It is shown in section $1.3$ of ug level book on Group Theory by Louis W. Shapiro, a way to build up the possible multiplication tables for groups of order $4$.

I know three properties only, as stated below (also, the reason other posts are unhelpful):

1. In abelian groups, if $ab=c$, then $ba =c$. This implies that their group tables must be symmetrical about the diagonal.

2. If take $ab=a$, then $b=e$; which is wrong.

3. In a group table, it is not possible to have $ab=ac=d$, as it implies $b=c$. Similarly, not possible to have $ba = ca = d$.

The book states two cases based on the choice of $ab = e$, or $ab = c$.

Case I: $ab = e$

$$\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} & e&a&b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&&& \\ \textbf{b} &b&&&\\ \textbf{c}&c&&&\end{array}\right]$$

$$\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} & e&a&b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&&e& \\ \textbf{b} &b&&&\\ \textbf{c}&c&&&\end{array}\right]$$

$$\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} &e &a&b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&c&e&b \\ \textbf{b} &b&&&\\ \textbf{c}&c&&&\end{array}\right]$$

$$Case \ I :\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} &e &a&b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&c&e&b \\ \textbf{b} &b&e&c&a\\ \textbf{c}&c&b&a&e\end{array}\right]$$

Doubt -1: This is an abelian group, as per the property (#$1$) stated above.

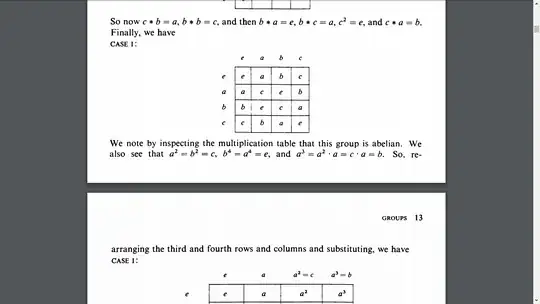

The abelian property of the group is corroborated in the book, as shown in the image below.

But, the diagonal elements in the group table are not identity elements.

Also, no swap of rows / columns can achieve the diagonal elements being identity here.

Case II: $ab = c$

$$\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} & e &a &b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&&c& \\ \textbf{b} &b&&&\\ \textbf{c}&c&&&\end{array}\right]$$

$$\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} & e &a &b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&&c&b \\ \textbf{b} &b&&&\\ \textbf{c}&c&&&\end{array}\right]$$

$$Case \ II \ (a) :\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} & e &a &b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&e&c&b \\ \textbf{b} &b&c&e&a\\ \textbf{c}&c&b&a&e\end{array}\right]$$

Doubt -2:

Book states (in table - Case II(a)) only one choice for $ac=b$, but it is not clear why $ac =e$ could not be a choice.

So, select the option $ac=e$ instead to see what changes it brings:

$$\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} & e &a &b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&&c&e \\ \textbf{b} &b&&&\\ \textbf{c}&c&&&\end{array}\right]$$

$$\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} & e &a &b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&b&c&e \\ \textbf{b} &b&&&\\ \textbf{c}&c&&&\end{array}\right]$$

$$\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} & e &a &b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&b&c&e \\ \textbf{b} &b&c&&\\ \textbf{c}&c&e&&\end{array}\right]$$

$$Case \ II \ (b) :\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} & e &a &b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&b&c&e \\ \textbf{b} &b&c&e&a\\ \textbf{c}&c&e&a&b\end{array}\right]$$

Doubt -3:

Case II (c) : It is stated in the book, for Case II, that had we chosen $bc=e$, then would have reverted back to case I.

I want to ask, how does it become case I.

$$\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} & e &a &b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&e&c&b \\ \textbf{b} &b&&&e\\ \textbf{c}&c&&&\end{array}\right]$$

As not detailed further in the book, tried to fill the rest of the table as shown below:

No choice apart from $ba=c$, also no choice apart from $bb=a$.

$$\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} & e &a &b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&e&c&b \\ \textbf{b} &b&c&a&e\\ \textbf{c}&c&&&\end{array}\right]$$

Similarly, the last row has restrictions as no choice apart from $ca=b$; $cb=e$.

$$Case \ II \ (c) :\left[\begin{array}{c|cccc}* & \textbf{e} & \textbf{a} & \textbf{b} & \textbf{c}\\ \hline \textbf{e} & e &a &b&c \\ \textbf{a} &a&e&c&b \\ \textbf{b} &b&c&a&e\\ \textbf{c}&c&b&e&a\end{array}\right]$$

But, it is unclear how the substitution has made the table like that of Case I.