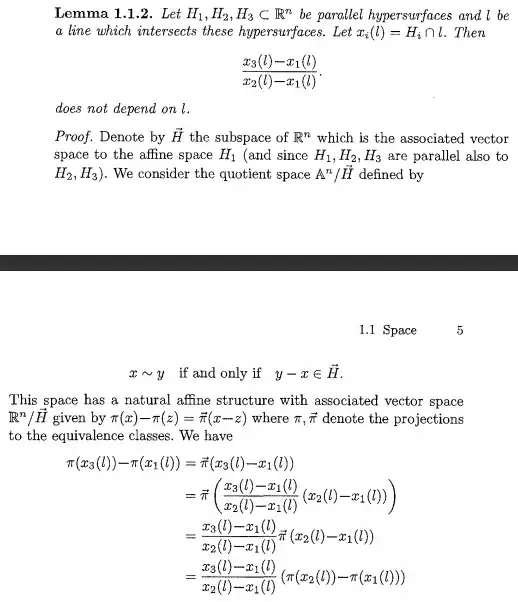

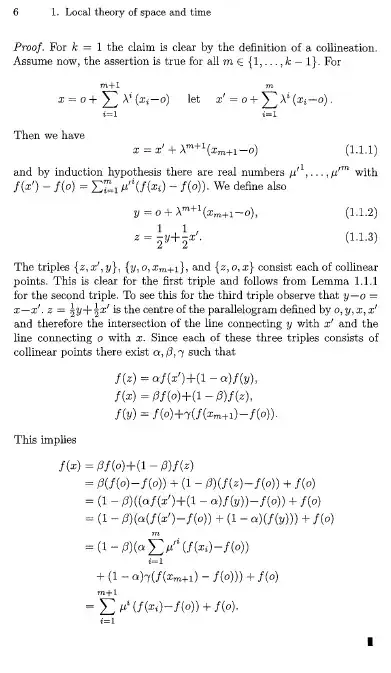

First let me sketch an alternative proof of the lemma, which may provide some insight:

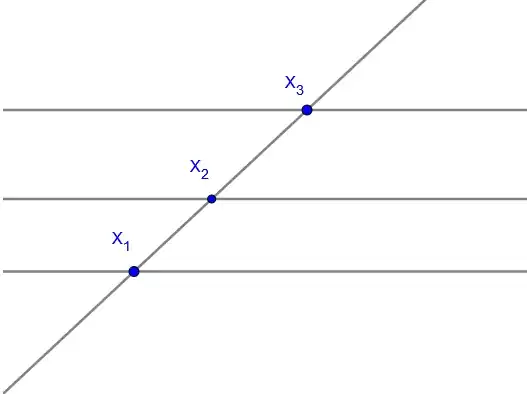

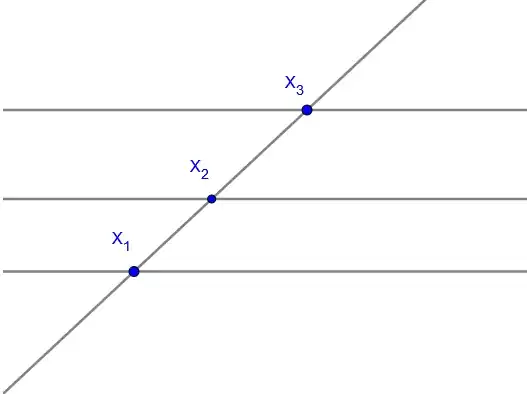

Given any pair of lines $l_1$ and $l_2$, there is a line $l_0$ that meets both lines and is not parallel to the planes $H_i$. For example, you could take $l_0:=x_1(l_1)x_2(l_2)$, assuming that $H_1\neq H_2$ as otherwise the lemma fails. Then $l_0$ and $l_1$ are coplanar, and $l_0$ and $l_2$ are coplanar, and so it suffices to show that the ratio does not depend on $l$ in these planes. That is, it suffices to prove the claim in dimension 2, for which we can draw a picture:

This simple case is of course an elementary exercise.

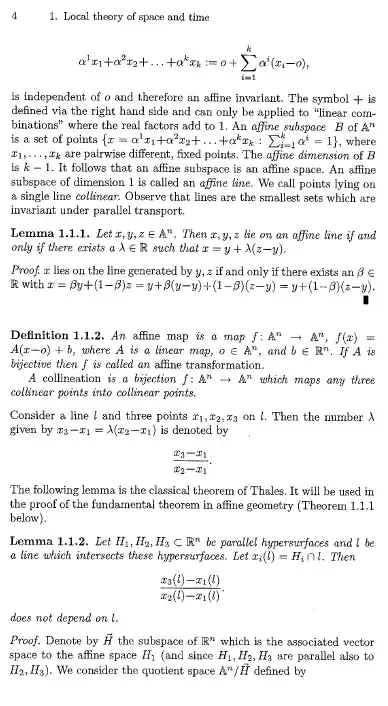

As for the proof in the book: First observe that the definition of $\frac{x_3-x_1}{x_2-x_1}$ makes no sense if $x_1=x_2$, and hence that the statement of the lemma makes no sense if $H_1=H_2$. The notation $\frac{x_3-x_1}{x_2-x_1}$ is also very misleading as it suggests some algebraic properties of (differences of) vectors, which they don't have. This is illustrated by some confusion in the proof itself, which contains the expression

$$\frac{\pi(x_3(l))-\pi(x_1(l))}{\pi(x_2(l))-\pi(x_1(l))}.$$

This fails to make sense for some line $l$ even if $x_1(l)\neq x_2(l)$ and $H_1\neq H_2$.

As for your questions about the notation:

As you can see, the author uses projection maps $\pi$ and $\vec\pi$ but no definitions of these maps have been given.

This is not true; the author defines these maps in the same sentence where he first mentions them (emphasis mine):

This space has a natural affine structure with associated vector space $\Bbb{R}^n/\vec H$ given by $\pi(x)-\pi(z)=\vec\pi(x-z)$, where $\pi$, $\vec\pi$ denote the projections to the equivalence classes.

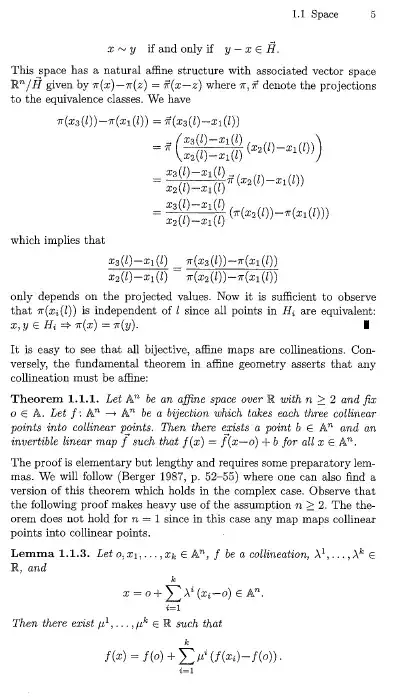

It is slightly ambiguous which projection map is which, but given that the expression

$$\pi(x)-\pi(z)=\vec\pi(x-z),$$

is supposed to be a definition of an affine structure on $\Bbb{A}^n/\vec H$, the sensible interpretation is that $\pi$ is the quotient map on $\Bbb{A}^n$ and $\vec\pi$ is the quotient map on $\Bbb{R}^n$. Explicitly, if $[x]\in\Bbb{A}^n/\vec H$ denotes the equivalence class of $x\in\Bbb{A}^n$, the quotient maps are given by

\begin{eqnarray*}

&&\pi:\ \Bbb{A}^n \longrightarrow \Bbb{A}^n/\vec H:\ x\ \longmapsto\ [x],\\

&&\vec\pi:\ \Bbb{R}^n \longrightarrow \Bbb{R}^n/\vec H:\ x\ \longmapsto\ x+\vec H.\\

\end{eqnarray*}

The latter is the quotient map of $\Bbb{R}^n/H$, and it should be familiar to you if you have taken linear algebra. See the Wikipedia page for basic properties of this map. The only property used is that it an $\Bbb{R}$-linear map.

As the question is tagged book-recommendation, if any of the above is still unclear (either my answer or the fragment you posted), I would recommend to pick up a book on linear algebra that takes an abstract approach. I can't recommend any particular book, but in my humble opinion you should be able to flip through Linear Algebra done wrong comfortably before attempting to read your book.