Here's a proof that if a triangle's vertices' coordinates are integers, then it is not equilateral.

Suppose that such a triangle $ABC$ were equilateral, with every side of length $l$, and with $l$ minimal given these conditions. If $4\mid l^2$ then all the $x$-coordinates have the same parity, and all the $y$-coordinates have the same parity, so we may translate $ABC$ if necessary so that all the coordinates are even, then shrink it linearly by a factor of $2$, contradicting minimality of $l$.

So $4\nmid l^2$.

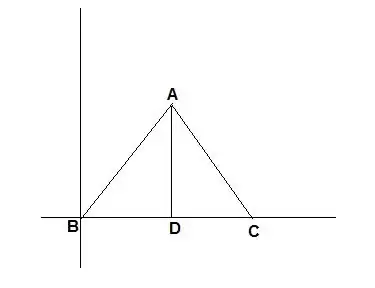

By the pigeonhole principle, at least two of the vertices have $x$-coordinates of the same parity. Pick two such and label them $A$ and $B$, and the other vertex $C$. Likewise, at least two of the vertices have $y$-coordinates of the same parity. If $A$ and $B$ were such, then $4\mid l^2$, which has been shown to be false. So wlog $A$ and $C$ have $y$-coordinates of the same parity. Then $|BC|^2$ is even but $|AB|^2$ and $|AC|^2$ are odd, so $ABC$ is not equilateral.

Alternative proof

Again suppose $l$ minimal. Chequer the lattice points. If $l^2$ is odd, every two vertices have different colours. But, by the pigeonhole principle, at least two must have the same colour. So $l^2$ is even, so all vertices have the same colour, and thus lie on the coarser lattice of points of that colour. Thus a linear transform $\mathbf{T}$ may be applied which maps this coarse lattice onto the original. $\mathbf{T}$ rotates by $45^\circ$, preserves angles and halves areas, yielding a smaller example. This contradicts minimality of $l$.