This is an answer to half the question, which is the case for real<0. For all real(z)<0, f(z) alternates between two different values, both of which are analytic. This is because $\exp(nz)=\exp(\Re(nz))\times\exp(\Im(nz))$, and $\Re(nz)$ gets exponentially close to zero as nz gets arbitrarily large negative. It doesn't matter what $\Im(z)$ is, because zero times anything is still zero. As $\exp(nz)$ approaches arbitrarily close to zero, $(-1)^n\exp(-\exp(nz))$ approaches arbitrarily close to one for n large and even, and it approaches arbitrarily close to negative one for n large and odd. One substitution one can make is $y=\exp(z)$

$f(y)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}(-1)^n\exp(-y^n)$

This can be expanded as a taylor series, for which the first few 20 terms are listed below. notice that here, f(y=0) alternates between 1 and 0 as n goes to even infinity and 0 as n goes to odd infinity. Alternatively, the terms $a_n$ terms for the taylor series of f(y) can be used as the coefficients for a $2\pi i$ periodic complex function $f(z)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}a_n\exp(nz)$. In "y", this function has a natural boundary of the unit circle. if |y|=1, and y^n doesn't repeat in an odd cycle, and does repeat in an even cycle. This condition is met if $\Re(z)=0$ and $\frac{\Im(z)}{2\pi}$ can be expressed as a rational number in simplest form, then if the denominator is even, there ia a singularity at z. Then f(y)=f(exp(z)) gets arbitrarily large since the (-1)^n terms are cyclic instead of cancelling. So singularities are dense on the boundary of the unit circle for $f(y)$, which corresponds to singularities being dense on the imaginary axis for the $2\pi i$ periodic version of f(z). These singularities are large for $\pi i$ and $\pi i/2$ but they get fairly tame quickly. Here are the first 20 terms of the Taylor series for f(y).

f(y)= 1/2 - (1/2)*(-1)^n

+y^ 1* -1

+y^ 2* 3/2

+y^ 3* -7/6

+y^ 4* 13/24

+y^ 5* -121/120

+y^ 6* 1201/720

+y^ 7* -5041/5040

+y^ 8* 18481/40320

+y^ 9* -423361/362880

+y^10* 5473441/3628800

+y^11* -39916801/39916800

+y^12* 338627521/479001600

+y^13* -6227020801/6227020800

+y^14* 130784734081/87178291200

+y^15* -1536517382401/1307674368000

+y^16* 9589093113601/20922789888000

+y^17* -355687428096001/355687428096000

+y^18* 10679532671808001/6402373705728000

+y^19* -121645100408832001/121645100408832000

+y^20* 1338095434054579201/2432902008176640000+...

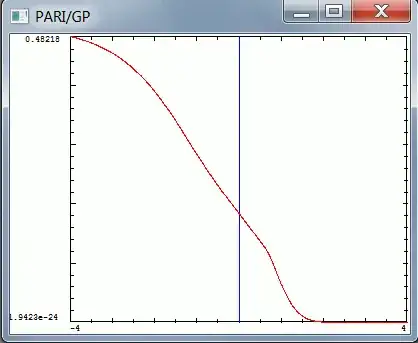

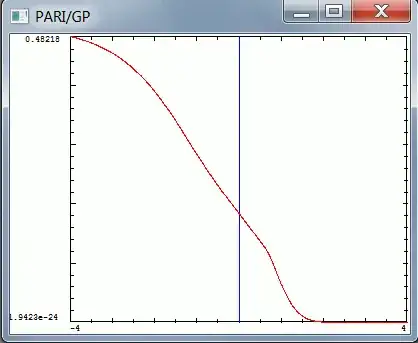

One could arbitrarily define f(z) as the average of the even and odd cases, which would make $f(z=-\infty)=1/2$. In that case, $f(0)=\frac{1}{2e}$. Here are my conjectures about the function for real(z)>0, some of which I will attempt to prove in a later post.

- for $\Re(z)>0$ the limiting value for f(z) is only defined iff $\Im(z)=2n\pi i$

- for $\Im(z)=0$ and $\Re(z)>0$, f(z) is infinitely differentiable. But f(z) does not converge to its Taylor series. At the real axis for real(z)>0, it has a radius of convergence of zero, and is nowhere analytic.

- for z=0, f(z) converges to $\frac{1}{2e}$, and has the same taylor series for both the nowhere analytic function, and the boundary of the analytic function, provided one defines the function as the average of the two analytic functions.

Plot of f(z) at the real axis:

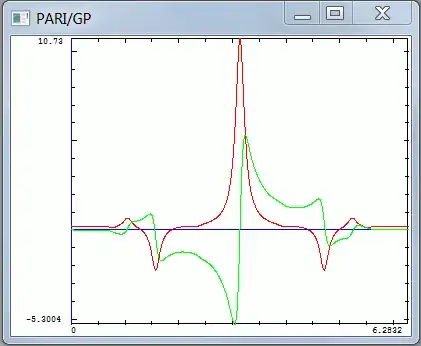

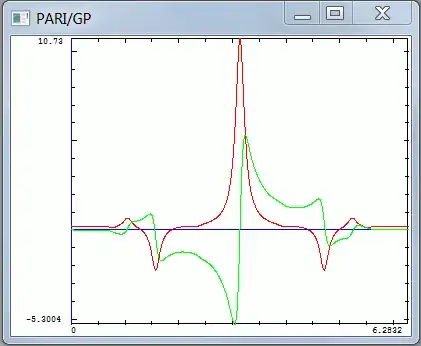

Plot of f(z) at real(z)=-0.1, from imag(z)=0 to imag(z)=2Pi, showing the influence of nearby singularities, at $\pi i$, $\frac{\pi i}{2}$, $\frac{3\pi i}{2}$. Red is real and green is imaginary.