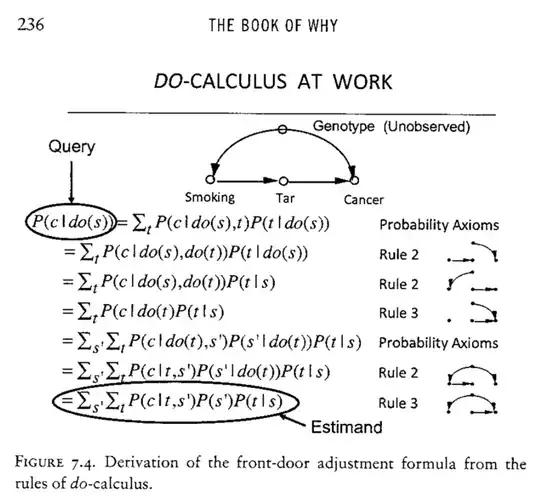

I have a number of related questions about the derivation of the front-door adjustment formula as given on page 236. Here is the derivation. I would have typed it up, but the diagrams at the far right would have been a pain to include.

There is a typo in Line 4, caught in the errata. It should be

$$=\sum_t P(c|\operatorname{do}(t){\color{red})}\,P(t|s). $$

Some additional background are the Rules of the Do-Calculus, which are as follows:

Rule 1. Assume the variable set $Z$ blocks all paths from $W$ to $Y$ after we have deleted all arrows leading into $X.$ Then $$P(Y|\operatorname{do}(X),Z,W)=P(Y|\operatorname{do}(X),Z). $$

Rule 2. If $Z$ blocks all back-door paths from $X$ to $Y,$ then $$P(Y|\operatorname{do}(X),Z)=P(Y|X,Z). $$

Rule 3. If there are no causal paths from $X$ to $Y,$ then $$P(Y|\operatorname{do}(X))=P(Y). $$

My questions are as follows:

Given the invocation of the Probability Axioms in Line 1, it is not difficult to follow the validity of the same invocation in Line 5. However, which axiom is being used, here? Where can I find a discussion of it?

In Lines 2, 3, 4, 6, and 7, Pearl invokes Rule 2 or 3. Next to the invocation is a diagram, which is supposed to be some subset of the original at the top, involving a stereotypical confounding unobserved variable situation. Why can Pearl just delete edges at will? That is, how come the expressions are equivalent while he's manipulating the diagram right and left?

The final result has $s$ and $s'$ in it, but the version of the Front-Door Adjustment Formula on page 227 does not: $$P(Y|\operatorname{do}(X))=\sum_z P(Z=z|X) \sum_x P(Y|X=x,Z=z) P(X=x). \quad \text{(7.1)} $$ Here $z$ is like $t$ in the formula above, as well as $x\to s$ and $y\to c.$ How has he proved the formula on page 227? Wouldn't he have to collapse $s'\to s$ to finish?

Thank you for your time!

- Why isn't the expression this instead: $$P(c|\operatorname{do}(s))=\sum_t P((c|\operatorname{do}(s))|t),P(t)?$$

- So, e.g., in Line 2 of the derivation, what would $Z$ be?

- I'm afraid you haven't answered this one at all. I know why someone would put $s'$ in there instead of $s.$ What I'm asking is this: it doesn't appear to me that he has proved the Front-Door Formula, because the Front-Door Formula doesn't have different $s$'s in it, at least not the version on page. 227. Is he just being sloppy?

– Adrian Keister Feb 25 '20 at 18:43