Introduction, Part 2

This is the continuation of our answer to get some lower bounds on the probability. Please read Part 1 first to get a sense of our solution strategy.

Summary, Part 1

We studied the probability that selections from a single suit solved 1-3 equations from our list. Our results were not helpful:

Proposition 1: Any selection of $43$ cards can solve all four equations.

Proposition 2: For an $18$-card set, the probability of success is at least $0.73\%$.

For Part 2, we should also recall Observation 5.

Observation 5.

- 8 cards from a single suit are guaranteed to solve a single short equation.

- 11 cards from a single suit are guaranteed to solve both a short equation and a long equation.

- 13 cards from a single suit can solve both long equations and a short equation.

Summary, Part 2

Stretching the limits of our new-ish computer, we explored the possibilities that a pair of suits (either like-colored or opposite-colored) could solve one or two equations simultaneously. (Three equations are too much to handle.) Then we attempted to solve the full system by assigning two equations to one pair of suits,

and the other two equations to the other pair of suits. This gave much better results:

Proposition 3: Any selection of $37$ cards can solve all four equations.

Proposition 4: For an $18$-card set, the probability of success is at least $62.96\%$.

Our guess would be that the probability is still higher (given the simplicity of our restricted-solution method, and Kent Haines's comment that failure is empirically rare), but our current method cannot be pushed farther without hitting a combinatorial explosion. Hence, other methods would be needed to get better bounds on the true probability.

Investigating Two-Suit Solutions to Equations

Basic Observations

We can port over the following guarantees using our one-suit answers and the pigeonhole principle.

Single Short Equation. If we have $2 \times (8-1) + 1 = 15$ cards in two suits, we must have 8 cards in 1 suit, and hence we can solve one short equation.

By contrast, it is impossible to guarantee a solution to a short equation with 14 cards by the parity obstruction noted by user @pkr. If we take the 7 odd cards per suit (A, 3, 5, 7, 9, J, K), that is $7 \times 2 = 14$ cards in general.

Single Long Equation. If we have $2 \times (11-1) + 1 = 21$ cards in two suits, we must have 11 cards in 1 suit, and hence we can solve a single long equation.

For the case of two like-colored suits, we have the size obstruction of the style given by user @player3236: if we take our sample to be 4-K$\spadesuit$ and 5-K$\clubsuit$, we have that the left-hand side of the three-term sum is at least $4 + 5 + 5 = 14 > 13$, so there is no possible solution to the long equation. Hence, 10 + 9 = 19 cards is insufficient to guarantee success in this case, and 20 cards are necessary.

For the case of two opposite-colored suits, no obvious lower bound shows itself to us.

Two Short Equations. If we have $2 \times (10-1) + 1 = 19$ cards in two suits, we must have 10 cards in 1 suit, and hence we can solve two short equations.

The parity obstruction in this case only rules out $15$ cards (since we cannot solve both short equations with one even number).

One Short and One Long Equation. If we have $2 \times (11-1) + 1 = 21$ cards in two suits, we must have 11 cards in 1 suit, so we can solve 1 short equation and 1 long equation.

For the case of two like-colored suits, we have the size obstruction of the style given by user @player3236: if we take our sample to be 5-K from both black suits, plus one of the 4's, we have that the left-hand side of the three-term sum is at least $4 + 5 + 5 = 14 > 13$, so there is no possible solution to the long equation. Hence, 10 + 9 = 19 cards is insufficient to guarantee success in this case, and 20 cards are necessary.

For the case of two opposite-colored suits, there is no obvious obstruction beyond the 15-card lower bound for the short equation by itself.

Two Long Equations. If we have $2 \times (13-1) + 1 = 25$ cards in two suits, we must be able to solve both long equations.

For the case of two like-colored suits, the size obstruction of @player3236 holds exactly, as the 21-card selection (3-K)$\spadesuit$ with 4-K$\clubsuit$ cannot solve both long equations

No obvious obstruction exists for the opposite-colored case.

Probability Tables, Like-Colored Suits

Here we give the probability tables for selections from a two-like-suit deck (e.g., $\spadesuit, \clubsuit$) for solving the given sets of equations.

Like-Colored Suits, 1 Equation

$$

\begin{array}{c| c| c}

|T| & P(\text{1 short}) & P(\text{1 long}) \\\hline

0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 0 & 0\\

2 & 0 & 0\\

3 & \frac{300}{2600} = 11.53846\% & 0\\

4 & \frac{5934}{14950} = 39.69231\% & \frac{624}{14950} = 4.17391\%\\

5 & \frac{46578}{65780} = 70.80876\% & \frac{12056}{65780} = 18.32776\%\\

6 & \frac{205023}{230230} = 89.05138\% & \frac{93908}{230230} = 40.78878\%\\

7 & \frac{635060}{657800} = 96.54302\% & \frac{407492}{657800} = 61.94770\%\\

8 & \frac{1546979}{1562275} = 99.02092\% & \frac{1206313}{1562275} = 77.21515\%\\

9 & \frac{3116496}{3124550} = 99.74223\% & \frac{2716722}{3124550} = 86.94762\%\\

10 & \frac{5308393}{5311735} = 99.93708\% & \frac{4929877}{5311735} = 92.81105\%\\

11 & \frac{7725106}{7726160} = 99.98636\% & \frac{7433766}{7726160} = 96.21553\%\\

12 & \frac{9657466}{9657700} = 99.99758\% & \frac{9475588}{9657700} = 98.11433\%\\

13 & \frac{10400568}{10400600} = 99.99969\% & \frac{10309178}{10400600} = 99.12099\%\\

14 & \frac{9657698}{9657700} = 99.99998\% & \frac{9621228}{9657700} = 99.62235\%\\

15 & 1 & \frac{7714858}{7726160} = 99.85372\%\\

16 & 1 & \frac{5309115}{5311735} = 99.95068\%\\

17 & 1 & \frac{3124124}{3124550} = 99.98637\%\\

18 & 1 & \frac{1562232}{1562275} = 99.99725\%\\

19 & 1 & \frac{657798}{657800} = 99.99970\%\\

20 & 1 & 1\\

21 & 1 & 1\\

22 & 1 & 1\\

23 & 1 & 1\\

24 & 1 & 1\\

25 & 1 & 1\\

26 & 1 & 1\\

\end{array}

$$

Like-Colored Suits, 2 Equations

$$

\begin{array}{c| c| c| c}

|T| & P(\text{2 short}) & P(\text{1 short, 1 long}) & P(\text{2 long}) \\\hline

0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

2 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

3 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

4 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

5 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

6 & \frac{23940}{230230} = 10.39830\% & 0 & 0\\

7 & \frac{308684}{657800} = 46.92673\% & \frac{50658}{657800} = 7.70112\% & 0\\

8 & \frac{1224668}{1562275} = 78.39004\% & \frac{599283}{1562275} = 38.35964\% & \frac{30771}{1562275} = 1.96963\%\\

9 & \frac{2897768}{3124550} = 92.74193\% & \frac{2044450}{3124550} = 65.43182\% & \frac{394982}{3124550} = 12.64124\%\\

10 & \frac{5195668}{5311735} = 97.81489\% & \frac{4300803}{5311735} = 80.96795\% & \frac{1572988}{5311735} = 29.61345\%\\

11 & \frac{7679338}{7726160} = 99.39398\% & \frac{6967050}{7726160} = 90.17481\% & \frac{3631926}{7726160} = 47.00816\%\\

12 & \frac{9643138}{9657700} = 99.84922\% & \frac{9209464}{9657700} = 95.35877\% & \frac{6057076}{9657700} = 62.71758\%\\

13 & \frac{10397372}{10400600} = 99.96896\% & \frac{10195040}{10400600} = 98.02358\% & \frac{7870432}{10400600} = 75.67287\%\\

14 & \frac{9657256}{9657700} = 99.99540\% & \frac{9585504}{9657700} = 99.25245\% & \frac{8248387}{9657700} = 85.40736\%\\

15 & \frac{7726132}{7726160} = 99.99964\% & \frac{7707122}{7726160} = 99.75359\% & \frac{7111664}{7726160} = 92.04655\%\\

16 & 1 & \frac{5308074}{5311735} = 99.93108\% & \frac{5106118}{5311735} = 96.12900\%\\

17 & 1 & \frac{3124058}{3124550} = 99.98425\% & \frac{3073350}{3124550} = 98.36136\%\\

18 & 1 & \frac{1562232}{1562275} = 99.99725\% & \frac{1553229}{1562275} = 99.42097\%\\

19 & 1 & \frac{657798}{657800} = 99.99970\% & \frac{656750}{657800} = 99.84038\%\\

20 & 1 & 1 & \frac{230160}{230230} = 99.96960\%\\

21 & 1 & 1 & \frac{65778}{65780} = 99.99696\%\\

22 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

23 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

24 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

25 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

26 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

\end{array}

$$

Probability Tables, Opposite-Colored Suits

Here we give the probability tables for selections from a two-opposite-suit deck (e.g., $\spadesuit, \heartsuit$) for solving the given sets of equations.

Opposite-Colored Suits, 1 Equation

$$

\begin{array}{c| c| c}

|T| & P(\text{1 short}) & P(\text{1 long}) \\\hline

0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 0 & 0\\

2 & 0 & 0\\

3 & \frac{228}{2600} = 8.76923\% & 0\\

4 & \frac{4750}{14950} = 31.77258\% & \frac{1384}{14950} = 9.25753\%\\

5 & \frac{40960}{65780} = 62.26817\% & \frac{26472}{65780} = 40.24324\%\\

6 & \frac{195859}{230230} = 85.07102\% & \frac{183868}{230230} = 79.86275\%\\

7 & \frac{627892}{657800} = 95.45333\% & \frac{640686}{657800} = 97.39830\%\\

8 & \frac{1543463}{1562275} = 98.79586\% & \frac{1560057}{1562275} = 99.85803\%\\

9 & \frac{3115188}{3124550} = 99.70037\% & \frac{3124390}{3124550} = 99.99488\%\\

10 & \frac{5307975}{5311735} = 99.92921\% & \frac{5311727}{5311735} = 99.99985\%\\

11 & \frac{7724994}{7726160} = 99.98491\% & 1\\

12 & \frac{9657446}{9657700} = 99.99737\% & 1\\

13 & \frac{10400566}{10400600} = 99.99967\% & 1\\

14 & \frac{9657698}{9657700} = 99.99998\% & 1\\

15 & 1 & 1\\

16 & 1 & 1\\

17 & 1 & 1\\

18 & 1 & 1\\

19 & 1 & 1\\

20 & 1 & 1\\

21 & 1 & 1\\

22 & 1 & 1\\

23 & 1 & 1\\

24 & 1 & 1\\

25 & 1 & 1\\

26 & 1 & 1\\

\end{array}

$$

Opposite-Colored Suits, 2 Equations

$$

\begin{array}{c| c| c| c}

|T| & P(\text{2 short}) & P(\text{1 short, 1 long}) & P(\text{2 long}) \\\hline

0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

1 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

2 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

3 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

4 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

5 & 0 & 0 & 0\\

6 & \frac{15706}{230230} = 6.82187\% & 0 & 0\\

7 & \frac{236622}{657800} = 35.97172\% & \frac{131366}{657800} = 19.97051\% & 0\\

8 & \frac{1133326}{1562275} = 72.54331\% & \frac{1255503}{1562275} = 80.36376\% & \frac{316134}{1562275} = 20.23549\%\\

9 & \frac{2854990}{3124550} = 91.37284\% & \frac{3095130}{3124550} = 99.05842\% & \frac{2649562}{3124550} = 84.79819\%\\

10 & \frac{5181320}{5311735} = 97.54478\% & \frac{5307710}{5311735} = 99.92422\% & \frac{5295834}{5311735} = 99.70064\%\\

11 & \frac{7675138}{7726160} = 99.33962\% & \frac{7724994}{7726160} = 99.98491\% & \frac{7725852}{7726160} = 99.99601\%\\

12 & \frac{9642050}{9657700} = 99.83795\% & \frac{9657446}{9657700} = 99.99737\% & \frac{9657692}{9657700} = 99.99992\%\\

13 & \frac{10397178}{10400600} = 99.96710\% & \frac{10400566}{10400600} = 99.99967\% & 1\\

14 & \frac{9657236}{9657700} = 99.99520\% & \frac{9657698}{9657700} = 99.99998\% & 1\\

15 & \frac{7726132}{7726160} = 99.99964\% & 1 & 1\\

16 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

17 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

18 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

19 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

20 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

21 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

22 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

23 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

24 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

25 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

26 & 1 & 1 & 1\\

\end{array}

$$

Large-selection Guarantees (Proposition 3)

By observing the above tables, one conclusion leaps out.

Corollary 8 In order to solve one long and one short equation, it suffices to gather 20 cards in like-colored suits, or 15 cards in opposite-colored suits.

We also should recall Observation 5 from the previous part.

Observation 5 (again)

- 8 cards from a single suit are guaranteed to solve a single short equation.

- 11 cards from a single suit are guaranteed to solve both a short equation and a long equation.

- 13 cards from a single suit can solve both long equations and a short equation.

We are now in a position to prove Proposition 3.

Proposition 3 (again) Any selection from a standard deck with 37 or more cards is enough to solve all 4 equations.

Proof, given Observation 5 and Corollary 8 We work by cases on the number of cards in each suit.

Case 1: At least 11 cards in at least 1 suit. If there are 11+ cards in at least 1 suit, say spades, then the spades can solve one short and one long equation. Also, as the number of cards in any one suit is at most 13, the number of cards in the other three suits is at least $37 - 13 = 24$.

Suppose, by way of contradiction, then there is no solution to the other short and long equation. Then:

$h + d \leq 19$ (since by Corollary 4, 20 cards from like-colored suits would solve one short and one long equation),

$c + d \leq 14$ (since by Corollary 4, 15 cards from opposite-colored suits would solve one short and one long equation),

$c + h \leq 14$ (ditto).

and adding these, $2(c + h + d) \leq 47$, so $c + h + d \leq 23 + \frac{1}{2}$. Yet our prior observation is that $c + h + d \geq 24$. Contradiction. Hence, this case also has a guaranteed solution.

Case 2: At most 10 cards in all suits. If every suit has at most 10 cards, then there must be 7 cards in each suit in the selection (essentially, because $10 + 10 + 10 + 6 = 36 < 37$). Moreover, there cannot be two suits with exactly 7 cards in the selection (because $10 + 10 + 7 + 7 = 34 < 37$). Hence, we must have that both $s + h$ and $c + d$ are bounded below by $7 + 8 = 15$; hence, the spades-hearts pair of suits solves one short and one long equation, and same for the clubs-diamonds pair of suits. Hence, we have a solution to the system of equations.

The list of cases being exhaustive, we are done. $\square$

18-card probabilities argument (Proposition 4)

Proposition 4 (again) If one selects 18 cards from a deck of cards (uniformly at random across all such 18-card subsets), then the probability of solving the equations is at least $62.9\%$.

Proof. We consider the split $\left \lbrace \spadesuit, \heartsuit \right\rbrace$, $\left\lbrace \clubsuit, \diamondsuit \right\rbrace$. We have

$$

\begin{aligned}

P(18\text{-card solution set}) = \sum_{j = 0}^{18} & \bigg( P(|\spadesuit| + |\heartsuit| = j, |\clubsuit| + |\diamondsuit| = 18-j)\\

& \cdot P \big( \text{solution set } \big| |\spadesuit| + |\heartsuit| = j |\clubsuit| + |\diamondsuit| = 18-j \big) \bigg)

\end{aligned}

$$

Similarly to the discussion in Proposition 2, the first probability is counting the number of ways to choose $j$ out of the $26$ spades and hearts, and independently choosing $18 - j$ out of $26$ clubs and diamonds, out of the $\binom{52}{18}$ selections of 18 cards. Hence, we have

$$

P(|\spadesuit| + |\heartsuit| = j, |\clubsuit| + |\diamondsuit| = 18-j) = \frac{\displaystyle \binom{26}{j} \cdot \binom{26}{18-j}}{\displaystyle \binom{52}{18}}.

$$

To efficiently write our underestimates for the conditional probabilities, let us write:

- $p_{SS}^{\text{Opp}}(t)$ to be the probability that a selection of $t$ cards from two opposite-color suits solves two short equations;

- $p_{SL}^{\text{Opp}}(t)$ to be the probability that a selection of $t$ cards from two opposite-color suits solves one short and one long equation;

- $p_{LL}^{\text{Opp}}(t)$ to be the probability that a selection of $t$ cards from two opposite-color suits solves two long equations.

Then we have three simple ways to solve the collection of 4 equations with a selection with $|\spadesuit| + |\heartsuit| = j$ and $|\clubsuit| + |\diamondsuit| = 18-j$:

Use spades and hearts to solve both short equations, and (independently) use clubs and diamonds to solve both long equations, with probability $p_{SS}^{\text{Opp}}(j) p_{LL}^{\text{Opp}}(18-j)$.

Use spades and hearts to solve one long and one short equation, and independently use clubs and diamonds to solve the other short and other long equation, with probability $p_{SL}^{\text{Opp}}(j) \cdot p_{SL}^{\text{Opp}}(18-j)$.

Use spades and hearts to solve both long equations, and clubs and diamonds to solve both short equations, with probability

$p_{LL}^{\text{Opp}}(j) p_{SS}^{\text{Opp}}(18-j)$.

These three events of solution types are not disjoint (see Remark 9), but for each choice of $j$, however, we may as well lower-bound by the option that gives us the best opportunities. Putting it all together, our lower bound is

\begin{align*}

P(18\text{-card solution set}) &= \sum_{j = 0}^{18} && \bigg( P(|\spadesuit| + |\heartsuit| = j, |\clubsuit| + |\diamondsuit| = 18-j)\\

& && \cdot P\big(\text{solution set } \big| |\spadesuit| + |\heartsuit| = j, |\clubsuit| + |\diamondsuit| = 18-j \big) \bigg)\\

& \geq \sum_{j = 0}^{18} && \Bigg( \frac{\displaystyle \binom{26}{j} \cdot \binom{26}{18-j}}{\displaystyle \binom{52}{18}}\\

& && \cdot \max \lbrace p_{SS}^{\text{Opp}}(j) p_{LL}^{\text{Opp}}(18-j), p_{SL}^{\text{Opp}}(j) \cdot p_{SL}^{\text{Opp}}(18-j), p_{LL}^{\text{Opp}}(j) p_{SS}^{\text{Opp}}(18-j) \rbrace \Bigg).

\end{align*}

With computational assistance, this sum turns out to be $\dfrac{13,433,550,949,076}{21,335,988,680,825} \approx 62.962\%$. $\square$.

Remark 9 Of course, splitting by pairing spades with diamonds and clubs with hearts yields the same result. By contrast, pairing spades with clubs and hearts with diamonds (pairing the like-colored suits) yields a weaker lower bound of $\dfrac{24,021,902,309}{86,380,520,975} \approx 27.809\%$.

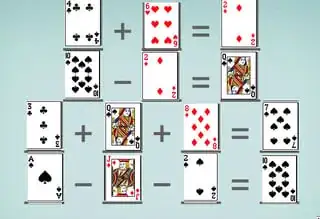

Remark 10 We now justify our claim of non-disjointness. We present a $16$-card selection can solve the equation in all three ways. Take the A-3 and 6 of spades and clubs, and A-4 of hearts and diamonds. Then we can solve the system of equations via all three assignments of two equations to the pairs $\left \lbrace \spadesuit, \heartsuit \right\rbrace$ and $\left \lbrace \clubsuit, \diamondsuit \right\rbrace$ as follows:

$$

\begin{array}{c | c}

\left \lbrace \spadesuit, \heartsuit \right\rbrace \text{ 1 Long, 1 Short} & \left \lbrace \clubsuit, \diamondsuit \right\rbrace \text{1 Long, 1 Short}\\ \hline

A_{\spadesuit} + 3_{\spadesuit} + (-2)_{\heartsuit} = 2_{\spadesuit} & A_{\clubsuit} + 3_{\clubsuit} + (-2)_{\diamondsuit} = 2_{\clubsuit}\\

(-A)_{\heartsuit} + (-3)_{\heartsuit} = (-4)_{\heartsuit} & (-A)_{\diamondsuit} + (-3)_{\diamondsuit} = (-4)_{\diamondsuit}

\end{array}

$$

$$

\begin{array}{c | c}

\left \lbrace \spadesuit, \heartsuit \right\rbrace \text{2 Long} & \left \lbrace \clubsuit, \diamondsuit \right\rbrace \text{2 Short}\\ \hline

A_{\spadesuit} + 3_{\spadesuit} + (-2)_{\heartsuit} = 2_{\spadesuit} & A_{\clubsuit} + 2_{\clubsuit} = 3_{\clubsuit}\\

6_{\spadesuit} + (-3)_{\heartsuit} + (-4)_{\heartsuit} = (-A)_{\heartsuit} & (-A)_{\diamondsuit} + (-3)_{\diamondsuit} = (-4)_{\diamondsuit}

\end{array}

$$

$$

\begin{array}{c | c}

\left \lbrace \spadesuit, \heartsuit \right\rbrace \text{2 Short} & \left \lbrace \clubsuit, \diamondsuit \right\rbrace \text{2 Long}\\ \hline

A_{\spadesuit} + 2_{\spadesuit} = 3_{\spadesuit} & A_{\clubsuit} + 3_{\clubsuit} + (-2)_{\heartsuit} = 2_{\clubsuit}\\

(-A)_{\heartsuit} + (-3)_{\heartsuit} = (-4)_{\heartsuit} & 6_{\clubsuit} + (-3)_{\diamondsuit} + (-4)_{\diamondsuit} = (-A)_{\diamondsuit}

\end{array}

$$

Miscellaneous Remarks (can skip this)

Measuring the Combinatorial Explosion (or, why we have not proceeded further)

We split the discussion by each frontier.

"Why not extend the two-suit case to three equations?"

Let us just consider the difficulty of finding the basic solutions. For the one-suit case, it took between 50 minutes and 1 hour to find the basic solutions, for each of the cases, 2-short-1-long and 1-short-2-long. Moreover, these equation sets have $|V| = 10$ or $|V| = 11$. As $\frac{\displaystyle \binom{26}{10}}{\displaystyle \binom{13}{10}} = 18572 + \frac{1}{2}$ and $\frac{\displaystyle \binom{26}{11}}{\displaystyle \binom{13}{11}} = 99053 + \frac{1}{3}$, it would likely take tens of thousands of hours of computing time on my current machine to get these results. This is not feasible for me.

Can we say anything about three-suit or four-suit cases, for one equation?

For a single equation, even with the full deck, I can find the basic solutions in a reasonable amount of time. The super-set-finding phase is much harder here, just because of the number of subsets to check. For example, for a three-suit deck and a single long equation, around $|T| = 9$, I had to switch from a parallel approach to a serial approach, because I used a simple parallelization protocol (to simplify error-testing) and the overhead was using up too much RAM. In the serial approach (still 3 suits and 1 long equation), checking $|T| = 10$ took more than half a day by itself. This is just for the relatively small $\displaystyle \binom{39}{9} = 211,915,132$ and $\displaystyle \binom{39}{10} = 635,745,396$.

Handling the complete problem by brute-force would tax a supercomputer.###

Note that $\displaystyle \binom{52}{18} = 42,671,977,361,650$, or over 42 quadrillion. To solve the problem in a (non-leap) year on a single processor, each subset would have to be checked in (just) under 0.74 microseconds. To put it another way, to finish in a non-leap year, and assuming each case was solved in a tenth of a second, we would need 13,531 processors to run for the whole year, plus about a fifth of the year from a 13,532nd processor. This seems unrealistic to me.

An Extension that Might Work

Note that we could not really combine our one-suit statistics with our two-suit statistics, as the cases are not disjoint. For example, "solving a single short equation in spades and clubs" and "solving a single short equation in spades alone" has obvious overlap.

What might work is to break down our two-suit results by per-suit counts: for example, replacing "all 10-card selections from hearts and diamonds" with "all selections of 8 hearts and 2 diamonds". That might allow us to eke out a little more evidence. Each individual case would presumably be faster, but the total would probably take longer, and I would need to greatly re-work the code. I am getting burnt out, so I will not proceed with this unless there is great interest.

An Emergent Phenomenon That Might be its own Question

Comparing the like-colored suits and opposite-colored suits statistics, we see one easy-to-state phenomenon.

For all subset sizes, like-colored suits have the advantage when solving one or two short equations,

and opposite-colored suits have the advantage when solving one or two long equations.

One might be tempted to suppose that it is merely whichever case has the more numerous basic solutions, but this is easy to

repudiate. We need only consider the statistics for a deck of two opposite-color suits and the single-equation statistics:

$$

P(1 \text{ short equation solved with } 4 \text{ cards}) = \frac{4750}{14950} > \frac{1384}{14950} = P (1 \text{ long equation solved with } 4 \text{ cards})

$$

but

$$

P(1 \text{ short equation solved with } 7 \text{ cards}) = \frac{627892}{657800} < \frac{640686}{657800} = P(1 \text{ long equation solved with } 7 \text{ cards})

$$

It is a matter of the spread of the subsets, as well as their count, that influence the number of solving supersets.

It would be nice if we could get a human-readable explanation for why this would happen. If there is interest, it should probably be its own Math.SE question.