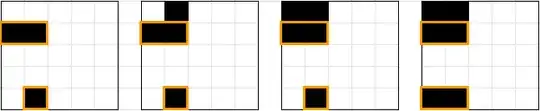

Consider separately two ways the infection can grow. When infection spreads to an empty cell, it can be that two of the adjacent infected cells share a corner (which is always the case when there are three or four adjacent infected cells) or not, in which case the two infected cells are both in the same row or column.

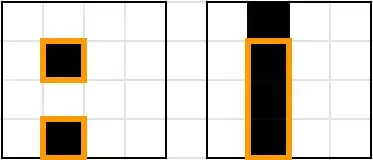

Within a row or column, we will say a component is a group of consecutive infected cells in that row or column. (We don't care whether the infected cells are connected via a path that lies outside the row or column.) Our proposed invariant is based on the total number of components among both rows and columns (with an exception noted below).

We will consider growth not in generations, but in individual steps where the infection grows to only a single cell at each step. (The order will not matter unless noted.)

Under the first kind of growth, new components cannot be created. The step can only decrease the number of components in a row or column or both.

Under the second kind of growth, usually the number of components of a single row or column will go down by one (as the components are joined by the infection of the cell between them) and the number of components in the corresponding column or row will either increase by one or stay the same. In this case, then, the total number of components will not increase.

The other case is when the last cell in the row or column is being infected. The first time this happens for rows and the first time for columns, it can indeed increase the number of components by one. However, we not need to concern ourselves with subsequent times. Without loss of generality, consider rows. If one row is already completely infected and a second row is one cell from being completely infected, then either there is a column component that connects these row components or not. If there is a connecting column component, then (by infecting in a different order) the first kind of growth can be used to infect the entire stripe bounded by the rows and the connecting component. (This includes the last cell in this new row which will have been infected without increasing the number of components.) If there is no such connection, then in $n - 1$ columns, there are at least $2$ components each plus at least $1$ component in the last column plus $2$ rows with at least one component. This is at least $2n + 1$ total components. We will not be concerned with cases that have so many components.

If we start with $n - 2$ infected cells, then there are at most $n - 2$ column components and $n - 2$ row components for a total of $2n - 4$ components. At most two new components can be introduced; one by the first full row infection and one by the first full column infection. This gives at most $2n - 2$ components. As this is less than $2n + 1$, any subsequent full row or column infection can be completed by growth of the first kind without increasing the number of components. Thus, the final number of components will be at most $2n - 2$. This is less than the $2n$ of the completely infected board.