Claim:$\;$If $n\ge 4$, player $0$ has a winning strategy.

The idea is simple, and in essence just a variation of Aravind's beautiful solution for the even case.

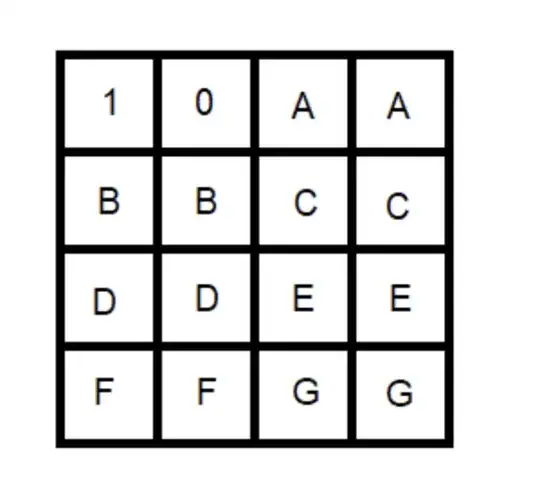

Of the first $4$ rows, call rows $1$ and $2$ a complementary pair, and similarly, call rows $3$ and $4$ a complementary pair.

In a complementary pair of rows, call two cells in the same column a complementary pair of cells.

Let $u$ be the $n$-vector with all entries equal to $1$.

As Aravind explained, if the completed matrix is such that each of the two complementary pairs of rows has sum equal to $u$ (i.e., $R_1+R_2=u=R_3+R_4$), then those $4$ rows are linearly dependent, hence the determinant is zero.

A two-phase winning strategy for player $0$ is as follows . . .

Phase $1$ strategy:

Whenever player $1$ places $1$ in a blank cell in one of the first $4$ rows for which the complementary cell is blank, player $0$ responds by placing $0$ in the complementary cell.

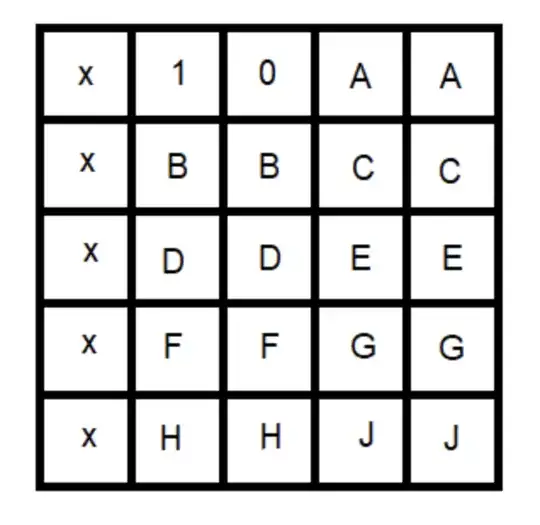

If player $1$ plays outside the first $4$ rows, player $0$ does the same, unless all cells outside the first $4$ rows are already filled, in which case, the strategy for player $0$ switches to the phase $2$ strategy.

Note that for even $n$, the number of cells outside the first $4$ rows is even, hence, assuming player $0$ has followed the phase $1$ strategy, there will never be a scenario where player $1$ fills the last blank cell outside the first $4$ rows. It follows that for even $n$, the game will run to completion with no need for player $0$ to switch to the phase $2$ strategy, and at completion, all pairs of complementary cells sum to $1$, so player $0$ wins.

So now assume:

- $n$ is odd.$\\[2pt]$

- It's player $0$'s turn.$\\[2pt]$

- Player $1$ has just filled the last remaining blank cell outside the first $4$ rows.

Player $0$'s strategy now switches to phase $2$ . . .

Phase $2$ strategy:

Given that player $0$ faithfully followed the phase $1$ strategy, it follows that for every pair of complementary cells, either both cells are filled (and sum to 1) or both cells are blank.

If there are no blank cells, then the game is over and player $0$ has won.

Otherwise, player $0$ chooses some pair of complementary blank cells and places $0$ in one of those cells.

From that point on, player $0$'s basic strategy is to place $0$ is some cell to ensure that whenever it's player $1$'s turn to play, there is exactly one pair of complementary cells for which one of the two cells contains $0$ and the other one is blank.

To accomplish the phase $2$ basic strategy, player $0$'s choice of move depends on the nature of player $1$'s previous move. There are two cases . .

If player $1$ places $1$ in a cell for which the complementary cell is blank, player $0$ responds by placing $0$ in that complementary cell.

If player $1$ instead places $1$ in a cell for which the complementary cell contains $0$, and if the game is not over, there must be at least one pair of complementary blank cells, so player $0$ responds by placing $0$ in one of the cells of such a complementary pair.

In either case, after player $0$'s response, there is exactly one pair of complementary cells for which one of the two cells contains $0$ and the other one is blank.

Assuming player $0$ faithfully follows the phase $2$ basic strategy, player $1$'s last move will be in a blank cell (the only remaining blank cell) for which the complementary cell contains $0$, and at that point, all pairs of complementary cells sum to $1$, hence player $0$ has won.

This completes the proof.