In my lectures notes, the definition of topological manifold is as follows:

A topological space $(X,\tau)$ that is connected, T2 and locally euclidean with a countable basis is called a topological manifold if $(A,\psi_1)$, $(B,\psi_2)$ are charts such that $A \cap B \neq \phi$ .

My question is about the countable basis,

1)is it referred to the locally euclidean space or to the whole $(X,\tau)$? I mean, are they talking about the basis of the domain of each chart, or about the whole space?

2) why should it be countable? Could you provide an example?

Please stick to topological manifolds, I've only seen this definition as the final part of a general topology course, I've seen some posts about, but they give examples that are too technical to understand, I would like a simple reason/example base on introductory general topology stuff

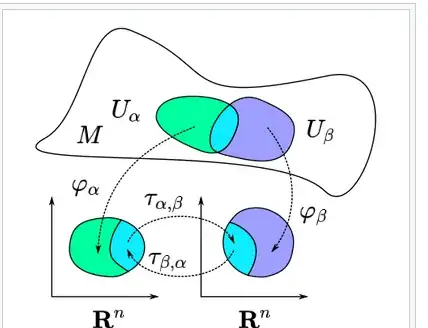

In particular, I would like to know if dropping the countability requirement affects the transition function $\tau_{\alpha, \beta}$ or the homeomorphisms $\varphi_\alpha$ ,$\varphi_\beta$ in the following scheeme?