I came across this question during my course on Discrete Math, while we were discussing the pigeonhole principle:

We are given $n$ coins each of weight $0$ or $1$. We are given a scale using which we can weigh an arbitrary subset of the coins. The objective is to determine the weight of each of the $n$ coins, using a minimal number of weighings. We are allowed to use information from previous weighings. For example if we know $\{1, 2\}$ weighs $1$ and $\{2, 3\}$ weighs $2$, we can conclude that coin $1$ has weight $0$. Show that you will need to weigh at least $n/\log_2(n+1)$ subsets of coins to determine the final weight.

Unfortunately, I am at a loss to solve it, and am entirely unsure on how to proceed. Here is what I have gathered:

- No matter what algorithm is given, there is a case in which it is necessary to weigh at least $n/\log_2(n+1)$ subsets.

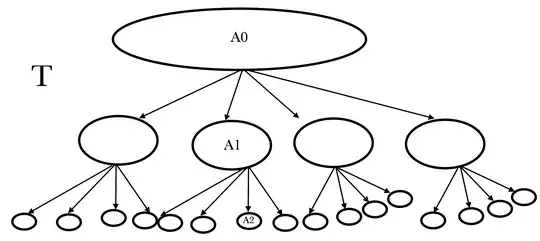

- The inequality essentially simplifies to $(n+1)^k \geq 2^n$, where $k$ is the number of weighings.

- Since we're talking about subsets and the pigeonhole principle, the number $2^n$ of subsets of $n$ coins is relevant.

Can I have a hint as to how to proceed? Is it possible that induction could be a way forward?