The title of this post is intentionally sensational, but what I am really going to do is to compare the divergent integrals $\int_0^1\frac1xdx$ and $\int_1^\infty\frac1xdx$.

Let's consider the transform $\mathcal{L}_t[t f(t)](x)$. It is notable by the fact that it preserves the area under the curve: $$\int_0^\infty f(x)dx=\int_0^\infty \mathcal{L}_t[t f(t)](x) dx$$

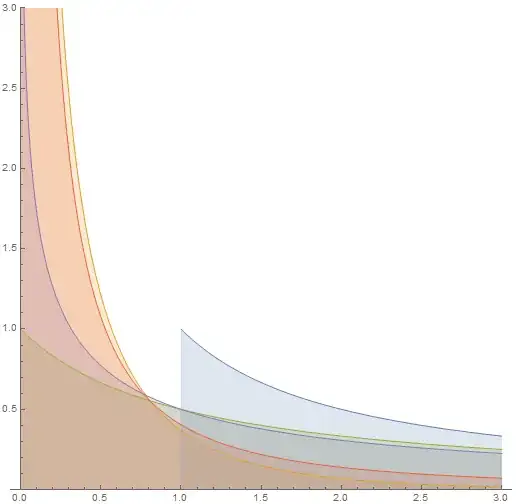

But more interesting, it also works well with divergent integrals, allowing us to define the equivalence classes of divergent integrals. Particularly, by successfully applying this transform to $\int_1^\infty \frac1xdx=\int_0^\infty\frac{\theta (x-1)}{x}dx$, one can obtain the following equivalence class of divergent integrals (the first one and the third one turn out to be similar up to a shift):

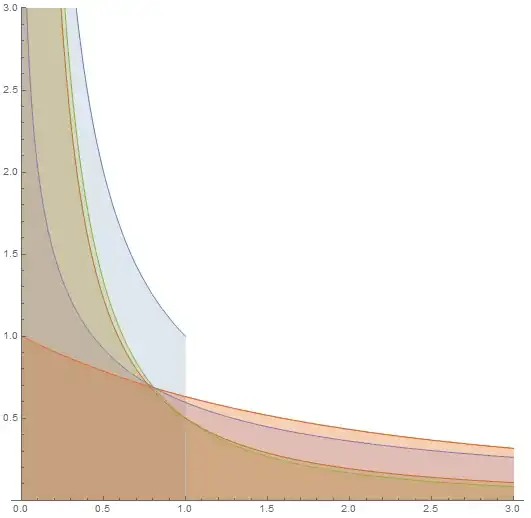

$\int_0^\infty\frac{\theta (x-1)}{x}dx=\int_0^\infty\frac{e^{-x}}{x}dx=\int_0^\infty\frac{dx}{x+1}=\int_0^\infty\frac{e^x x \text{Ei}(-x)+1}{x}dx=\int_0^\infty\frac{x-\ln x-1}{(x-1)^2}dx$

On the other hand, applying the transform to $\int_0^1\frac1x dx=\int_0^\infty \frac{\theta (1-x)}{x}dx$ one can obtain another set of equal integrals:

$\int_0^\infty\frac{\theta (1-x)}{x}dx=\int_0^\infty\frac{1-e^{-x}}{x}dx=\int_0^\infty\frac{1}{x^2+x}dx=\int_0^\infty-e^x \text{Ei}(-x)dx=\int_0^\infty-\frac{x-x\ln x-1}{(x-1)^2 x}dx$

Now, having postulated equivalence of divergent integrals in each class, we can pick two integrals, one from each class and compare them. Well, it seems, the integrals in the second class are bigger by an Euler's constant:

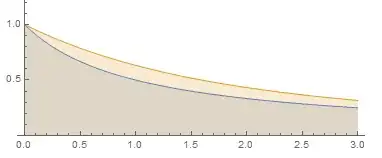

$\int_0^{\infty } \left(\frac{1-e^{-x}}{x}-\frac{1}{x+1}\right) \, dx=\gamma$

And thus, we can conclude that $\int_0^1\frac1xdx=\gamma+\int_1^\infty \frac1xdx$. Surprising, is not it, given that one would naively expect $\ln 0=-\ln\infty$?

But we also have an identity $\gamma = \lim_{n\to\infty}\left(\sum_{k=1}^n \frac1{k}-\int_1^n\frac1t dt\right)$ and know the regularized value of harmonic series $\operatorname{reg}\sum_{k=1}^n \frac1{k}=\gamma$. Thus, we obtain $$\int_0^1\frac1xdx=\gamma+\int_1^\infty\frac1xdx=\sum_{k=1}^\infty\frac1k.$$

So, the integrals differ by Euler-Mascheroni constant. Is there any logical explanation for this?