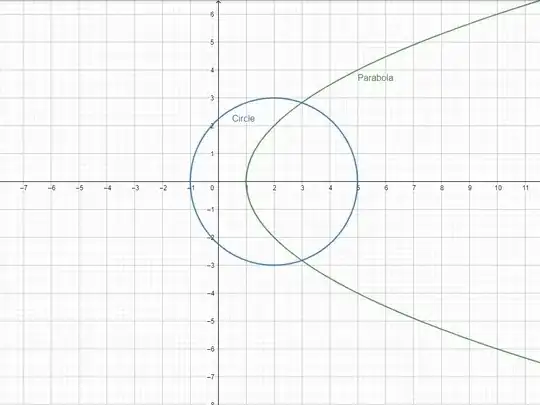

We have a parabola and a circle with the following equations and their graph placed at the end of my question.

Parabola: $y^2 = 4x -4$

Circle: $(x-2)^2 + y^2 = 9$

My goal was to calculate their intersection points so I substituted $y^2$ from the parabola equation into the circle equation and I got

$(x-2)^2 + (4x-4)=9 \implies x^2 - 4x + 4 + (4x - 4) = 9 \implies x^2 = 9 \implies x = \pm3$

$x=3$ is the only correct solution but why is $x=-3$ produced as an extra invalid solution?

What is the exact mathematical explanation behind this? Why substituting one equation into the other has produced extra answers?

update

When I calculate $x$ from the parabola equation and substitute it in the circle equation, I don't get any extra answers for $y$:

$y^2=4x-4 \implies y^2 +4 = 4x \implies x = \frac{y^2}{4} + 1$

$(x-2)^2 +(4x-4)=9 \implies ((\frac{y^2}{4} + 1) - 2)^2 + (4x - 4)=9 \implies y^4 +8y - 128 = 0 \implies y^2=8,-16$

$y^2 = -16$ cannot be true so $y^2 = 8 \implies y=\pm 2\sqrt{2}$ and these are correct answers for $y$.

2nd update

I made a mistake in the calculation in the previous update although the final solutions where correct. I write the correct calculation:

$(x-2)^2 +y^2=9 \implies ((\frac{y^2}{4} + 1) - 2)^2 + y^2=9 \implies (\frac{y^2}{4} - 1)^2 + y^2=9 \implies (\frac{y^4}{16} - \frac{y^2}{2} + 1) + y^2=9 \implies \frac{y^4}{16} + \frac{y^2}{2} + 1=9 \implies (\frac{y^2}{4} + 1)^2=9 \implies (\frac{y^2}{4} + 1)=\pm3 \implies \frac{y^2}{4} =2,-4 \implies y^2=8,-16$