I find that many times a beginning student fails to fully appreciate what transitivity is when it is worded like it usually is. In particular, I find that students miss out on the fact that the transitive closure might include more than just what is immediately missing. As such, I recommend thinking of it in the following way.

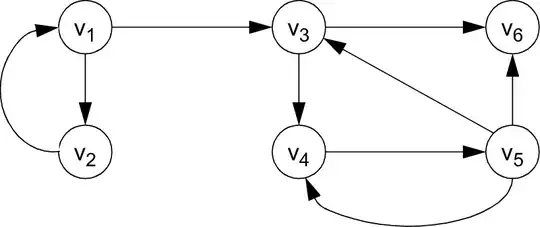

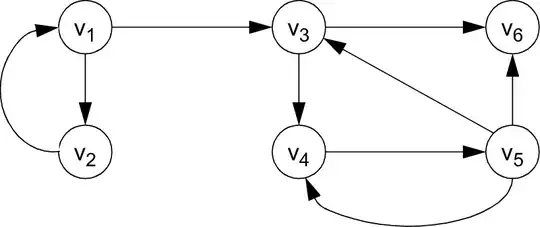

Imagine a directed multigraph like the following:

Specifically, for your relation, have a vertex like $v_1,v_2,\dots$ for each of the elements in your underlying set and draw an edge with an arrow from one vertex to another if the first element is related to the second element by your relation. If that second element is again related back to the first element, you can choose to draw this as another parallel edge with an arrow in the reverse direction, or if you prefer you might choose to instead draw this as a edge with an arrow pointing in both directions like $\leftrightarrow$. If an element is related to itself, draw an edge with an arrow that leaves the vertex and points right back to the same vertex, what we call a "loop."

The above example is the graphical representation of the relation $$R=\{(1,2),(1,3),(2,1),(3,4),(3,6),(4,5),(5,4),(5,6)\}$$

Now... with these arrows, it becomes easier to imagine "moving around" on the graph. A "directed walk" on this graph can be thought of as some sequence of movements from one vertex to another where we travel along edges in the direction of an arrow. For example, I can start at $v_1$ and travel to $v_2$ then back to $v_1$ again then over to $v_3$ and end at $v_6$ if I so choose, and this sequence of movements I can call a directed walk from $v_1$ to $v_6$.

Now... a relation (and it's graph) is considered "Transitive" iff for any directed walk that I can do there is a shortcut using only a single edge in total.

That is... with the way transitivity is normally worded we have for instance $(1,3)\in R$ and $(3,6)\in R$ so if the above relation were in fact transitive, then I would need for $(1,6)$ to be in $R$ as well. It is not, so the above relation happens to not be transitive.

Something which I feel is particularly lacking in the usual way transitivity is described that my above description does better at is in reinforcing the idea that the directed walk can be of any length, not just a directed walk of length two using two edges. In the above, we also have $(1,3),(3,4),(4,5)$ so since there is a directed walk from $1$ to $5$, for the relation to be transitive we would need $(1,5)$ too! Further, we can have a walk that starts and ends in the same place! In the usual way of writing it, we have it written as $a$'s, $b$'s and $c$'s... but we do not require that $a,b,c$ all be distinct vertices! They can repeat values.

Now... the transitive closure of a relation is the relation which includes all missing necessary "shortcuts" for all currently possible directed walks. That is to say, it is the smallest relation which is transitive and contains the original relation as a subset.

For your relation, it is a much smaller example. Try drawing it out. There are four vertices, $v_1,v_2,v_3,v_4$, and the corresponding graph will start with $5$ edges (one of which is a loop from $3$ to itself). What shortcuts are missing for directed walks that we can perform?

We can do a walk from $1$ to $3$ and from $3$ back to $1$ again, so we need a shortcut from $1$ to $1$ so we are missing $(1,1)$ in the transitive closure. What else?

$~$

We can't actually travel from $1$ to $2$. Remember, we can't travel backwards along an edge... you should see that once you are at $1$ you can only stay at $1$ or go to $3$ or travel back and forth between $1$ and $3$. So, we don't need a shortcut from $1$ to $2$ since there weren't any directed walks we could take from $1$ to $2$ to begin with.

As an additional aside, many of the usual properties we are interested in for relations can be described quite easily using the language of graph theory.

Reflexivity: All vertices have a loop. (Originally: for all $x\in X$ we have $(x,x)\in R$)

Symmetry: All arrows (not loops) if any exist are double-sided. That is, if you can go from $a$ to $b$ in a single step, then you can go from $b$ to $a$ in a single step. (Originally: if $(a,b)\in R$ then $(b,a)\in R$).

Antisymmetry: All arrows (not loops) if any exist are single-sided. That is, if you can go from $a$ to $b$ (with $b$ different than $a$) in a single step, then you can not go from $b$ to $a$ in a single step. (Originally: if $(a,b)\in R$ and $(b,a)\in R$ then $a=b$)