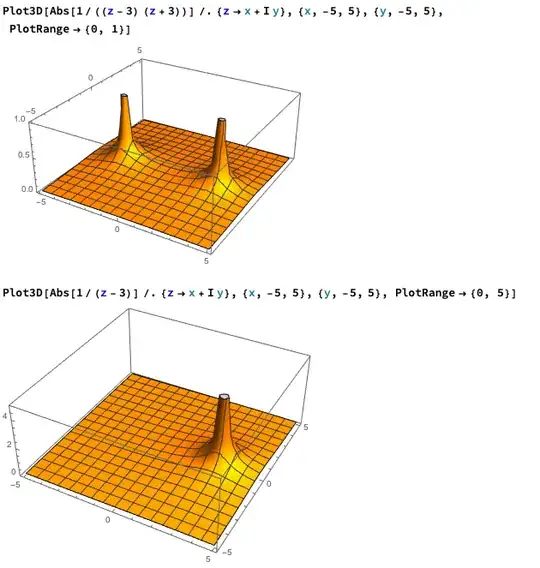

I don't know exactly what qualifies as an answer here, but the picture in my head that goes along with partial fractions is just the usual picture of rational singularities in the complex plane.

For instance, $\frac{1}{z^2-9}$ has singularities at $z=\pm 3$, while $\frac{1}{z -3}$ only has a singularity at $z=3$. When plotting the modulus of this function in the complex plane, this is obvious:

Clearly to get the pictures to look the same at all you'll need to add something like $\frac{1}{z+3}$ to $\frac{1}{z-3}$--that'll at least make sure they blow up at the right points. Moreover you can't use other denominators since then they'd blow up at the wrong places.

Near a singularity, the function is totally dominated by that singularity, so the orders of the singularities have to match up. For instance, if you start with $\frac{1}{(z-3)^2(z+3)}$, you'll definitely need to use a summand like $\frac{1}{(z-3)^2}$ and not just $\frac{1}{z-3}$, and also $\frac{1}{(z-3)^3}$ blows up "too much" so you'd need to avoid that.

Of course, if you add up $\frac{1}{(z-3)^2}$ and $\frac{1}{z-3}$ you'll get something subtly different from either, so you'll need to "keep around" the lower order terms.

Altogether, this seems like a pretty good "visual" justification for

$$\frac{p(z)}{\prod_{i=1}^n (z-\zeta_i)^{a_i}} = \sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^{a_i} \frac{\alpha_{ij}}{(z-\zeta_i)^j}.$$

The fact that it works purely algebraically outside of the algebraically closed case or when you haven't split the denominator into linear factors is not hard to prove, of course, and you can get intuition for those versions from this one.

(For the record, at a glance I did not find the integration by parts picture intuitive. I find the product rule intuitive and that is my justification for integration by parts.)

.

.