Here is another way without the use of coordinates, 'adapted' and expanded from the proof of Hartshorne's Theorem II.8.19.

Let $U\subset X$ be the largest open subset for which there is a morphism $f:U\to Y$ representing the birational map.

Let $P\notin U$ be a point.

Since $X$ is irreducible of dimension 1, the only non-closed point is the generic point, which must be contained in $U$.

In other words, $P$ has to be closed, of codimension 1.

By the regularity of $X$, $\mathcal O_{P,X}$ is a regular local ring of dimension 1, so it is a valuation ring.

Let $K$ be its field of fractions.

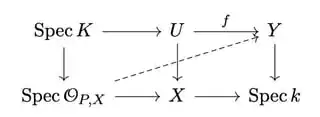

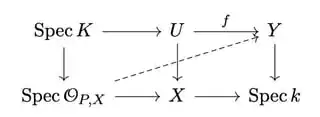

We have the commutative diagram, where $\operatorname{Spec} K\to U$ is the generic point.

Since $Y$ is projective, in particular, proper, there exists a unique dashed morphism as such.

Since the diagram commutes, the dashed map $g$ is compatible with the original birational map $f$. (They coincides at the generic point.)

Take an open affine neighborhood $V=\operatorname{Spec}A$ of $g(P)\in Y$, also an open affine neighborhood $U=\operatorname{Spec}B$ of $P\in X$.

Then $g$ is locally a $k$-algebra homomorphism $\varphi:A\to \mathcal O_{P,X}$, where $\mathcal O_{P,X}=B_P$.

Since $Y$ is of finite type over $k$, $A$ is a finitely generated $k$-algebra.

Suppose the generators are $a_1,\ldots,a_n\in A$, we may write $\varphi(a_i)=b_i/s_i$ for $b_i,s_i\in B$ and $s_i\notin P$.

Let $s=s_1\cdots s_n$. Then $\varphi$ restricts to a map $A\to B_s$, which corresponds to a morphism of schemes $D(s)\to V$.

Again since this map is the same as the given $f$ at the generic point, there exists some open $Z$ such that $g\vert_Z=f\vert_Z$, which contradicts the maximality of $U$. Thus $U=X$.

Similarly, we may prove that $Y\to X$ is a regular map, and hence $X$ and $Y$ are isomorphic.

Then a rational map $U \subset X \to \mathbb{P}^N$ will be of the form $x \mapsto [f_0(x):\ldots :f_N(x)]$ with $f_j \in k(x_0,\ldots,x_N)$

– reuns Dec 26 '17 at 06:29