I'm trying to solve the following exercise of the book "Grupos de Lie - Luiz A. B. San Martin (exercise 18, page 55)":

Exercise: Let $G$ be a topological group (if necessary, $G$ is Hausdorff) and $H_1 \subset H_2\subset G$ closed subgroups of $G$. Show that if $G/H_2$ and $H_2/H_1$ are compact, then $G/H_1$ is compact.

Some comments...

It is easy to see that the function \begin{align*} \pi: G/H_1 &\to G/H_2 \\ g H_1 & \mapsto g H_2, \end{align*} is a continuous and open function, nevertheless $\pi$ also satisfies $g_1 \cdot \pi(g_2) = \pi(g_1\cdot g_2)$, $\forall \ g_1 \in G,\ $ ($g_1 \cdot (g_2 H) = (g_1 \cdot g_2) H$).

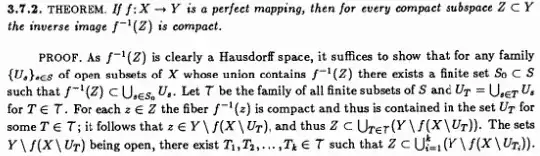

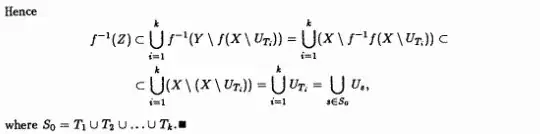

Although I am aware of the following theorem:

Theorem: Let $G$ be a topological group, and $H$ a closed subgroup of $G$, if $H$ and $G/H$ are compact then $G$ is compact.

I can't apply it to solve my problem, once neither $G/H_1$ nor $H_2/H_1$ are topological groups.

So, I tried to adapt the proof of the theorem cited above for my case, and it is necessary to show that the function $ \pi $ is a closed function, which I was not able to conclude.

Can anyone help me?