My textbook has a very brief section that introduces some concepts from measure theory:

Another technical detail of continuous variables relates to handling continuous random variables that are deterministic functions of one another. Suppose we have two random variables, $\mathbf{x}$ and $\mathbf{y}$, such that $\mathbf{y} = g(\mathbf{x})$, where $g$ is an invertible, continuous, differentiable transformation. One might expect that $p_y(\mathbf{y}) = p_x(g^{−1} (\mathbf{y}))$. This is actually not the case.

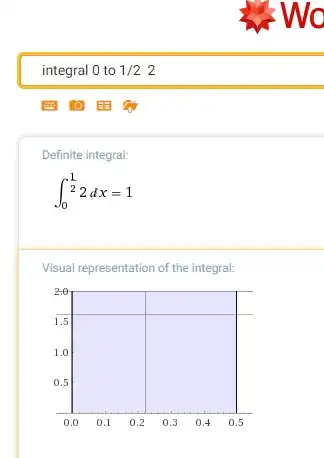

As a simple example, suppose we have scalar random variables $x$ and $y$. Suppose $y = \dfrac{x}{2}$ and $x \sim U(0,1)$. If we use the rule $p_y(y) = p_x(2y)$, then $p_y$ will be $0$ everywhere except the interval $\left[ 0, \dfrac{1}{2} \right]$, and it will be $1$ on this interval. This means

$$\int p_y(y) \ dy = \dfrac{1}{2},$$

which violates the definition of a probability distribution. This is a common mistake. The problem with this approach is that it fails to account for the distortion fo space introduced by the function $g$. Recall that the probability of $\mathbf{x}$ lying in an infinitesimally small region with volume $\delta \mathbf{x}$ is given by $p(\mathbf{x}) \delta \mathbf{x}$. Since $g$ can expand or contract space, the infinitesimal volume surrounding $\mathbf{x}$ in $\mathbf{x}$ space may have different volume in $\mathbf{y}$ space.

To see how to correct the problem, we return to the scalar case. We need to present the property

$$| p_y(g(x)) \ dy | = | p_x (x) \ dx |$$

Solving from this, we obtain

$$p_y(y) = p_x(g^{-1}(y)) \left| \dfrac{\partial{x}}{\partial{y}} \right|$$

or equivalently

$$p_x(x) = p_y(g(x)) \left| \dfrac{\partial{g(x)}}{\partial{x}} \right|$$

How do they get $p_y(y) = p_x(g^{-1}(y)) \left| \dfrac{\partial{x}}{\partial{y}} \right|$ or equivalently $p_x(x) = p_y(g(x)) \left| \dfrac{\partial{g(x)}}{\partial{x}} \right|$ by solving $| p_y(g(x)) \ dy | = | p_x (x) \ dx |$?

Can someone please demonstrate this and explain the steps?