The algebraic reason for the form of the sum in the trapezoid method is that a single trapezoid in that method has two base lengths: $f(x_i)$ on the left and $f(x_{i+1})$ on the right. Its height (measured horizontally, because in a trapezoid the "height" is always the distance between the parallel sides) is $h = \frac{b-a}n.$ Hence its area is

$$

\frac12 h(f(x_i) + f(x_{i+1}))

= \frac{b-a}n\left(\frac12 f(x_i) + \frac12 f(x_{i+1})\right).

$$

When the areas of two adjacent trapezoids are added, the result is

\begin{multline}

\frac{b-a}n\left(\frac12 f(x_i) + \frac12 f(x_{i+1})\right) +

\frac{b-a}n\left(\frac12 f(x_{i+1}) + \frac12 f(x_{i+2})\right) \\ =

\frac{b-a}n\left(\frac12 f(x_i) + f(x_{i+1}) + \frac12 f(x_{i+2})\right).

\end{multline}

That is, the term $f(x_{i+1})$ comes from the sum of two copies of the term $\frac12 f(x_{i+1}).$

Add up the areas of all of the trapezoids, and all the terms will simplify in this way except for the first and last terms.

But we can also interpret this geometrically.

Consider a single trapezoid from the trapezoid method. We can dissect the trapezoid and rearrange the pieces into two half-width rectangles as shown in the figure below.

On the left side of the figure, the shaded region is the original trapezoid.

On the right side, the shaded region comprises the two half-width rectangles.

To get from the left-hand shape to the right-hand shapes, we cut the triangle labeled $A$ out of the trapezoid and paste it into the region labeled $B.$

Now let's do that for each of the trapezoids in a trapezoid-method integral.

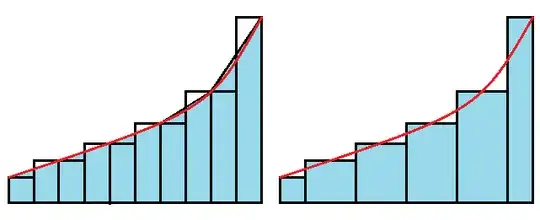

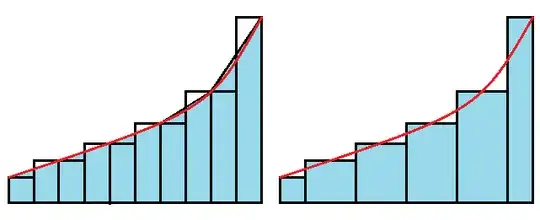

On the left side of the figure below, the shaded region comprises all the trapezoids from the trapezoid method. We cut out the shaded triangles and use them to fill the unshaded regions.

This produces many half-width rectangles, but most of the rectangles come in pairs of equal height. If we then erase the line separating each pair of equal-height rectangles, we get the arrangement of rectangles on the right side of the figure.

Now look at the rectangles on the right side of the figure. The leftmost rectangle is one half of the leftmost rectangle of the "left" Riemann sum and the rightmost rectangle is one half of the rightmost rectangle of the "right" Riemann sum.

The other rectangles could be the last $n - 1$ rectangles of the "left" sum shifted half their width to the left, or they could be the first $n - 1$ rectangles of the "right" sum shifted half their width to the right.

But the entire area of the rectangles on the right-hand side is exactly the area of the trapezoids on the left-hand side, merely with a finite number of pieces rearranged.