I'm learning about Fourier transforms and watching this video.

Let's look at these examples:

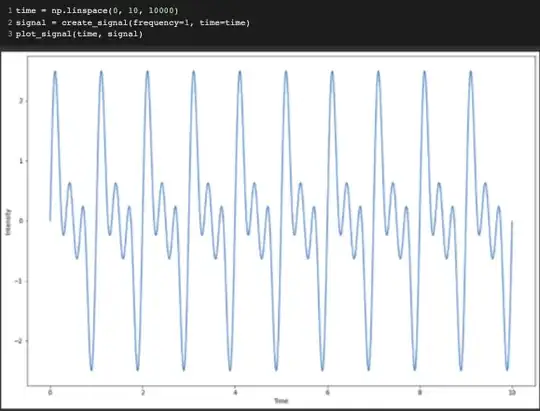

This is our signal with a frequency of 1

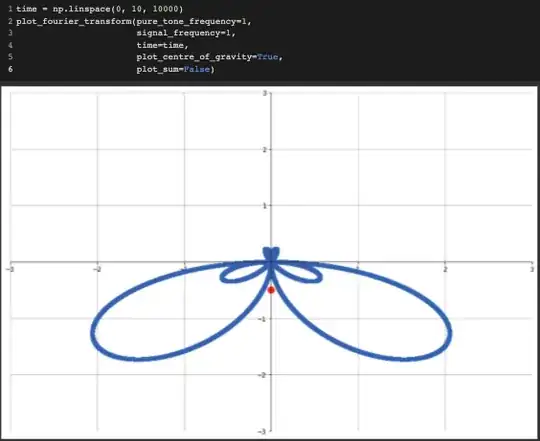

This is the Fourier transform for frequency 1 (which is in the sound):

As we can see, the centre of gravity(the average of all points)is a non-zero value.

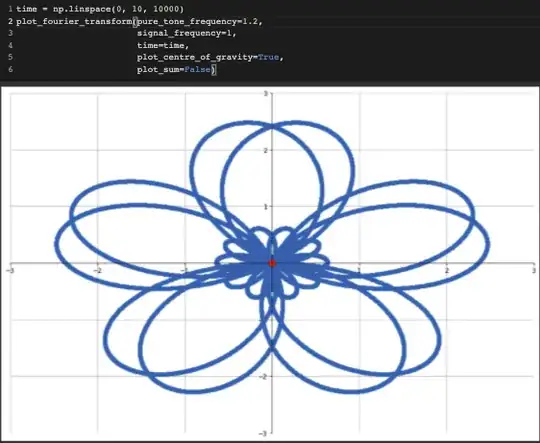

But for a frequency not in the sound (for example, 1.2), we get a symmetric shape, and the average of all points become zero.

The formula for calculating the coefficient is this: $ \huge{ \hat{g}(t) = \int {g(t) e^{-i2\pi ft}} dt} $

Where f is the frequency, we're checking, and t is time.

Why do we get a symmetric shape for the frequencies not in the sound (therefore a zero centre of gravity) and a non-symmetric shape for frequencies based on this formula?

$\e^0in the integral which gives us t and for the second one we get$\e^i(f'-f)*2*pi*t! – Morez Jan 01 '22 at 18:430for the first one – Morez Jan 01 '22 at 18:45