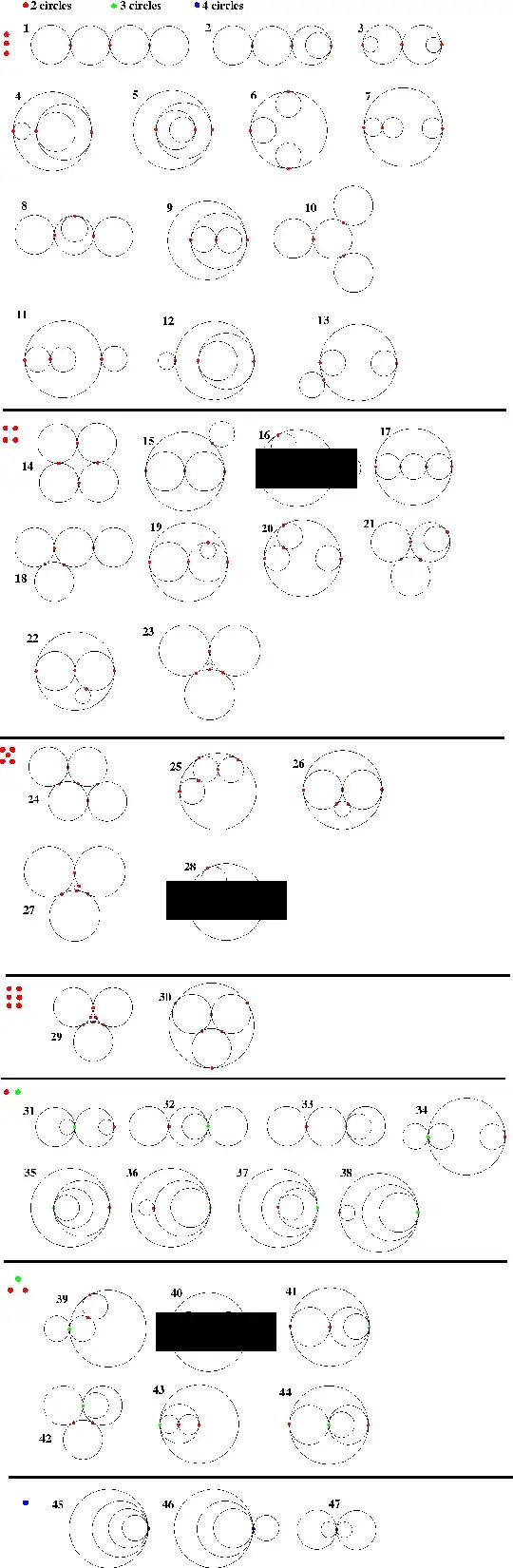

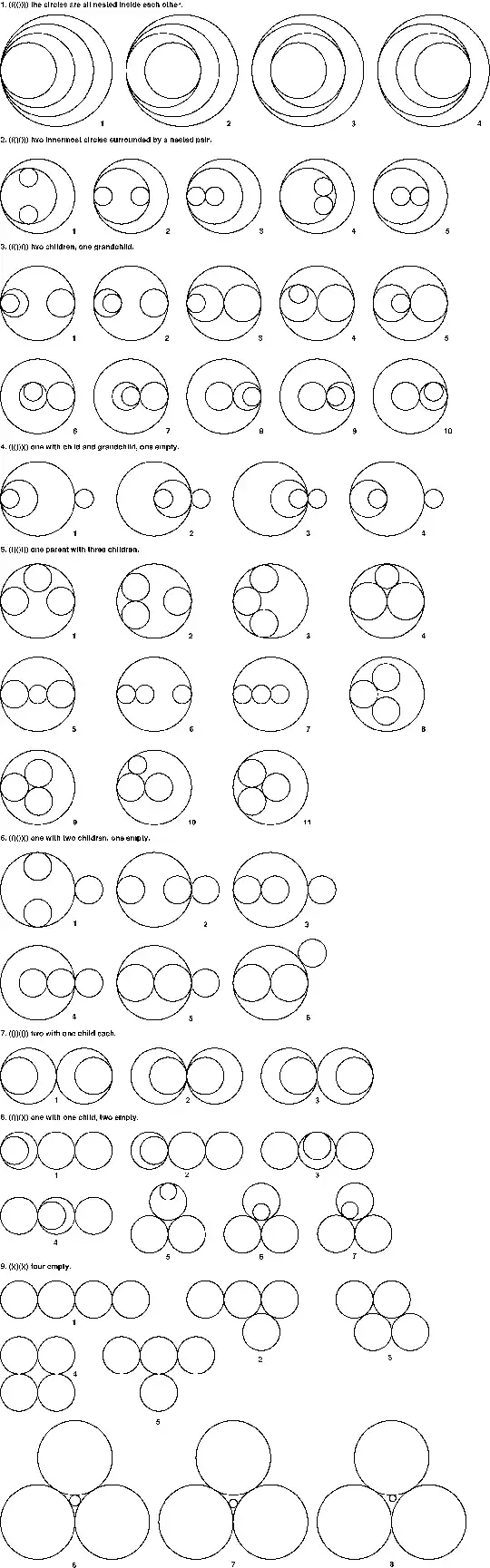

Let's be a little systemic about drawing these.

For $n=4$, there are 9 hierarchies of circles (I think this is from OEIS A000081).

(((()))) the circles are all nested inside each other.

There are four of these: the differences come from whether the points of tangency coincide or not. You have them labelled as #26, #28, #29, and #30 in the diagram when I started writing this.

((()())) two innermost circles surrounded by a nested pair.

There are six of these: the two innermost circles can either 1. each touch only their parent, 2. touch each other but only one touch the parent, or 3. touch each other and both touch the parent, and then the point of tangency with the grandparent can be involved or not. Of these, only one is included in your diagram, as #34.

((())()) two children, one grandchild.

I'll call the child with its own child A, and the child without its own child B. The children can touch just the parent (and the grandchild can touch or not the outer circle); A can touch only B and not parent (and the grandchild can touch or not B); B can touch only A and not parent (and the grandchild can touch B, the outer circle, or neither); A and B can touch both each other and the parent (and the grandchild can touch B, the outer circle, or neither), for a total of 10. Of these, you have five: #22, #23, #31, #32, and #33.

((()))() one with child and grandchild, one empty.

There are four of these: the grandchild can touch or not the grandparent, and the child can touch or not its uncle. Of these you have two, #27 and #45.

(()()()) one parent with three children.

The three children can be in four layouts: they can not touch at all; there can be one pair and one lonely one; there can be three in a line; there can be all three in a triangle. This leads to eleven in the whole class: the three independent siblings can all touch parent #16, the pair can both touch #13 or only one can #35, the line can touch once on the end or in the middle (you have neither) or twice on both ends #12 or end and middle #25 or three times #19, the triangle can touch once (not present) twice (double counted #15 and #24) or three times (#11)

(()())() one with two children, one empty.

This lineup is basically the same as type 2; the only difference is that the "outermost circle" in 2 has become an uncle instead of a grandparent. You have five of these #14 #17 #18 #39 #43, and have double counted two as #20 and #21 - you're missing the uncle-tangent counterpart to #14.

(())(()) two with one child each.

There's only three of these: the question is how many children touch their uncles. It could be zero #38, one #37, or two #36.

(())()() one with one child, two empty.

Geometry finally comes into play! The three outer circles can be in a line or triangle. If they're in a line, the child can be in one of the ends, or in the middle, and it can touch or not an uncle #6, #7, #8, #44; if they're in a triangle, the child can touch one of the uncles #10, or outside the triangle formed by the uncles #9, or inside that triangle (not present)

()()()() four empties.

I think you actually have all of these: there's line #5, triangle plus tail #1, rhombus #2, square #3, star #40, and then there are three that are a triangle with circle in the middle that touches one #42 two #41 or three #4 of the outer circles.

So in total you appear to have (in the diagram when I started writing this answer double counted three (#20 is the same as #18, #21 is the same as #17, and #24 is the same as #15), and missed sixteen, for a grand total of 58 that I can count.