tl;dr (written after addendum): It seems plausible that $A$ contains points of both signs having arbitrarily large magnitudes. It's not so clear $A$ is dense outside of a neighborhood of zero.

Suppose that $\varepsilon = \left| \dfrac{\pi}{2} - \dfrac{n}{k} \right|$ is small, so that $n$ is nearly $k \pi/2$. If $k$ is even, $\dfrac{\tan n}{n}$ is small. If $k$ is odd, $\dfrac{\tan n}{n}$ is large. Dirichlet's approximation theorem tells us there are infinitely many $n,k$ pairs with $\varepsilon < \dfrac{1}{k^2}$.

By applying Dirichlet's approximation theorem to $\pi$, and arguing that this new set of pairs is a subset of the above set of pairs, we find there are infinitely many even $k$. But we do not know if there are infinitely many odd $k$.

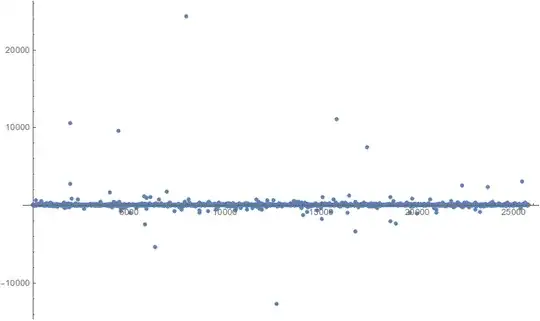

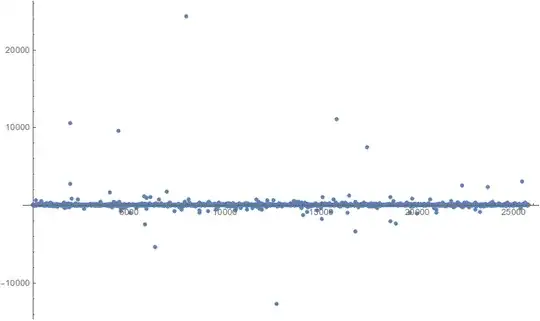

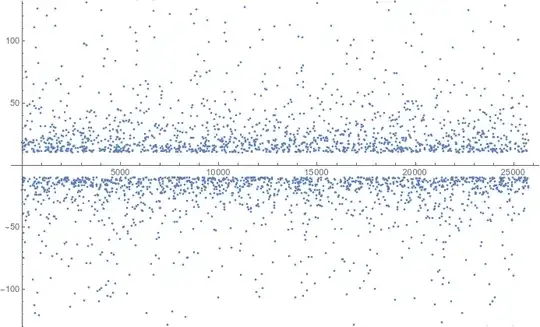

Using the first $50\,000$ convergents of the continued fraction for $\pi/2$ as $\dfrac{n}{k}$ pairs, and plotting $\left( \log_{10} n,\dfrac{\tan n}{n} \right)$, we have

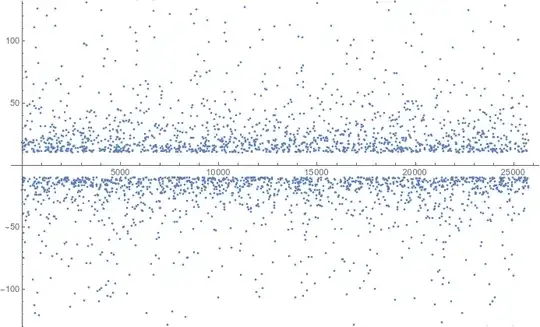

and zooming in the vertical axis a bit

there do seem to be large magnitude outliers and no tendency to collapse towards zero, at least up to $n$ near $10^{25\,000}$. (Note that values of $\left| \dfrac{\tan n}{n} \right| <10$ are suppressed to avoid a solid band of points obscuring the horizontal axis.)

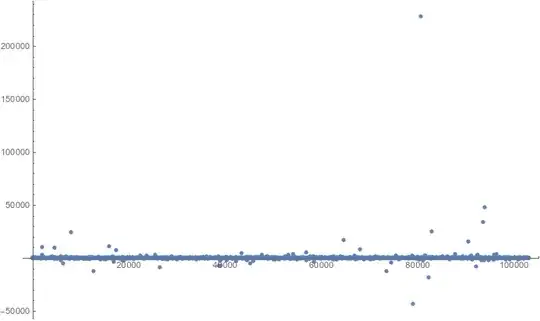

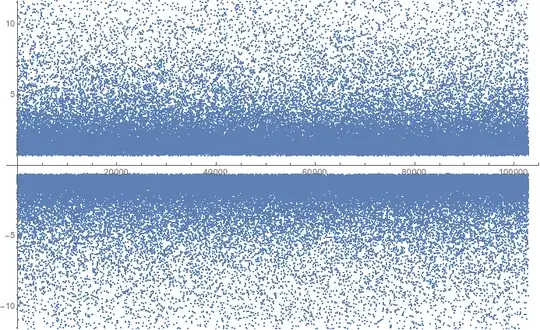

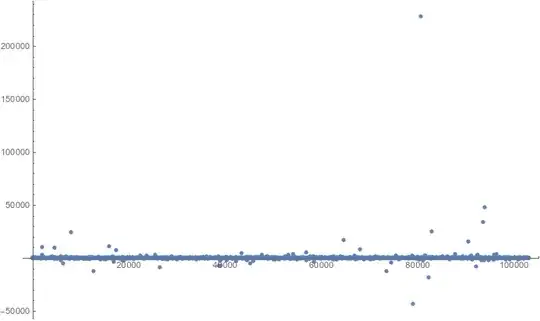

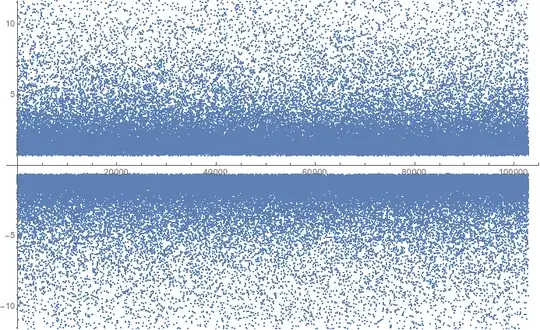

Extending a bit further, to the first $200\,000$ convergents... These only plot points for odd $k$, which is $133\,363$ of the convergents (so maybe there is a significant bias toward odd $k$s).

Maybe there's a small bias favoring positive extreme values. We don't seem to run out of new extreme values. There was no need to cut out small magnitude points since we cut out even $k$s. We don't seem to be running out of odd $k$s, so maybe there are infinitely many of them. The vertical density of points seems stationary as $n$ increases. But there also seems to be very little reason to believe in eventual fill-in of the gaps between the very large magnitude points.