This equation asks for the roots of a rational function in unknown variable $\Omega$:

$$ -\frac{1}{\alpha} = \sum_{r=1}^{m} \frac{v_r^2}{\omega_r^2-\Omega} $$

where we assume for the sake of definiteness that $\alpha \gt 0$, and also that the $v_r \gt 0$ and $\omega_r$ are distinct and nonnegative (otherwise rewriting the equation will assure this):

$$ 0 \le \omega_1 \lt \omega_2 \lt \ldots \lt \omega_m $$

With basic algebra it can be converted to a polynomial equation of degree $m$, so there are at most $m$ roots. In fact we can deduce the locations (intervals) of exactly $m$ real roots from the rational form of the equation.

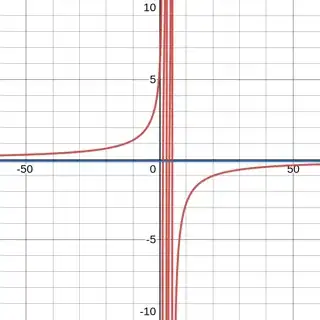

The right hand side expression has discontinuities (simple poles) at the arguments $\Omega = \omega_r^2$ where each respective term goes from $+\infty$ to $-\infty$ as $\Omega$ increases past that singularity.

Note that for $\Omega < \omega_1^2$ all the terms on the right hand side are strictly positive, while the left hand side is strictly negative. Therefore there are no solutions of the equation in the interval $(-\infty,\omega_1^2)$.

At the other extreme, as $\Omega \to +\infty$ the right hand side tends to zero from below because when $\Omega \gt \omega_m^2$ all the terms there are negative (but grow increasingly tiny). On the other hand, as $\Omega$ approaches $\omega_m^2$ from above, the right hand side as a whole approaches $-\infty$. Therefore, by the Intermediate Value Theorem, the interval $(\omega_m^2,+\infty)$ contains a root, and because the expression on the right hand side is (strictly) monotone increasing there (as negative values), that root is unique in that interval.

Similarly each of the intervals $(\omega_r^2,\omega_{r+1}^2)$ between "fence posts" $\omega_r, 1 \le r \lt m$ will contain a root because the right hand side expression continuously swings from arbitrarily large negative values just above $\omega_r$ to arbitrarily large positive values just below $\omega_{r+1}$.

This accounts for the locations of the maximum possible number of roots, at least in the case that (as assumed above) $\alpha \gt 0$ (so that the left hand side of the equation is negative). If we instead ask for $\alpha \lt 0$, this would remove the root from $(\omega_m^2,+\infty)$ and introduce a new root in $(-\infty,\omega_1^2)$.

Here is a (Desmos prepared) graph that illustrates the rational curve crossing the line $y=-0.1$ corresponding to the example at the end of the Question:

In any case once the roots are suitably isolated in this fashion, it is pretty easy to obtain accurate numerical approximations. Robust methods like bisection and regula falsi can sharpen the initial approximations to a region where Newton's method etc. begin rapid convergence as necessary.