Here's an approach that starts at the point $(a, f(a))$ of intersection of degree $1$, rather than at the point $(x_T, f(x_T))$ at which the line is tangent.

Rescaling (changing coordinates by $(x, y) \rightsquigarrow (\tilde x, \tilde y) = (\lambda x, \lambda y)$, $\lambda > 0$), reflecting across the $x$-axis ($(x, y) \rightsquigarrow (-x, y)$) and translating ($(x, y) \rightsquigarrow (x - h, y + k)$ for constants $h, k$) preserve tangency and orthogonality of curves, so we may use the freedom of those coordinate changes to reduce the problem to the case $$f(x) = x^3 - C x .$$

Now, the line orthogonal to the graph of $f$ at $x = a$ is the graph of

$$O(x) = f(a) - \frac{1}{f'(a)} (x - a) = a^3 - C a - \frac{x - a}{3 a^2 - C}$$ (except, if $C > 0$, where $a = \pm \sqrt\frac{C}{3}$, where the line is vertical, and hence does not intersect the graph of $f$ anywhere else).

Now, $f$ and $O$ have an intersection of multiplicity $1$ at $(a, f(a))$, so $O$ is tangent to $f$ if and only if $f - O$ has a multiple root. But a polynomial has a multiple root iff its discriminant $\Delta$ is zero. By construction, $f - O$ is a depressed cubic (that is, its quadratic coefficient is zero, so that it has the form $x \mapsto x^3 + p x + q$), so $$\Delta = -4 p^3 - 27 q^2 = \frac{[9 a^4 - 15 C a^2 + (4 C^2 + 4)][9 a^4 - 6 C a^2 + (C^2 + 1)]}{(-3 a^2 + C)^3} .$$

The second factor in the numerator is $(3 a^2 - C)^2 + 1 > 0$, so $\Delta = 0$ iff $$\phantom{(ast)} \qquad 9 a^4 - 15 C a^2 + (4 C^2 + 4) = 0 . \qquad (\ast)$$

(Solutions $(C, a)$.)

If $C < 0$, then the left-hand side is $(3 a^2)^2 + (\sqrt{- 15 C} a)^2 + 4 C^2 + 4 > 0,$ so there are no solutions---this recovers exactly the necessary condition $C \geq 0$ on the discriminant observed in the question statement (and specialized to our normal form for $f$).

Now, $(\ast)$ is a biquadratic equation in $a$, and completing the square in $a^2$, rearranging, and clearing denominators gives the equivalent equation

$$(6 a^2 - 5 C)^2 = 9 C^2 - 16 .$$

We can now directly solve for $a$ as a function of $C$. In particular, we see that a necessary (and, one can see directly, sufficient) condition for the existence of a line satisfying the criteria is $C \geq \frac{4}{3}$. Moreover, we can see that:

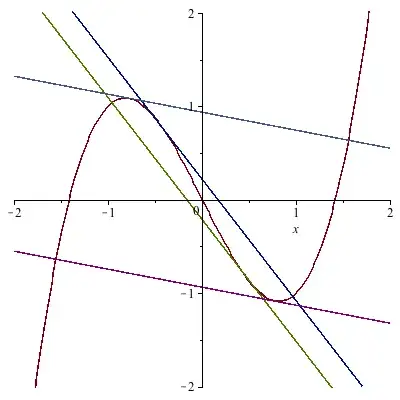

- If $C > \frac{4}{3}$ there are four solutions, given by

$$a = \pm \frac{1}{6} \sqrt{30 C \pm' 6 \sqrt{9 C^2 - 16}} .$$

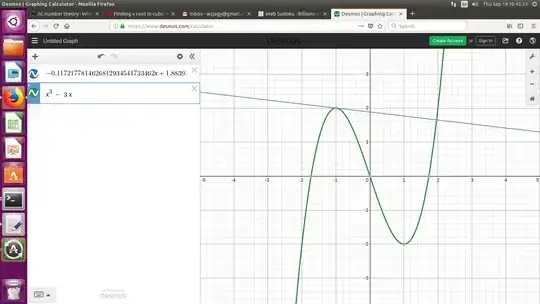

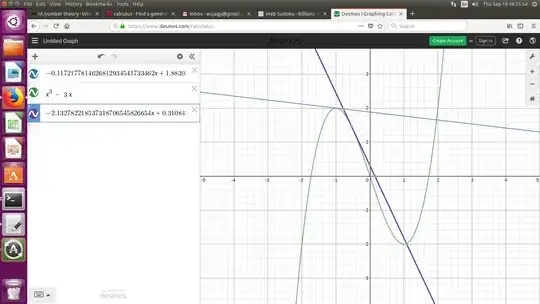

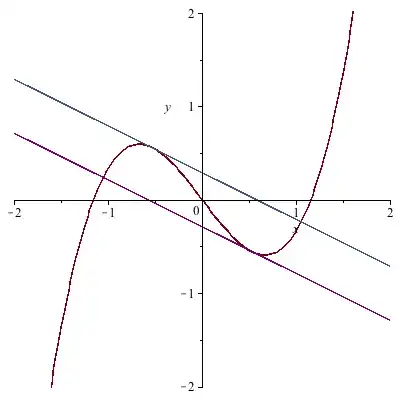

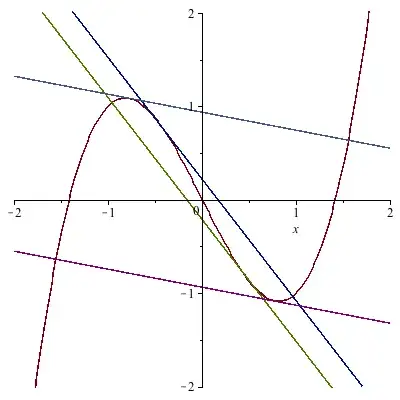

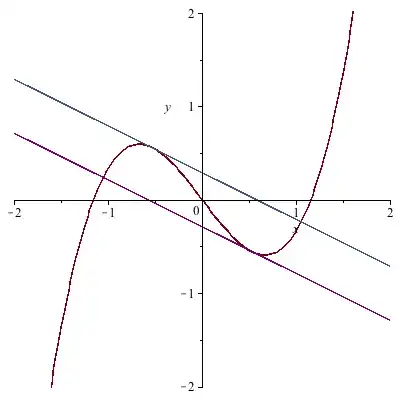

(Typical generic case, $C = 2$)

- In the critical case $C = \frac{4}{3}$ there are two solutions,

$$a = \pm \frac{\sqrt{10}}{3} .$$

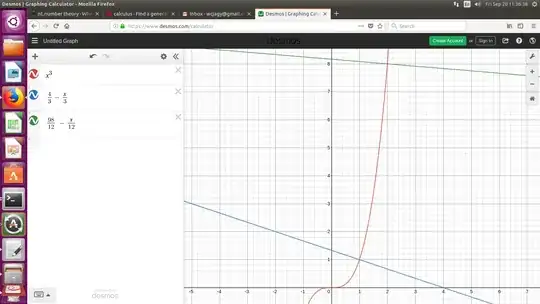

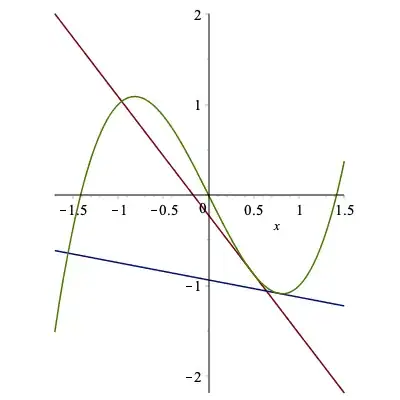

(Critical case, $C = \frac{4}{3}$.)

Remark 1 Applying as appropriate a reflection, a rescaling, and a translation to bring the general form $f(x) = a x^3 + b x^2 + c x + d$ to our normal form $f(x) = x^3 - C x$, we see that the condition $C \geq \frac{4}{3}$ for the existence of solutions corresponds to the inequality $b^2 - 3 a c \geq 4 |a|$, which again is strictly stronger than the condition $b^2 - 3 a c \geq 0$ in the original question statement.

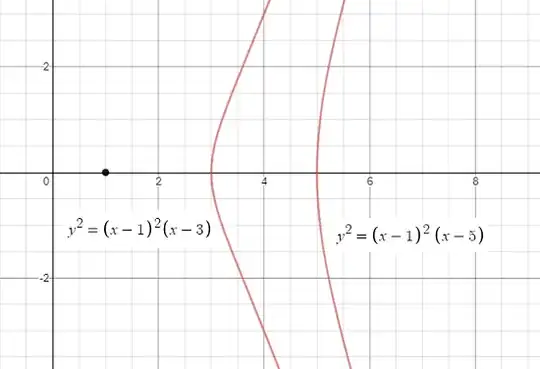

Remark 2 An interesting feature of this situation is that as $C \to \infty$, the horizontal spacing of the four orthogonal intercepts approaches $1 : 2 : 1$, and since this ratio is preserved by the applied transformations, the conclusion also applies to $f$ of the general form. Indeed, the asymptotic behaviors of the four solutions are

$$\pm \sqrt{\frac{C}{3}}, \quad \pm 2 \sqrt{\frac{C}{3}} \pmod {O(C^{-3 / 2})} .$$