The formal statement

Writing $$

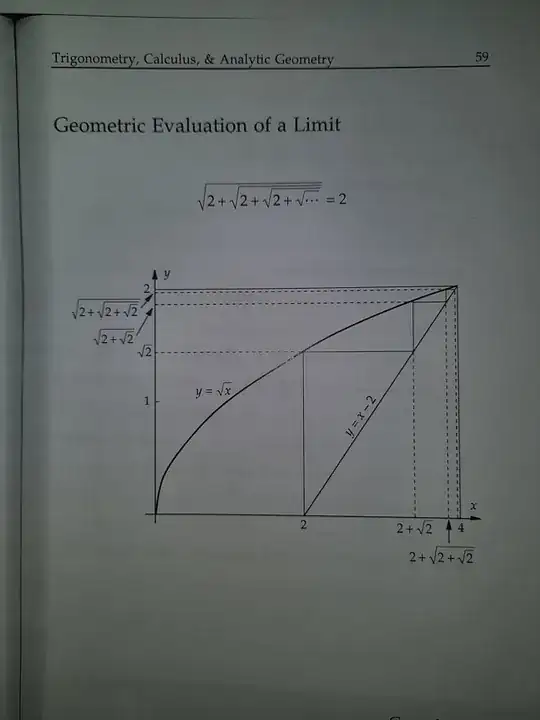

\sqrt{2+\sqrt{2+\sqrt{2+\sqrt{2+\ldots}}}} = 2

$$

may be correct, but it's not rigorous because the LHS needs more care in definition. What seems to be proved using the image, is the following :

Let $x_1 = \sqrt{2}$, and $x_{i+1} = \sqrt{2+x_i}$ for $i \geq 1$. Then, $x_i \to 2$ (as $i \to \infty$).

We can try to interpret how the diagram proves this statement.

Understanding the points on the diagram + notation

Recall that the "ordinate" of a point on the plane is its $y$-coordinate, and the "abscissa" of a point on the plane is its $x$-coordinate.

The idea of interpreting the proof is to find the $x_i$ as the ordinates of appropriate points on the curve $y = \sqrt{x}$.

Of course, $x_1 = \sqrt 2$ is the ordinate of the point $(2,\sqrt{2})$. Let us use $A_i := (x_i^2,x_i)$ to denote the sequence of points whose ordinates are $x_i$. Naturally, all the $A_i$ lie on the curve $y = \sqrt{x}$.

Now, how do we move from $A_{i}$ to $A_{i+1}$? We have $x_{i+1}^2 = 2+x_i$, and therefore, $x_{i+1}^2 - 2 = x_i$. In other words, the abscissa of $A_{i+1}$ is $2$ more than the ordinate of $A_i$. That is, the point whose abscissa is that of $A_{i+1}$ and whose ordinate is that of $A_i$ (a point called as $B_i$ later on) lies on the line $x-2 = y$.

This tells us how to go from $A_{i}$ to $A_{i+1}$ geometrically :

Find the point on $x-2=y$ with the same ordinate as $A_i$. If $A_i = (x_i^2,x_i)$, this will take you to the point $B_i := (x_i+2,x_i)$.

Find the point on $y=\sqrt{x}$ with the same abscissa as $B_i$. If $B_i = (x_i+2, x_i)$, then this will take you to $A_{i+1} = (x_i+2, \sqrt{x_i+2})$, as desired.

Therefore, we have obtained the $A_i$ and $B_i$ as desired. We have also explained why the line $y = x-2$ appears here.

However, there are still some important things to be explained.

What we need to prove, and how the diagram hides a lot of small things

Now, what we need to prove is that $x_i \to 2$. Since the $x_i$ are the ordinates of the points $A_i$, we need to prove that the ordinates of $A_i$ go to $2$. To do this, some observations from the diagram have to be made rigorous.

Why do all the points $A_i$ and $B_i$ lie in the rectangle $[0,4] \times [0,2]$?

Why does every $B_i$ lie strictly to the right of $A_i$, and every $A_{i+1}$ lie strictly above $B_i$?

We need to answer each of these questions using the appropriate analytic tools. That is not going to be revealed by the picture.

Why do all the points $A_i$ and $B_i$ lie in the rectangle $R := [0,4] \times [0,2]$?

Clearly, $A_0 \in R$. From here, one proves two things : if $A_i \in R$, then $B_i \in R$, and if $B_i \in R$ then $A_{i+1} \in R$ for all $i$. If each is proved, then by induction all the $A_i,B_i \in R$.

Now, if $A_i = (x_i^2,x_i) \in R$ then $0 \leq x_i \leq 2$. This implies that $0\leq x_i+2 \leq 4$, so obviously $B_i = (x_i+2,x_i) \in R$.

On the other hand, if $B_i = (x_i+2,x_i)\in R$, then $0 \leq x_i+2 \leq 4$, so $0 \leq \sqrt{x_i+2} \leq 4$. This implies that $A_{i+1} = (x_i+2, \sqrt{x_i+2}) \in R$.

Therefore, both sequences of points lie within $R$.

Why does every $B_i$ lie strictly to the right of $A_i$, and every $A_{i+1}$ lie strictly above $B_i$?

The movement from $A_i$ to $B_{i}$ is a movement of the abscissa from $x_i^2$ to $x_i+2$. One can check that $t^2 \leq t+2$ for $-1 \leq t \leq 2$. Indeed, note that $t^2-t-2 = (t-2)(t+1)$ which is strictly negative for $-1 < t < 2$. Therefore, $B_i$ is always strictly to the right of $A_i$.

The movement from $B_{i}$ to $A_{i+1}$ is a movement of the ordinate from $x_i$ to $\sqrt{x_i+2}$. Using the same argument as above, $t \leq \sqrt{t+2}$ for $-1<t<2$. Therefore, $A_{i+1}$ is always strictly above $B_i$.

Proving the limit

Remarkably, the two facts above are geometrically enough to explain why the $A_i$ and $B_i$ converge : and to the same point.

Why $A_i,B_i$ converge to the same point : geometrically and analytically.

To explain this geometrically, note that $A_{i+1}$ lies vertically and to the right of $A_i$, and $B_{i+1}$ also lies vertically and to the right of $B_i$ for each $i$. However, we also know that all the $A_i$ and $B_i$ lie within the rectangle $R$. Therefore, as $i$ progresses, the points $A_i$ and $B_i$ are actually getting compressed into smaller and smaller sub rectangles and are therefore getting closer and closer to some limit. This happens for both the $A_i$ and for the $B_i$.

To be precise : the ordinates and abscissa of the $A_i$ are monotone increasing sequences (which follows from the fact that $A_{i+1}$ is always to the top right of $A_i$) which are bounded (because $A_i \in R$ for all $i$ and $R$ is bounded) and therefore converge : so $A_i$ converges. The same applies with $B_i$.

However, the $A_i$ and $B_i$ converge to the same point! To prove this, go back to the construction : we construct $A_{i+1}$ from $A_i$ by first going from $A_{i}$ to $B_i$, and then from $B_{i}$ to $A_{i+1}$. In this process, if you look at the triangle formed by the points $A_i,B_i,A_{i+1}$, then it's right-angled at $B_i$, so the hypotenuse (which is the longest side of the triangle) is the line connecting $A_i$ and $A_{i+1}$, which must be longer than the line joining $A_i$ and $B_i$ which is one of the sides of that triangle. Therefore, as the $A_i$ get closer to each other, the $A_i$ are also forced to get closer to the $B_i$.

To put this mathematically, $d(A_i, B_i) < d(A_{i}, A_{i+1})$ for all $i$ by the construction of $A_i$ and $B_i$, where $d$ denotes the (Euclidean) distance between the points. Since $A_i$ is a convergent sequence, we know that $d(A_i,A_{i+1})$ goes to $0$ (i.e. it is also a Cauchy sequence). However, this forces $d(A_i,B_i) \to 0$ and therefore , $A_i$ and $B_i$ share the same limit.

What is the limit?

So, what is that limit? Since the $A_i$s lie on the curve $y=\sqrt{x}$ and the $B_i$s lie on the curve $y = x-2$, their limits continue to lie on those curves respectively. However , the limits of both $A_i$ and $B_i$ are the same! Then it must be an intersection point of the two curves.

To make this rigorous : suppose that $A_i$ converges to a limit $A$. The $A_i$s lie on the curve $y = \sqrt{x}$. Now, $y = \sqrt{x}$ is a closed subset of $\mathbb R^2$ because it's equal to $f^{-1}(\{0\})$ where $f(x,y) = x^2-y$ on $[0,\infty) \times \mathbb R$. Therefore, $A$ continues to lie on the curve $y = \sqrt{x}$. An analogous argument tells you that the limit $B$ of $B_i$ will lie on $y = x-2$. However, $A=B$, hence the intersection assertion follows.

So where do $y = x-2$ and $y = \sqrt{x}$ intersect? Using simple algebra, this happens when $\sqrt{x} = x-2$ i.e. when $x = x^2-4x+4$. This simplifies to $x^2-5x+4 = 0$ which gives $(x-1)(x-4) = 0$. Therefore, $x=1$ or $x=4$. However, note that $x=1$ is impossible since any point with an abscissa of $1$ must be to the left of $A_1$, which is not possible by their construction. Therefore, $x=4$ and $y=2$.

The intersection point is $(4,2)$. Thus, by the remark made in the start of section $2$, the ordinate $2$ is the limit of the ordinates of $A_i$ i.e. $x_i \to 2$.

Summary

Geometrically :

The points $A_i$ are constructed by having $A_1 = (2,\sqrt 2)$ and $A_{i+1}$ constructed as follows : begin from $A_i$, travel horizontally till you hit the line $x = y-2$, then travel vertically till you hit the curve $y = \sqrt{x}$. That point is $A_{i+1}$.

The points $A_{i},B_i$ thus constructed all lie in the rectangle $R = [0,4] \times [0,2]$. Furthermore, for all $i$, $A_{i+1}$ is to the top right of $A_i$ and $B_{i+1}$ is to the top right of $B_i$.

By the boundedness of $R$ and the above monotonicity property, the points $A_i$ and $B_i$ converge. Furthermore, they converge to the same point by the construction made. That limit must be the intersection of the graphs.

Analytically :

Define $A_1 = (2,\sqrt 2)$ and for $A_i = (x_i^2,x_i)$ define $B_i = (x_i+2,x_i)$ and $A_{i+1} = (x_i+2,\sqrt{x_i+2})$.

For all $i$, we have $A_{i}, B_{i} \in [0,4] \times [0,2]$. Furthermore, for each $i$, the abscissa and ordinate of $A_{i+1}$ exceed that of $A_i$, and the abscissa and ordinate of $B_{i+1}$ exceed that of $B_i$.

By the boundedness of $R$ , the sequence of abscissas and ordinates of each of the $A_i$ and $B_i$ all converge i.e. $A_i,B_i$ converge as points in $\mathbb R^2$. Furthermore, since $d(A_i,B_i) < d(A_i,A_{i+1})$ for all $i$, they converge to the same point. Since the sets $y = \sqrt{x}$ and $y = x-2$ are closed, the two sequences converge to the same point which must be an intersection point of the curves. Finally, that intersection point is $(4,2)$ whose ordinate is $2$, revealing that $2 = \lim_{i \to \infty} x_i$, as desired.