Let us consider the polynomial $p$ over a complex filed defiend by $$p(z_1,z_2,z_3):= z_{1}^2 +z_{2}^{2} +z_{3}^2 −2z_{1}z_{2} −2z_{1}z_{3} −2z_{2}z_{3}~~~ \forall z_{1}, z_{2}, z_{3}\in \mathbb{C}.$$ It is well known in the book ``Completely bounded maps and operator algebras" (Page-64) by Vern Paulsen that \begin{align} \sup\{\vert p(z_{1}, z_{2}, z_{3})\vert: \vert z_{1}\vert, \vert z_{2}\vert, \vert z_{3}\vert\leq 1, z_{1}, z_{2},z_{3}\in \mathbb{C} \}=5. \end{align} As I know the only basic complex analysis up to one variable, I am facing difficulties to calculate it. Thus, I will appreciate if someone give me clarity of the last equality.

-

Wouldn't Lagrange multipliers help in this case? – b00n heT Jun 11 '20 at 06:47

-

I tried a few things that didn't work out, but I feel like we can factorize the polynomial in some clever way and apply Cauchy Schwarz – Ben10 Jun 11 '20 at 07:51

-

First, prove that $\sup_{|z_1|\le 1, |z_2|\le 1, |z_3|\le 1} |p(z_1, z_2, z_3)| = \sup_{|z_1| = 1, |z_2| = 1, |z_3| = 1} |p(z_1, z_2, z_3)|$. – River Li Jun 12 '20 at 13:43

2 Answers

The supremum is as least $5$ because $p(1, 1, -1) = 5$. It remains to show that $$ \tag{*} |p(z_1, z_2, z_3)| \le 5 $$ for all complex numbers $z_1, z_2, z_3$ in the closed unit disk.

As a polynomial, $p$ is holomorphic in each variable. Therefore (maximum modulus principle!) it suffices to prove $(*)$ for $|z_1| = |z_2| = |z_3| = 1$.

Let $u$ be a complex number with $u^2 = z_1/z_2$ and set $z = - z_3/(u z_2)$. Then $|u|=|z|=1$ and $$ |p(z_1, z_2, z_3)| = \left| (z_1+z_2-z_3)^2 - 4z_1z_2 \right| \\ = \left| \frac{(z_1+z_2-z_3)^2}{z_1z_2} - 4\right| = \left| \left( u + \frac 1u + z\right)^2 - 4\right| = \left| \bigl( 2 \operatorname{Re}(u) + z\bigr)^2 - 4\right| \, . $$

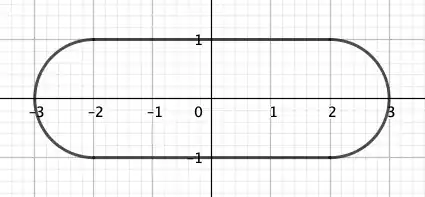

Therefore it suffices to prove that $$ |(a+z)^2 -4 | \le 5 $$ for all real $a$ with $-2 \le a \le 2$ and all complex $z$ with $|z| \le 1$, or equivalently, $$ \tag{**} |w^2-4| \le 5 $$ for all complex $w$ inside or on the boundary of the following domain:

Using the maximum modulus principle again, it suffices to prove $(**)$ for all $w$ on the boundary of that domain.

On the right semicircle we have $|w-2| = 1$ and then $$ |w^2-4| = |(w-2)(w+2)| = |w+2| \le |w| + 2 \le 3 + 2 = 5 \, . $$ The same argument works on the left semicircle. It remains to consider the case where $w = x \pm i$ with $-2 \le x \le 2$. In that case $$ w^2-4 = (x \pm i)^2-4 = x^2 - 5 \pm 2xi \\ \implies |w^2-4|^2 = (x^2-5)^2 +4x^2 = x^2(x^2-6) + 25 \le 25 \\ \implies |w^2-4| \le 5 \, . $$ This finishes the proof.

We can also see when equality holds: In $(**)$ equality holds if and only if $w = \pm 3$ or $w = \pm i$.

- If $w = \pm3$ then $u=z = \pm 1$ and therefore $z_1 = z_2 = -z_3$.

- If $w = \pm i$ then $u = \pm i$ and $z = \pm i$ and then $z_1 = -z_2 = z_3$ or $-z_1 = z_2 = z_3$.

- 128,226

-

"and all complex $z$ with $|z|≤1$" Should not it be "with $|z|=1$" here? (I do not doubt that both conditions are equivalent in the considered case). – user Jun 14 '20 at 14:00

-

@user: They are in fact equivalent. I chose this version (and wrote “it suffices to prove that ...”) because I found that it makes it a tiny bit easier to see the connection to (**). – Martin R Jun 14 '20 at 14:07

Let $z=[z_1\quad z_2\quad z_3]^T$ and $B\in\mathbb{R}^{3\times3}$, then lets look at the following problem

\begin{array}{ll} \text{sup} & z^TBz\\ z_i\in\mathbb{R}\\ \text{s.t.} & |z_i|\leq1\end{array}

Let $A=B-I$ then $z^TBz=z^TAz+z^Tz$.

\begin{array}{ll} \text{sup} & z^TBz= \text{sup} & (z^TAz+z^Tz) \leq \text{sup} &(z^TAz)\quad+\quad \text{sup}&(z^Tz)\\z_i\in\mathbb{R}\\ \text{s.t.} & |z_i|\leq1\end{array}

Notice that if we remove $z^Tz$ from above problem the optimization problem becomes convex if $A\geq0$ and optimal solution is achieved at $|z_i|=1$, and definitely $\text{sup}(z^Tz)=3$ is achieved at $|z_i|=1$.

For your case $B=\begin{bmatrix}1&-1&-1\\-1&1&-1\\ -1&-1&1\end{bmatrix}$ and $A=\begin{bmatrix}0&-1&-1\\-1&0&-1\\ -1&-1&0\end{bmatrix}\geq0$. Then you can check the results for $\text{sup}(z^TAz)$ at $|z_i|=1$ from here. Since $A$ represents unbalanced graph, $z^TAz<\sum |a_{ij}|$, the best you can achieve is $\text{sup}(z^TAz)=2$, for example at $z=[1 \quad1\quad -1]^T$.

EDIT: I notice that my answer holds only for $z_i\in\mathbb{R}$, not sure if it holds for complex numbers.

- 1,978

-

-

-

The issue with $3$ has become clear. Another question: how the estimate $\sup z^T A z=2$ was obtained. To justify this you refer to an answer about real domain which clearly has "corners". Here however $z_k=e^{i\phi}$, therefore I would assume that the reference you given is not sufficient. – user Jun 11 '20 at 09:01

-

@user yes, I notice later that original question was over complex $z_i$, and my answer holds for real $z_i$. I will keep the answer anyway, maybe it will be still useful – Lee Jun 11 '20 at 09:03