The area of a spherical triangle with angles $\alpha$, $\beta$ and $\gamma$ on the 2-dimensional unit sphere is $\alpha + \beta + \gamma - \pi$. There is a nice geometrical proof of this fact that only uses the fact that the area of the whole sphere is $4\pi$, and the intuitively obvious fact that two great circles that cut at an angle $\alpha$ (necessarily in two antipodal points), bound two slices whose common area is $4\alpha$.

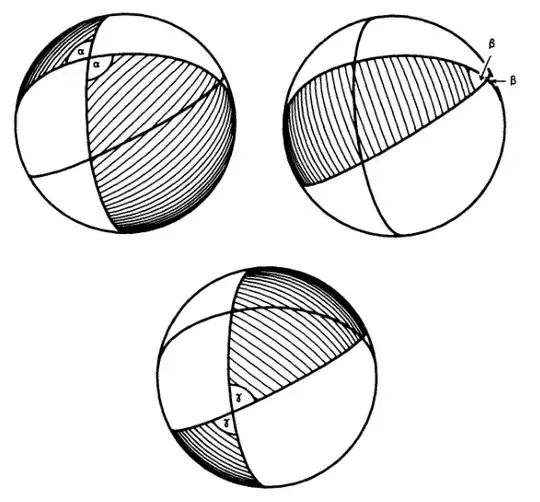

To prove it, you can construct three such (pairs of) regions, that together disjointly cover the sphere except for the triangle and its antipodal image, which are both triply covered, from which it follows. The following image, from Jeffrey Weeks' The Shape of Space, make it very clear:

The corresponding fact for hyperbolic triangles (on the hyperbolic plane with curvature -1) is

$$A = \pi - (\alpha + \beta + \gamma).$$

Would it be possible to prove this is a similar way? Obviously it cannot directly be related to the area of the whole space, but maybe it can be related to the area of some standard triangle, like the one all of whose angles are 0 and which can be realized in the upper half-plane model as the triangle bounded by a half circle centered on the real line and two vertical lines. You would just compute the area of this triangle once and for all.

The kind of answer I would like to see is a proof in which you obtain the area of a general triangle in terms of this reference area in some clever way by applying isometries and the fact that the area of a disjoint union is the sum of the areas, and little more (no integration).