Let $X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n$ be i.i.d observations of a continuous random variable $X$. Let $Y_n$ be the sample variance: $$ Y_n = \bigg(n\sum_{i=1}^n X_i^2 - \bigg(\sum_{i=1}^nX_i \bigg)^2\bigg)^k. $$ Actually, for $k=1$, $Y_n$ is simply the sample variance scaled by $n^2$, i.e., we can write it as $$ Y_n = n^2 \bigg(\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n X_i^2 - \bigg(\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nX_i \bigg)^2\bigg). $$

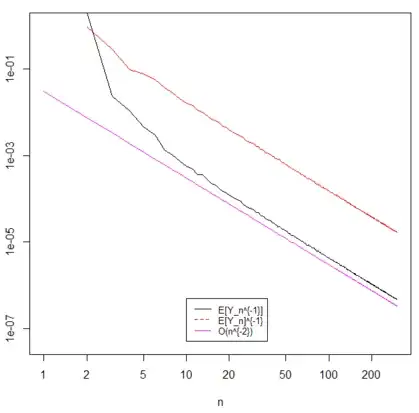

Here is a plot for the case of $k=1$.

From running computational simulations it is clear that $E[Y_n^{-1}]$ and $E[Y_n]^{-1}$ converge at the same rate as $n \to \infty$, e.g. there exists constants $C_1$ and $C_2$ such that $$ C_1 E[Y_n]^{-1} \le E[Y_n^{-1}] \le C_2 E[Y_n]^{-1}, $$ for some constant $C$. In fact the simulations show they both converge as $O(n^{-2k})$. But how can we prove they have the same rate of convergence?