When I read user21820's answer I was somewhat confused because it seemed to contradict what I believed to be "well-known" about the Peano axioms. But he is right, and my answer tries to explain the problem from my (perhaps naive) point of view.

I do not want to go down to the foundations of set theory, but one should be aware that set theory is based on certain axioms. A frequently used approach is ZF (= Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory).

In my opinion a nice introduction to set theory is

Halmos, Paul R. Naive set theory. Courier Dover Publications, 2017.

The first four Peano axioms say that we consider a "successor system" $(N,0,S)$ where $N$ is a set, $0\in N$ and $S : N \to N$ is an injective function such that $0 \notin S(N)$. In such a system $N$ cannot be finite. The existence of an infinite set is assured by ZF, and using the machine of set theory we can construct quite a number of distinct models of successor systems. In particular we can construct the natural numbers $\mathbb N$ as we "naively" know them; see e.g. Halmos ($0$ and $S$ are inherent in this construction). Let us call it the standard model.

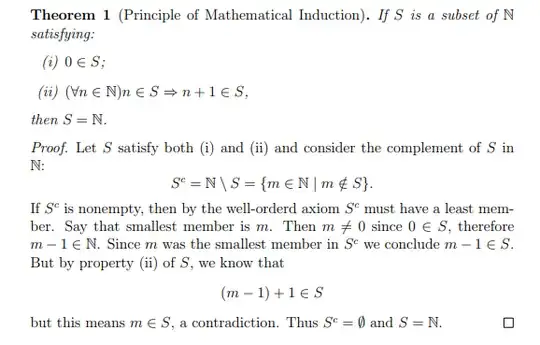

Let us now consider successor systems satisfying the Induction Axiom. The standard model satisfies the Induction Axiom, and this shows that the existence of a system satisfying all Peano axioms. It is easy to see that all such systems $(N,0,S), (N',0',S')$ are essentially identical which means that that there exists a unique bijection $b : N \to N'$ such that $b(0) = 0'$ and $S' \circ b = b \circ S$.

Using induction we can extend the successor function $S$ to an addition $A : N \times N \to N$ making $N$ a commutative semigroup with $0$ as neutral element. Based on addition we can introduce an ordering on $N$ by defining $n \le m$ if $n + k = m$ for some $k \in N$. It turns out that $(N,\le)$ is a well-ordered set (proof via induction).

But what happens if we consider an arbitrary successor system $(N,0,S)$ without assuming the induction axiom? In that case we can neither define an addition not an ordering. That is, it does not make sense to say that $N$ is well-ordered. This can only be done if we introduce an ordering $\le$ on $N$ as an additional ingredient. In other words, we have to consider systems $(N,0,S,\le)$ - and then certainly need axioms to describe the relation between $S$ and $\le$. We could for example require that $n < m$ implies $S(n) < S(m)$. In that case let us call $(N,0,S,\le)$ an "ordered successor system".

We can now show that if an ordered successor system $(N,0,S,\le)$ satisfies the Induction axiom, then $(N,\le)$ is well-ordered. However, the converse is not true (see Math's answer). It can be repaired by adding Paul Frost's axiom. But be aware that we are no longer working with successor systems $(N,0,S)$, we need an ordering $\le$ as part of the structure.

Moreover, if we consider an arbitrary ordered successor system $(N,0,S,\le)$, we still cannot define an addition on $N$. We can bypass this by appending an addition $+$ to $(N,0,S,\le)$, i.e. by considering systems $(N,0,S,\le,+)$. Of course we need suitable axioms to decribe the relations between $S, \le$ and $+$. This is the purpose of PA$^-$ in user21820's answer.