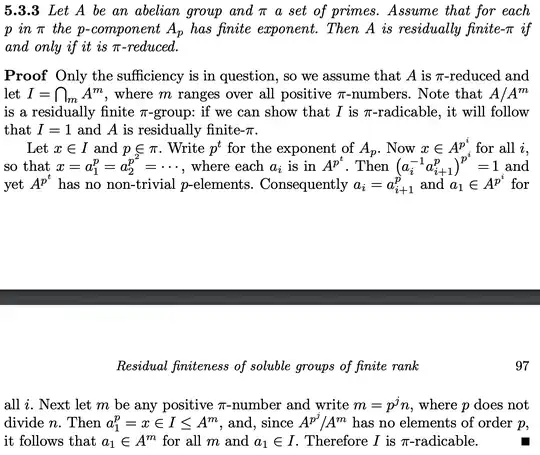

Suppose $A$ is an abelian group and $\pi$ is a set of prime numbers. A $\pi$-number is a product of primes from $\pi$.

Assume that for each $p \in \pi$, $A_p = \{a \in A : \exists i\in\mathbb{N} \text{ s.t } a^{p^i} = 0\}$ has finite exponent.

Assume also that $A$ is $\pi$-reduced; there are no non-trivial subgroups of $A$ which are $\pi$-divisible. That is, for any $H \leq A$ there is $h \in H$ and $m$ a $\pi$-number such that for any $x \in H$, $x^m \neq h$.

Let $j \in \mathbb{N}$, $p \in \pi$ and $m = p^jn$ a $\pi$-number where $n$ is relatively prime to $p$.

why is $A/A^m$ residually finite?

why does $A^{p^j}/A^m$ have no element of order $p$?

Here is the context from Infinite Soluble Groups: