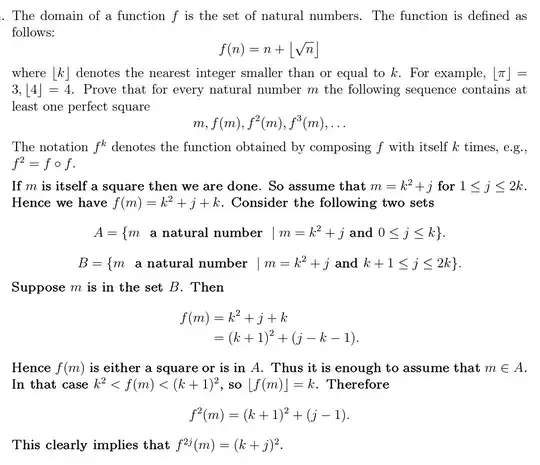

- At one point, it says, Thus it is enough to assume $m\in A$. Is that correct? I think they meant $f(m)$ instead of $m$.

- Secondly, there's another error where they claim $\lfloor f(m) \rfloor =k$. It's supposed to be $\left\lfloor \sqrt f(m) \right\rfloor =k$

DOUBTS :

- In the very last line they say This clearly implies that $f^{2j}= (k+j)^2$ but I don't find it quite trivial. Can "you" please explain this part?

I think that the floored part is $k$, then, $k+1$, then $k+2$, $\cdots$. But then $f^{2j}$ doesn't come similar to theirs.