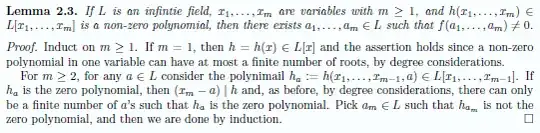

As the title states, I'm trying to prove the nontrivial implication, that is, if $p \in \mathbb{k}[X_1, \dots , X_n]$ is such that $p(x) = 0$ for all $x \in \mathbb{k}^n$ and $\mathbb{k}$ is infinite, then $p = 0$.

My idea is to do induction in the number of variables, but I'm not sure on how to proceed. For the base case, since $\mathbb{k}$ is infinite, $p$ having an infinite amount of roots would imply $x-r | p$ for infinitely many $r$. Thus, $p$ cannot be non-null, because it would have finite degree and so a bounded amount of roots.

Fixing a variable to be zero, the polynomial $p(0, \dots, X_n)$ on $n-1$ variables is zero as a a function, and so by an inductive reasoning it should be the zero polynomial. Thus, all coefficients of terms that do not contain $X_1$ must be zero. Doing this with each variable, the only possible terms to be nonzero are the ones that have all variables.

Can I finish this argument by an additional convenient evaluation on $p(X_1 \dots X_n)$? An immediate requirement is for the coefficients to 'remain separate' (e.g. $p(t, \dots ,t)$ is the zero function and so as a polynomial it is zero, but its coefficients are linear combinations of the original one, so I still can say that the original coefficients are themselves zero.).