Zermelo–Fraenkel Set Theory is a system of axioms for describing set theory.

For example, Zermelo–Fraenkel Set Theory says things like:

For any set $x$ and any set $y$ there exists a set $z$ such that $x \in z$ and $y ∈ z$.

I have a conjecture, and my question is, "Is my conjecture provable using only Zermelo–Fraenkel Set Theory and basic logic?"

The conjecture itself is extremely simple. However, the formal wording is ugly, so I have moved the formal conjecture to the very end of this post. If you like formalism, and hate sloppiness, then feel free to scroll of the bottom.

First, let us look at at an informal description:

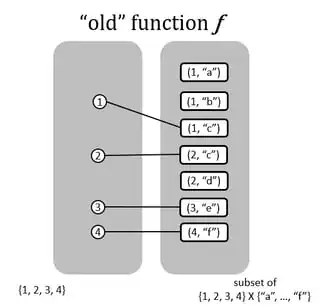

We start off by being handed a function named $f$:

- The inputs of $f$ are natural numbers.

- The outputs of $f$ look like $(4, x)$ or $(9, y)$

- Every output of function $f$ is an ordered pair

- The left-most element of the pair is a natural number.

- We do not know exactly what the right-hand element is.

The function $f$ has one more special property:

- INFORMAL EXAMPLES:

- $f(45)$ cannot be something like $(98, x)$

- $f(45)$ must be $(45, x)$ for some $x$

- The numbers must match.

- FORMAL GENERALITY:

for some set $B$, $\forall k \in \mathbb N$, $\forall p \in \mathbb N$, $\forall b \in B$, if $f(k) = (p, b)$, then $k = p$.

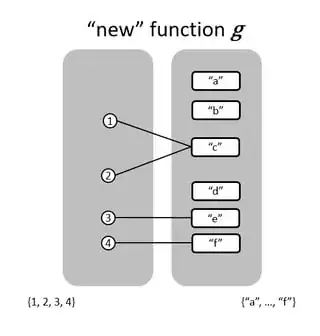

We want to show that, if function $f$ exists, then the relation $g$ constructed from $f$ by removing the left-hand numbers in the ordered pairs is a function.

For example, if $f(89) = (89, x)$ then $g(89) = x$.

Formally, if there exists a set $B$ such that

$f$ is a mapping from $\mathbb{N}$ to $(\mathbb{N} \times B)$, then $g = \{(k, b): \text{$k \in \mathbb{N}$ and $b \in B$ and $f(k) = (k, b)$}\}$.

BEGIN FORMALIZATION OF THE CONJECTURE:

For any set $B$, if there exists a function $f$ from $\mathbb{N}$ to $(\mathbb{N} \times B)$ such that for every $k$ in $\mathbb N$, there exists $b$ in $B$ such that $(k, (k, b))$ is in $f$, then there exists a function $g$ from $\mathbb N$ to $B$ such that for all $k \in \mathbb N$, $f(k) = (k, g(k))$.