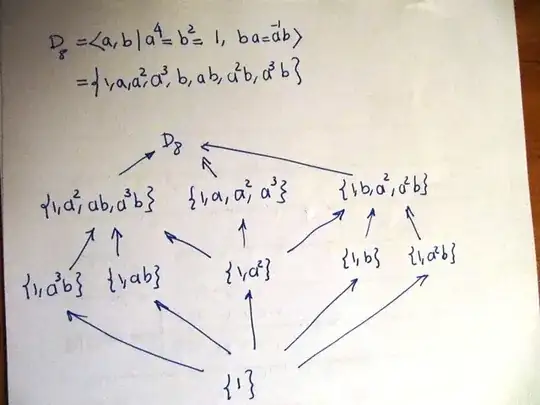

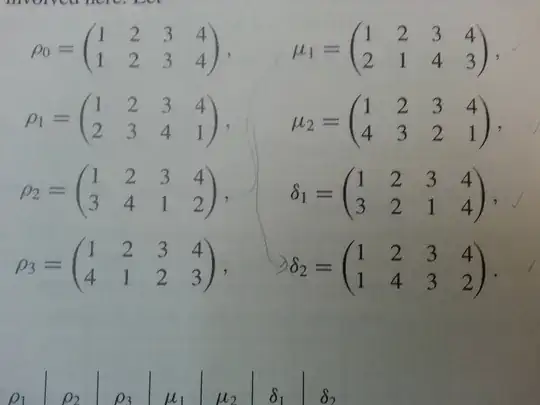

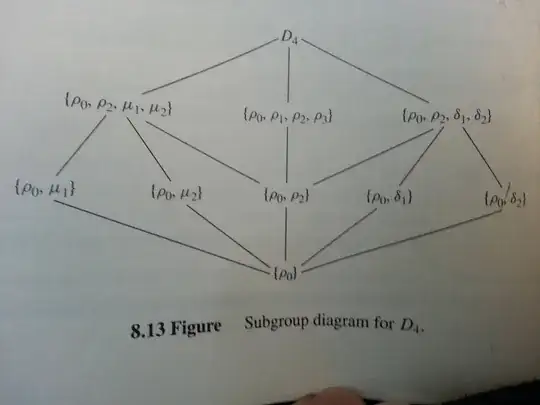

I am reading Fraleigh p. 80 in A First Course in Abstract Algebra, and in the book i see the elements and subgroup diagram of the dihedral group $D_4$. Here are they:

Here is how i try to draw the subgroup diagram: p0 must be included in every subgroup since it is identity element. Then i look at p1, and try to find the subgroups including p1, since p1 is included, the inverse of it must be included also, and p1op1 must be included also, and so on . I need to check whether the result of these computations make it closed. But this lookslike a very long process. Is there an easy way to do that? For example, by looking at u1 can we immediately say that it is included or not in a subgrouo without checking all compositions of u1 with u1? Or by looking at p1 can we find < p1 > easily? Thanks