I am pretty sure the following topic has already been introduced and studied somewhere, but I have not found references so far, so any help would be gladly welcome!

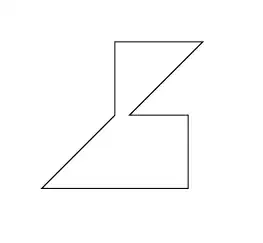

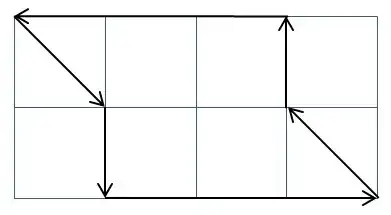

One can define a map $f$ on polygons as follows: assume the boundary of a polygon is seen as a finite set of vectors turning around its interior wrt the trigonometric sense, and consider for any angle $\theta \in [0,\pi[$ the scalar sum of vectors that have the same direction whose argument is $\theta$ mod $\pi$, so that $f$(P) is a map whose parameter is $\theta \in [0,\pi[$ with values in $\mathbb{R}$.

For instance, if T is the triangle whose vertices are $(0;0)$, $(0;1)$ and $(1;0)$ then

$f$(T)($0$)$=1$, $f$(T)($\frac{\pi}{2}$)$=-1$, $f$(T)($\frac{3\pi}{4}$)=$\sqrt{2}$ and f(T)($\theta$)=0 for any other value of $\theta$.

Trivially, for any parallelogram P, $f$(P) is the null function. Is it true that for any polygon P such that $f$(P) is the null function, P is a finite disjoint set of parallelograms? I think the result is yes, but I am not yet able to prove it.

My first thought was to try an induction on $\frac{n}{2}$ where $n$ is the number of sides of P, but I have realized then that it is not so clear that f(P) cannot be the null function when the number of sides of P is odd... thanks in advance for your comments.