Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications, 7th edition, Global Edition, Kenneth Rosen, Kamala Krithivasan is the textbook I am referencing here.

I am trying to learn how to do mathematical induction.

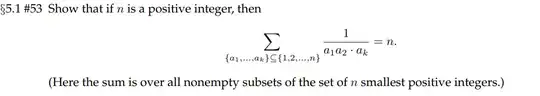

However, I can't help but be confused at how I would go about with substituting in P(k) and P(k+1) so that I can prove these are equal to n?

Like how would that work out to if k and k+1 are subbed in and how do I go about with simplifying the P(k+1) expression such that it proves that P(k+1) holds?

$$P(k): \ \ \ \ \sum _{\{a_1,...,a_i\}\subset\{1,2,...,k\}}\dfrac{1}{a_1.a_2...a_i}=k \tag{1}$$

I have proven that P(1) is true as 1 ⊆ 1, in summation is 1 which is n. So P(1) holds.

Not sure how I should go about with finding/proving P(k) and P(k+1) and how would it look in working?

Any help is appreciated, thank you! :)