The question's already been answered in the comments, but for posterity there should be an official one.

The answer is No and a nice counterexample is

$$ 0 \to \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z}/2 \to 0$$

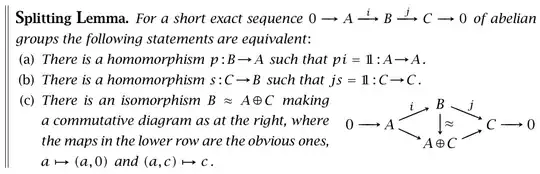

We know this can't split because the Splitting Lemma would then imply $\mathbb{Z} \cong \mathbb{Z} \oplus \mathbb{Z}/2$, which is a contradiction because $\mathbb{Z}$ has no torsion.

It is true that in the category of Sets every surjective function has a right inverse and every injective function has a left inverse, but this is not true in the category of Abelian Groups. Indeed a right inverse $\mathbb{Z}/2 \to \mathbb{Z}$ of the quotient map would be any function sending $0$ to an even number and $1$ to an odd number, but this can never be a homomorphism, again because $\mathbb{Z}$ has no torsion.