The most common answer to this question "What is tangent to any curve?" is as follows:

"Tangent to a plane curve at a given point is the straight line that "just touches" the curve at that point. "

But this definition have two problems.

First is what do you mean by "just touches"? How can I know if a line "just touches" a curve or not?

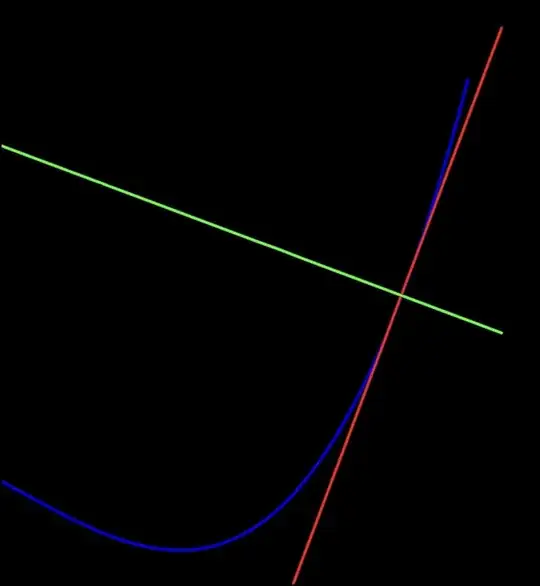

For example: How do you know that the red line in the following image "just touches" the curve while green line doesn't?

Second problem is that this definition doesn't generalize to the "straight-line curve" .

A tangent to a straight line is the straight line itself. But this can't be possible under the "just touches" definition. (This is just what I think, if you think my reasoning is incorrect then please correct me.)

So what is tangent to any curve? And also if my objections are correct then why is this definition so famous?