This is inspired by the inequality $g^n > g^{n-2} + \cdots + 1$ in Conrad's excellent answer.

Let $g = \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}$ as in his answer. Consider the polynomial

$$Q(x) = (x-a_{n-1})P(x) = x^{n+1} + \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} b_k x^k

$$

where $b_k = \begin{cases} a_{k-1} - a_{n-1} a_k & k > 0\\-a_{n-1}a_0, &k = 0\end{cases}$.

Since all $a_k \in [0,1]$, all $|b_k| \le 1$. For $z \in \mathbb{C}$ with $|z| = g$, we have

$$\left|\sum_{k=0}^{n-1} b_k z^k \right|

\le \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} g^k = \frac{g^n - 1}{g-1} < \frac{g^n}{g-1} = g^{n+1} = |z^{n+1}|$$

By Rouché's theorem,

all roots of $Q(z)$ and hence all roots of $P(z)$ belongs to the open disc $|z| < g$.

As a result, all roots of $P(z)$ have $\Re z < g$.

Update - an improved upper bound $\Re(z) \le u_* \sim 1.214497857615758$.

Let $z$ be any root of $P(x)$ outside unit disc (ie. $|z| > 1$). Let

$$c_k = \begin{cases}a_{n-k}, & 1 \le k \le n\\ 0, & k > n\end{cases}

\quad\text{ and }\quad \epsilon = 2c_k - 1\quad\text{ for all } k

$$

Since all $c_k \in [0,1]$, all $|\epsilon_k| \le 1$. Using the fact $P(z)= 0$, we have

$$0 = \frac{2}{z^n}P(z) = 2 + \sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{2c_k}{z^k}

= 2 + \sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1+\epsilon_k}{z^k}

= \frac{2z - 1}{z-1} + \sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{\epsilon_k}{z^k}

$$

This leads to

$$\left|\frac{2z-1}{z-1} \right| = \left|\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{\epsilon_k}{z^k} \right| \le \sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{|z|^k} =

\frac{1}{|z|-1}

$$

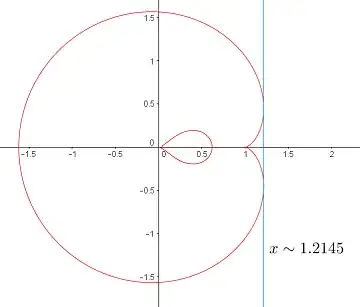

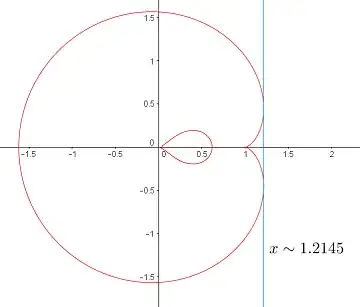

This implies all roots of $P(x)$ lies inside a region "bounded" by the curve

$$|z| = 1 + \left|\frac{z-1}{2z-1}\right|$$

Expand $z$ as $u + iv$ and using a CAS, we find this curve is part of an octic curve (the outer portion of the red curve in the illustration below):

$$4v^8+16u^2v^6-8uv^6-8v^6+24u^4v^4-24u^3v^4-20u^2v^4+20uv^4-4v^4+16u^6v^2-24u^5v^2-16u^4v^2+40u^3v^2-20u^2v^2+4uv^2-v^2+4u^8-8u^7-

4u^6+20u^5-16u^4+4u^3 = 0$$

As one can see, the $u$ in this curve doesn't reach $g$. Instead, it lies inside a half-plane $\Re z \le u_*$ for some $u_* \sim 1.2$. With help of a CAS again, we find $u_*$ is a root of the heptic polynomial

$$2048u^7-19456u^6+52608u^5-62848u^4+36752u^3-10288u^2+1392u-171 = 0$$

with a more accurate estimate $u_* \sim 1.214497857615758$.