Given identically distributed random variables $X_1,...,X_n$, where $ \mathbb E X_i = 0$, $\mathbb E [X_i^2] = 1$, and $\mathbb E [X_i X_j] = c<1$, define $S_n = X_1 + ... + X_n$. Will

$$\frac{S_n}{n} \rightarrow 0$$ in probability as $n\rightarrow \infty$?

The closest question I could find is this one, where an additional constraint is placed on the covariances, such that Chebyshev inequality can be used to bound $\left|\frac{S_n}{n} \right|$ by $\text{Var}\left(\frac{S_n}{n}\right)$. However, in my case $\text{Var}\left(\frac{S_n}{n}\right)$ is constant, so this approach will not work.

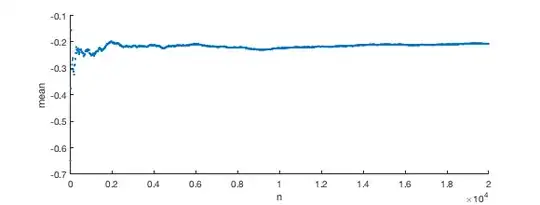

Indeed, when I simulate using MATLAB on an example where I generate Gaussian random variables which all have covariance $c=0.1$, I do not see it approaching zero.

rng(1)

NN =20000;

C = ones(NN,NN)*0.1 + 0.9*diag(ones(NN,1));

rndnums = mvnrnd(zeros(NN,1), C, 1);

NNs = 1:20:NN

means = -99*ones(1,length(NNs));

for ti=1:length(NNs)

means(ti) = mean(rndnums(1,1:NNs(ti)));

end

scatter(NNs ,means, '.'); xlabel('n'); ylabel('mean')

Intuitively, since all the variables are all "locked" to eachother in correlation, I can't imagine how their mean will "eventually" reach zero.

Is there a law of large numbers in this context? If so, what is the rate of convergence? Or if not, is there any way to tell what it will converge to?