Definition. Given $a\in\mathbb R$, define the function $f_a(x)=x(\arctan x-a)$.

Definition. Given $a,b\in\mathbb R$, consider the closed set

$$

\begin{split}

E_{a,b} &= \{(x,y)\in\mathbb R^2 : x(\arctan x-a)+y(\arctan y-b)=0\} \\

&= \{(x,y)\in\mathbb R^2 : f_a(x)+f_b(y)=0\}

\end{split}

$$

Lemma 1. For every $a\in\mathbb R$, the set $[0,\infty)$ is in the image of $f_a$.

Proof. Assume $a\geq0$. Then $f_a(0)=0$ and

$$

\lim_{x\to-\infty}x(\arctan x-a)=(-\pi/2-a) \lim_{x\to-\infty}x=\infty.

$$

Since $f_a$ is continous, these limits imply the thesis. The case $a\leq0$ is analogous, with the signs changed. □

Lemma 2. If $|a|>\pi/2$, then the function $f_a:\mathbb R\to\mathbb R$ is surjective.

Proof. Assume $a>\pi/2$. We have $\pm\pi/2-a < 0$, so

$$

\lim_{x\to+\infty} x(\arctan x-a)

= (\pi/2-a)\lim_{x\to\infty} x = -\infty

$$

and

$$

\lim_{x\to-\infty} x(\arctan x-a)

= (-\pi/2-a)\lim_{x\to-\infty} x = \infty.

$$

Since $f_a$ is continuous, these limits imply that it is surjective. The case $a<-\pi/2$ is analogous. □

Lemma 3. If $|a|<\pi/2$, then

$$

\lim_{x\to\pm\infty} f_a(x) = \infty.

$$

Proof. A direct computation shows

$$

\lim_{x\to\infty} f_a(x) = (\pi/2-a)\lim_{x\to\infty}x = \infty

$$

and the same holds for $x\to-\infty$. □

Proposition. If $|a|>\pi/2$. Then $E_{a,b}$ is unbounded.

Proof. Since $f_a$ is surjective by Lemma 2, for every $y\in\mathbb R$ there exists $x\in\mathbb R$ such that $f_a(x)=-f_b(y)$. This means that $(x,y)\in E_{a,b}$. Therefore the set $E_{a,b}$ is unbounded because we can find points with arbitrary large $y$.

Proposition. If $|a|=\pi/2$. Then $E_{a,b}$ is unbounded.

Proof. Assume $a=\pi/2$. The other case is analogous. Recall the well known limit

$$

\lim_{x\to\infty} f_{\pi/2}(x) = \lim_{x\to\infty} x(\arctan x-\pi/2) = -1.

$$

For every $x$ sufficiently large we have that $f_{\pi/2}(x)\leq0$, so by Lemma 1 there exists $y\in\mathbb R$ such that $f_b(y)=-f_a(x)\in[0,\infty)$. Therefore we can find points $(x,y)\in E_{\pi/2,b}$ with arbitrary large $x$. □

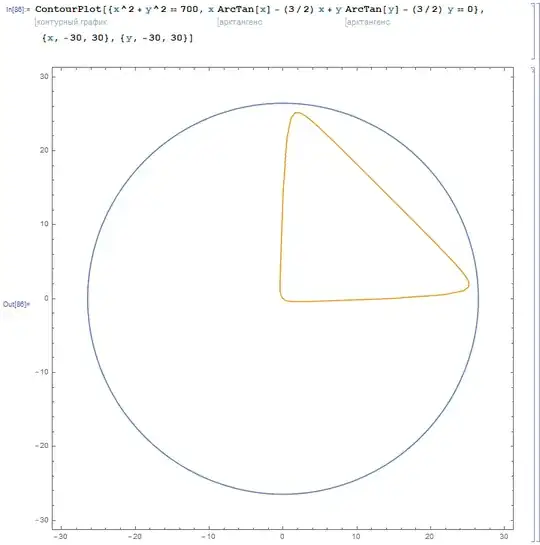

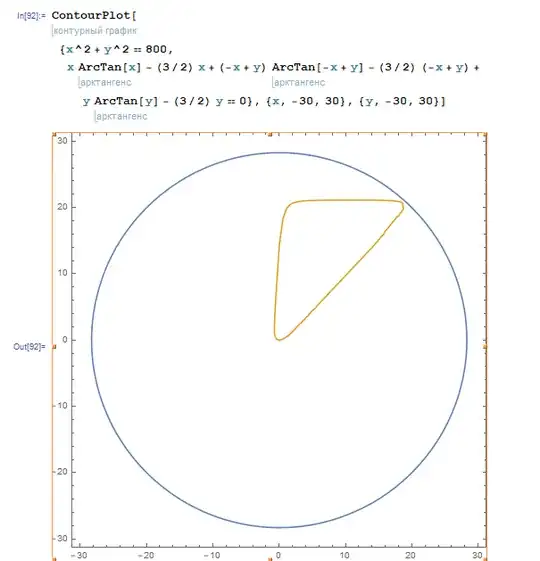

Proposition. If $|a|<\pi/2$ and $|b|<\pi/2$, then $E_{a,b}$ is bounded.

Proof. By Lemma 3, the function $f_a(x)+f_b(y)$ is coercive, meaning that $f_a(x)+f_b(y)\to\infty$ if $|(x,y)|\to\infty$, therefore its sublevel sets are bounded. In particular $E_{a,b}$ is bounded as a consequence. □

Corollary. $E_{a,b}$ is bounded if and only if $|a|<\pi/2$ and $|b|<\pi/2$.

Now, given $a,b\in(-\pi/2,\pi/2)$, how can we find an estimate on $\max_{(x,y)\in E_{a,b}} x^2+y^2$? We could try the Lagrange multipliers approach again, similarly to what we did here.

The stationary points must satisfy

$$

\bigl(f'_a(x), f'_b(y)\bigr) = \lambda (x, y) \qquad \text{for some $\lambda\in\mathbb R$},

$$

which is equivalent to

$$

\frac1{1+x^2} + \frac{\arctan x-a}x

= \frac{f'_a(x)}{x} = \lambda

= \frac{f'_b(y)}{y}

=\frac1{1+y^2} + \frac{\arctan y-b}y.

$$

Unfortunately, this time I'm not able to find a closed form solution to the system of equations

$$

\left\{\begin{array}{l}

f_a(x)+f_b(y)=0 , \\

\frac{f'_a(x)}x=\frac{f'_b(y)}y .

\end{array}\right.

$$

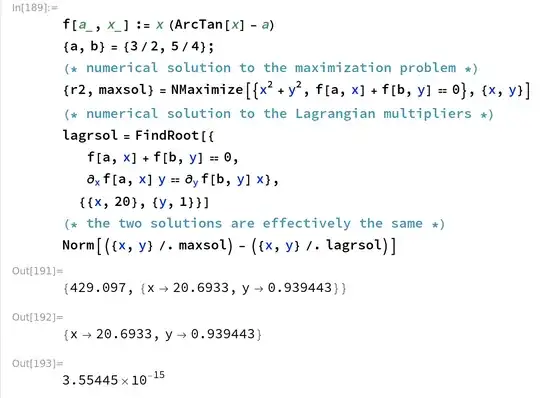

One can of course fall back to numerical solutions. I'm using Mathematica for that.

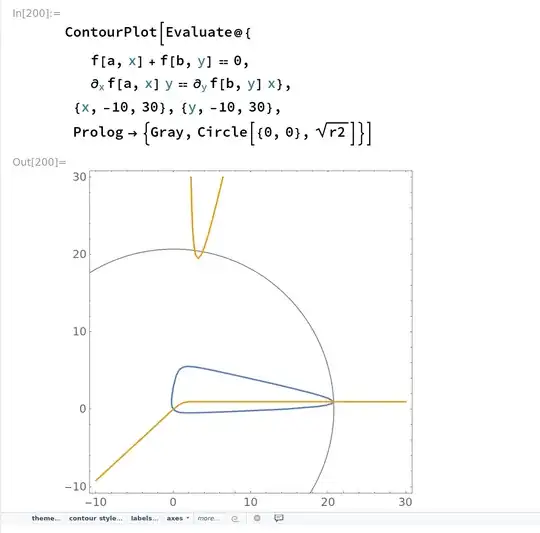

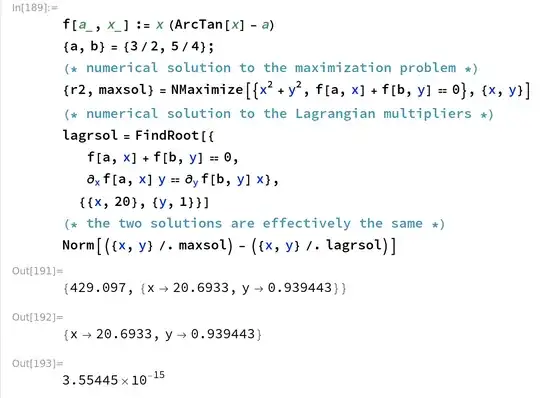

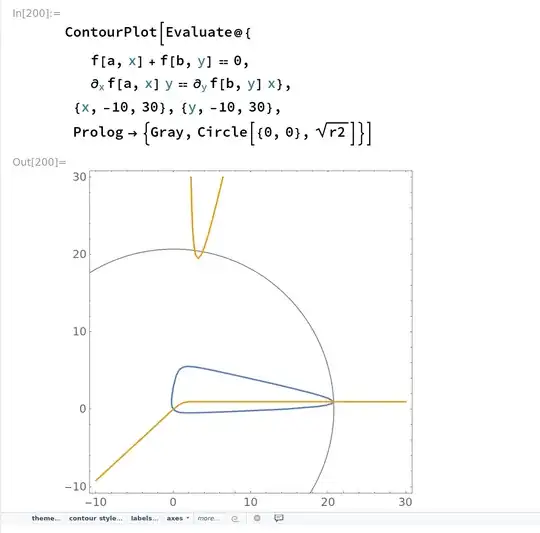

Here I fix the values $a=3/2$ and $b=5/4$, then I find extremal points numerically both with the built-in NMaximize function and by solving the Lagrange multiplier system with FindRoot. The two solutions are the same, up to machine precision. Then I plot the set $E_{a,b}$ in blue, the root locus of the Lagrange multiplier equation in orange, and the smallest fitting circle in gray.