I have an 8 dimensional dataset (as an Nx8 matrix), and I am hypothesising that much of the dataset can be described simply by linear addition of two known non-orthogonal vectors (i.e. two 1x8 vectors).

As a result I want to project the data onto a skew coordinate system which lies on a 2D plane embedded within the larger 8-D space.

If the two vectors are orthogonal I am aware that it is a simple matrix multiplication of the Nx8 matrix by the 2x8 matrix (the two vectors together).

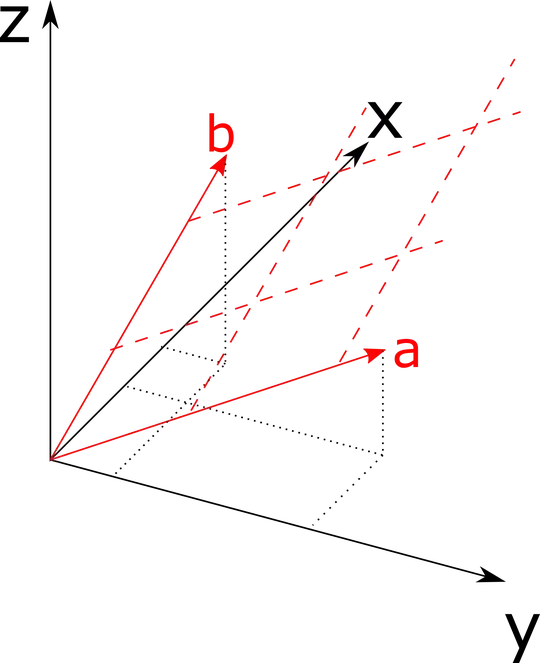

For example consider the 3D simplification shown below. My data is analagously described by a Nx3 matrix along the x,y & z axes. However I want to project into onto the 3D skew coordinate system in red, described by the known vectors a and b.

My two questions are:

My two questions are:

1) What is the analogous operation to project the 8D data onto a skewed 2D coordinate system?

2) If I perform the matrix multiplication described above with the non-orthogonal vectors what is the geometrical interpretation of the resultingNx2 matrix?