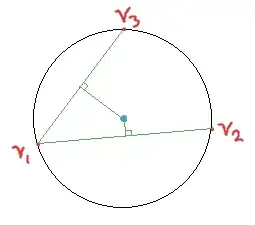

Given $m$ points $v_i\in\mathbb{R}^n$, $m<n$. How to find the circumcenter of the simplex formed by the points?

-

Assuming $v_i$ in general position. You do it inductively starting with 2 being the mid-point and successively add new point and orthogonal directions. – user10354138 Mar 10 '21 at 09:02

-

@user10354138 Do you mean finding the intersection point of orthogonals of two faces (recursively starting from the vertices)? – Nico Schlömer Mar 10 '21 at 09:10

-

No, I mean starting from one face $v_1,\dots,v_k$ and its circumcentre $c_k$, the circumcentre of $v_1,\dots,v_{k+1}$ is $c_{k+1}=c_k+\lambda u_{k+1}$ where $u_{k+1}=\operatorname{proj}{\operatorname{affinespan}{v_1,\dots,v_k}^\perp}(v{k+1}-v_1)$ is new orthogonal direction that you need to take care of. – user10354138 Mar 10 '21 at 09:16

-

That's alright, but how to find $\lambda$? (Intersection with the same orthogonal stepping from another face came to mind.) – Nico Schlömer Mar 10 '21 at 09:18

-

You find it by solving a quadratic (actually only linear) equation $(v_1-c_{k+1})^2=(v_{k+1}-c_{k+1})^2$. – user10354138 Mar 10 '21 at 09:19

-

The circumcenter is the intersection of the "perpendicular bisector hyperplanes" of segments determined by pairs of vertices. In particular, it's the intersection of the $m-1$ hyperplanes bisecting segments emanating from any distinguished vertex you like. (Translating that vertex to the origin can simplify things a little.) Note: The perpendicular bisector hyperplane of points with coordinate vectors $p$ and $q$ is given by $(x-\frac12(p+q))\cdot(p-q)=0$. – Blue Mar 10 '21 at 09:55

-

@user10354138 To my surprise, your suggestion led to a beautiful and efficient expression for the circumcenter coordinates. (See my second answer below.) Thanks for the suggestion! – Nico Schlömer Mar 16 '21 at 22:49

-

For etymological purposes see https://www.ics.uci.edu/~eppstein/junkyard/circumcenter.html And see https://github.com/chrisjsewell/PyGauss/blob/master/pygauss/utils.py#L20 which looks same as below and I am guessing (guessing, having dug through it) is related to the cayley menger formulation in some way. – safetyduck Mar 10 '22 at 18:41

-

@NicoSchlömer, how come you deleted your answer just now? I liked it... Was it bugged? – Alec Jacobson Mar 18 '24 at 19:56

-

@AlecJacobson Indeed. – Nico Schlömer Mar 19 '24 at 20:05

-

too bad. how so? – Alec Jacobson Mar 23 '24 at 15:16

4 Answers

In Miroslav Fiedler's lovely book Matrices and Graphs in Geometry, he shows how one can use the Cayley-Menger matrix,

$$\mathbf M=\begin{pmatrix} 0&1&1&\cdots&1\\ 1&0&d_{1,2}^2&\cdots&d_{1,n+1}^2\\ 1&d_{2,1}^2&\ddots&&\vdots\\ \vdots&\vdots&&\ddots&d_{n,n+1}^2\\ 1&d_{n+1,1}^2&\cdots&d_{n+1,n}^2&0\end{pmatrix}$$

to determine the circumsphere of an $n$-simplex determined by $n+1$ $n$-dimensional points. Here, $d_{j,k}$ signifies the distance between vertices $v_j$ and $v_k$. Using the formulae from this page, and letting $\mathbf Q=-2\mathbf M^{-1}$, the circumcenter is given by

$$\left(\frac{q_{1,2}}{q_{1,2}+\cdots+q_{1,n+2}}v_1,\cdots,\frac{q_{1,n+2}}{q_{1,2}+\cdots+q_{1,n+2}}v_{n+1}\right)$$

and the circumradius is given by $\dfrac{\sqrt{q_{11}}}{2}$. The book also discusses how to use the Cayley-Menger matrix to get the insphere. (I wrote up a Mathematica implementation of Fiedler's formulae here.)

- 76,540

-

Note that $q$ is from the "extended Grammian" matrix $\hat{Q}$ so there is an extra entry there – safetyduck Feb 23 '22 at 15:36

-

Also not that this index notation does in fact start from 1 and not zero. It is confusing when you are missing the context of the "extended" M and Q. – safetyduck Feb 23 '22 at 15:45

Another approach is to form a tall matrix $A\in\mathbb{R}^{N\times n}$, where each row contains the displacement between unique pairs of vertices and $N=\frac{m(m-1)}{2}$ and a vector $b\in\mathbb{R}^N$ where each element is the half of the corresponding difference between the squared distance of pairs of vertices from the origin. The circumcenter $x\in\mathbb{R}^n$ is simply the least squares solution to this overdetermined system. This approach has the disadvantage of evaluating more terms (a quantity that scaled quadratically witgh the number of vertices), however, it should not present singular matrix problems.

$$ \begin{pmatrix} v_2 - v_1 \\ \vdots \\ v_{m} - v_{m-1} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x_1 \\ \vdots \\ x_n \end{pmatrix}=\frac{1}{2} \begin{pmatrix} \|v_2\|^2-\|v_1\|^2\\ \vdots\\ \|v_m\|^2-\|v_{m-1}\|^2 \end{pmatrix} $$

- 163

This is expansion on Mainfred Weis's answer.

The most straightforward approach is to recognize that the circumcenter, the point equidistant to all vertices, also has the property that it will lie on all (hyper)planes which bisect each combination of vertices. That is, for all unique pairs of vertices $v_i$ and $v_j$: $$\frac{(c-v_i)\cdot(v_j-v_i)}{(v_j-v_i)\cdot(v_j-v_i)}=\frac{1}{2}$$

Next, we recognize that if we have $m$ points, we only need $m-1$ hyperplanes to fully determine the system.

We can arbitrate $\vec{v}_1$ to be the "origin", and set up the following $m-1 \times n$ matrix system, where $\vec{c}'=\vec{c}-\vec{v}_1$, the relative circumcenter, and $\vec{d}_{i,j}=\vec{v}_j-\vec{v}_i$, the difference vectors:

$$\begin{pmatrix} \vec{d}_{1,2}\\ \vdots \\ \vec{d}_{1,m} \end{pmatrix} \cdot \vec{c}'=\frac{1}{2}\begin{pmatrix} \left\| \vec{d}_{1,2} \right\|^2 \\ \vdots \\ \left\| \vec{d}_{1,m} \right\|^2 \end{pmatrix}$$

When $m \leq n$

If we are so lucky to have $n + 1$ points, then we have a square matrix, and we can solve for $\vec{c}'$ directly. However, if we have $m\leq n$, then we must recognize that our relative circumcenter can be represented as a linear combination of the difference vectors, $\vec{c}'= \begin{pmatrix} \vec{d}_{1,2} & \cdots & \vec{d}_{1,m} \end{pmatrix}\cdot\begin{pmatrix} t_{1,2}\\ \vdots\\ t_{1,m} \end{pmatrix}$, and so:

$$\begin{pmatrix} \vec{d}_{1,2}\\ \vdots \\ \vec{d}_{1,m} \end{pmatrix} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} \vec{d}_{1,2} & \cdots & \vec{d}_{1,m} \end{pmatrix}\cdot\begin{pmatrix} t_{1,2}\\ \vdots\\ t_{1,m} \end{pmatrix}=\frac{1}{2}\begin{pmatrix} \left\| \vec{d}_{1,2} \right\|^2 \\ \vdots \\ \left\| \vec{d}_{1,m} \right\|^2 \end{pmatrix}$$

Allowing you to solve for $t$ and then plugging in for $\vec{c}$

A more symmetric approach

Numerically, this probably gives one of the more accurate results. The only disappointing thing about this solution so far is that we must arbitrarily choose a vertex to be our "origin".

However, if we take a page out of projective geometry, we can recognize that we can instead place all of our vertices $\vec{v}_i$ on a projective plane by appending a perpendicular element ($(x, y, z) \rightarrow (1, x, y, z)$). We can then introduce a new vertex, $\vec{v}_0 = \vec{0}$, using $\vec{v}_0$ as the "origin", disambiguating our choice.

This works because adding a new vertex can only move the circumcenter along an axis perpendicular to the existing surface spanned by our initial vertices.

This results in the following system:

$$\begin{pmatrix} 1 & \vec{v}_1\\ \vdots & \vdots \\ 1 & \vec{v}_m \end{pmatrix} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 1 & \cdots & 1 \\ \vec{v}_1 & \cdots & \vec{v}_m \end{pmatrix}\cdot\begin{pmatrix} t_{1}\\ \vdots\\ t_{m} \end{pmatrix}=\frac{1}{2}\begin{pmatrix} \left\| \vec{v}_{1} \right\|^2 + 1 \\ \vdots \\ \left\| \vec{v}_{m} \right\|^2 + 1 \end{pmatrix}$$

The solution being: $$\begin{pmatrix} \vec{v}_1 & \cdots & \vec{v}_m \end{pmatrix}\cdot\begin{pmatrix} t_{1}\\ \vdots\\ t_{m} \end{pmatrix}$$

- 698

the center of the circum-sphere of a simplex can be trivially calculated as the solution of a sytem of linear of equations: calculate any spanning tree of the corners and take the intersection of the hyperplanes that contain the midpoints of the tree edges and are orthogonal to them.

- 225