I was told that an antiderivative doesn't represent any area, it is just a family of functions, but today I noticed something quite interesting thing:

If we have $f(x)=2x$, then $F(x)=x^2+C$. The area under $f(x)$ from $0$ to $1$ is $1$, and $F(1)$ is one, the area under $f(x)$ from $0$ to $2$ is $4$, and $F(2)$ is $4$, and so on.

Then I started to think, that when $C=0$, $F(x)$ is the area under $f(x)$ from $0$ to $x$, and tried some others functions like $f(x)=x^2$, $x^3$, and so on.

Then I decided to try $f(x)=\sin x$, and I failed in my guess. But then noticed, if I take $C=1$ it works! Finally, I noticed that it works in all cases when $F(0)=f(0)=0$.

So antiderivative is not only a bunch of functions but also some area?

How can I visualize it generally? How can I visualize $C$? Can this area be an endless area in both directions?

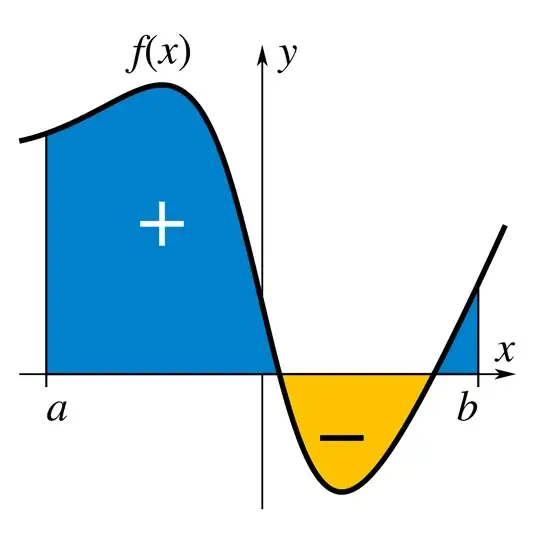

Now I study the fundamental theorem of calculus, and at first, I imagined $F(b)-F(a)$ as $(\text{area from } -\infty \text{ or } 0 \text{ to } b)-(\text{ area from }-\infty \text{ or } 0 \text{ to } a)$. Is it the right visualization?

I will be very grateful if someone could clarify my guesses. Thanks in advance

Upd: thank you all who helped me to solve my problem, i appreciate it so! To one, who faced the same question: there`s a quite similar question, and some of answers are pretty meaningful, for example, this one: https://math.stackexchange.com/a/2559329/595919