Before we begin, a few definitions are in order. Assume we have a simple $n$-gon $P$ with a set of vertices $\{v_1, v_2, v_3,...,v_n\}$ where $v_k$ and $v_{k+1}$ are connected by an edge, as well as $v_n$ and $v_1$.

Definition 1: A vertex $v_k$ is called an ear if the line segment connecting $v_{k-1}$ and $v_{k+1}$ falls entirely within the interior of $P$.

Definition 2: A vertex $v_k$ is called a mouth if the line segment connecting $v_{k-1}$ and $v_{k+1}$ falls entitely within the exterior of $P$.

Definition 3: $P$ is called an anthropomorphic polygon if it has exactly two ears and one mouth.

Definition 4: $P$ is called a municipal polygon if it has exactly $2p$ ears and $p$ mouths for $p\in\mathbb{N}$. $p$ is called the order of $P$.

I will concede that, while anthropomorphic polygons are a real, recognized term (see this article by Godfried Toussant), "municipal polygons" is a name I came up with. I apologize if this class of polygon has an established name that I am not using, but I have been unable to find anything on them.

We can associate every municipal polygon with a word comprised of $I$'s and $O$'s by starting at some vertex and working clockwise around the polygon. We can define some function $f(v_k)$ such that $f(v_k)=I$ if $m\angle v_k<180^\circ$ and $f(v_k)=O$ if $m\angle v_k>180^\circ$. We can then apply this function to each vertex, concatenate the outputs, and say that that word is associated with the polygon $P$. After some thinking, it becomes apparent that the word associated with a municipal polygon of order $p$ must contain at least $2p\ I$'s and $p\ O$'s.

Definition 5: Two polygons are isomorphic if their associated words come from the same shape.

We can break the class of municipal polygons down further with the following definition:

Definition 6: A municipal polygon is called perfect if it is a $3p$-gon of order $p$, and imperfect if it is an $m$-gon where $m>3p$.

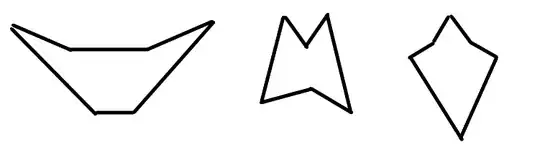

To the best of my knowledge, there are exactly three non-isomorphic perfect municipal hexagons, seen below, each with 4 ears and 2 mouths. These are associated with the words $OOIIII$, $OIIOII$, and $OIOIII$, from left to right.

Theorem: There can be no more than ${3p \choose p}-2$ perfect municipal $3p$-gons.

The proof of this theorem is simple. A perfect municipal $3p$-gon will have an associated word made up of $2p\ I$'s and $p\ O$'s. Therefore, there are ${3p \choose p}$ different words. However, some of these words will refer to the same shape: for example, $OOIIII$ and $IOOIII$ are both valid ways to refer to the leftmost shape in the above diagram. We can always chose one word to be the "canonical" form of the polygon and then disregard any versions of it "shifted over" by one or two.

The reason I cut off the upper bound so short is due to the fact that we could have a word that is $p$ copies of $OII$ concatenated together. If this is the word we had chosen, then we can at least rule out $IIO...IIO$ and $IOI...IOI$ safely.

Here are my questions:

- How many non-isomorphic perfect municipal polygons of order $p$ exist? I have my upper bound, but even at $p=2$, the upper bound (eight) is far above the real result (three). I know it can be brought down more, I just don't know how.

- Does every word with $2p\ I$'s and $p\ O$'s correspond to a perfect municipal polygon? It is entirely possible that we have vertices that are neither ears nor mouths, after all, and even if they all are, there is no guarantee that there will still be $2p$ ears and $p$ mouths.

- How many non-isomorphic municipal polygons of order $p$ exist in general? I anticipate this to be a much more difficult question, and I would not be surprised if there were an infinite supply of them. For example, in the article linked above, the author provides an example of an anthropomorphic polygon that happens to be a 17-gon. I imagine that one could easily find egregious examples akin to this for municipal polygons as well.

Any and all help would be appreciated. Thank you!