\sqrt{2}\sigma}\right),

$$

where $\mathcal{D}(z)=e^{-z^{2}}\int_{0}^{z}e^{t^{2}}\,\mathrm{d}t$ is the Dawson integral. The nonexitence of the $\mathsf E(1/X)$ manifests itself in the sample mean as

$$

(\overline{1/X})_n=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{1}{X_k}

$$

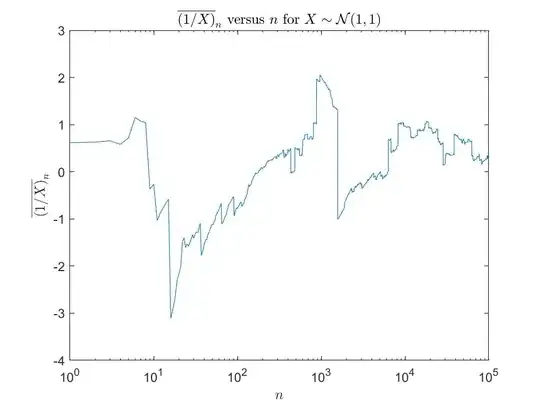

never settles down to any particular value as $n$ increases ($1/X$ is in the domain of attraction of the Cauchy law and therefore does not abide by the CLT). For example, consider the running mean generated from sampling $X\sim\mathcal N(1,1)$:

Because $|\sigma/\mu|$ is relatively large we regularly observe $X$ near zero and our sample mean never converges. However, in practice, this behavior is not always observed. Consider the same experiment except with sampling taken from $X\sim\mathcal N(6,1)$:

Because $|\sigma/\mu|$ is relatively large we regularly observe $X$ near zero and our sample mean never converges. However, in practice, this behavior is not always observed. Consider the same experiment except with sampling taken from $X\sim\mathcal N(6,1)$:

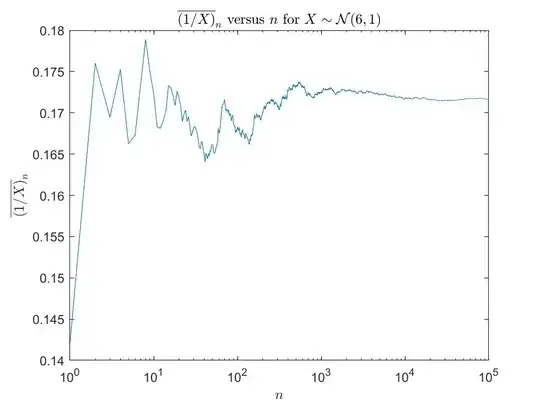

We see the sample mean does settle down with increasing $n$. Moreover, the value the sample mean is approaching is the principal value moment $(1)$. In theory, this behavior is just an artifact of finite sampling in that if we continue increasing $n$ we should eventually observe values of $X$ close to zero and our sample mean will be disrupted. However, no matter how large I make $n$, I never actually observe these values in practice due to the relatively small value of $|\sigma/\mu|$.

We see the sample mean does settle down with increasing $n$. Moreover, the value the sample mean is approaching is the principal value moment $(1)$. In theory, this behavior is just an artifact of finite sampling in that if we continue increasing $n$ we should eventually observe values of $X$ close to zero and our sample mean will be disrupted. However, no matter how large I make $n$, I never actually observe these values in practice due to the relatively small value of $|\sigma/\mu|$.

Does this make $(1)$ a useful analytical expression for the expected value $\mathsf E(1/X)$ so long as $|\sigma/\mu|$ is small? If so, what would be a coherent theoretical justification for such a statement?

For example, if $|\sigma/\mu|$ is small, we may not observe the set $\{X|\epsilon>|X|\}$ in practice and since $\mathsf E(1/X|\epsilon\leq |X|)$ exists, our sample mean is well behaved. But why should the sample mean converge to $(1)$ in this case?

Edit:

From my previous question we can further define the higher order moments $\mathsf E(1/X^m)$ for $m\in\Bbb N$ with the use of a generating function via: $$ \tag{2} \mathsf E(1/X^m):=\frac{\sqrt 2}{\sigma (m-1)!}\partial_t^{m-1}\mathcal D\left(\frac{\mu-t}{\sqrt 2 \sigma}\right)\bigg|_{t=0}. $$ As before, the sample moments $(\overline{1/X^m})_n=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{k=1}^nX_k^{-m}$ will agree with the "regularized" moments $(2)$ whenever $|\sigma/\mu|$ is small. But why?