This is a question that I have already asked on HSM stackexchange, and I decided to ask it again here because it is more mathematical than historic (to make a conclusion in this question one needs more mathematical then historical understanding). In p. 283-285 of volume 2 of Dickson's “history of the theory of numbers” appear several formulas of striking similarity: some of them are stated by Gauss (p.283) and some are stated by Jacobi (p.285); they are actually the same and only the notation differs ($x$ in Gauss's formula and $q$ in Jacobi's formula). Gauss's formulas are the following identities on the 4th power of the theta function:

$(\sum_{-\infty}^\infty q^{{n^2}})^4 = (\sum_{-\infty}^\infty (-1)^n q^{{n^2}})^4 + (\sum_{-\infty}^\infty q^{{(2n - 1)^2/4}})^4 = 1 + 8\sum_{1\le m} \frac {{mq^m}}{{1 - (-1)^{m + 1}q^m}} = 1 + \sum_{1 \le m}\hat \sigma (k)q^k$

The point is that the last equality means that the coefficients of the $k$th power in the right side of the last equallity must be equal to $r_4(k)$ (number of representations of $k$ as sum of $4$ squares), and an additonal interpretation (by certain manipulations) of the right side of the equallity gives the result of Jacobi: $r_4(k) = 8\sigma(k)$ or $24\sigma(k)$, depends if k is odd or even.

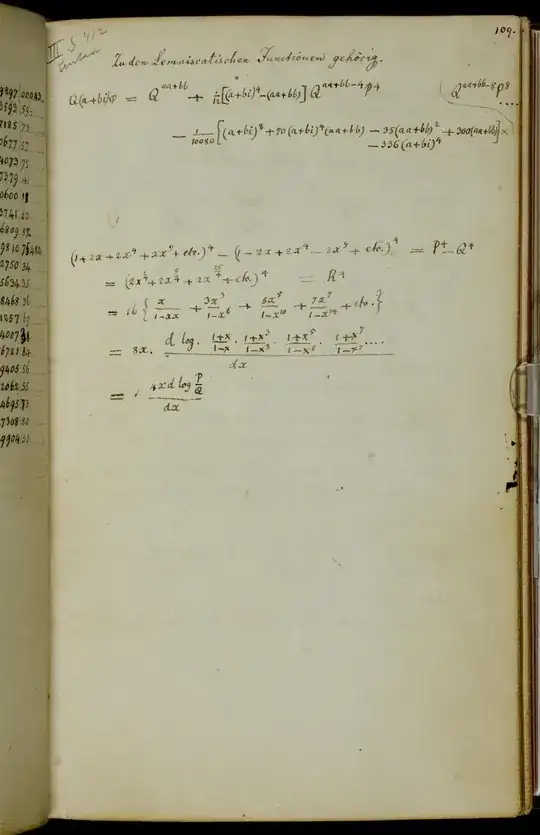

In the same passage from Gauss's nachlass (Werke, volume 3, p. 444-445, passage [9]) in which he writes down Jacobi's identity, and just before this identity, Gauss also writes down $\mathbb{log}(\vartheta_3^4(x))$ as:

$$\mathbb{log}((1+2x+2x^4+2x^9+\cdots)^4) = 8\cdot (\frac{x}{1+x}+\frac{x^3}{3(1+x^3)}+\frac{x^5}{5(1+x^5)}+\cdots)$$,

(actually he writes down the series for $\frac{1}{2}\mathbb{log}(\vartheta_3(x))$, but it is equivalent to what I wrote). Immediately after writing down several identities on the fourth powers of Jacobi theta functions $p,q,r$, Gauss proceeds and writes a differential equation satisfied by new variables $t,u$ (defined by : $t = \frac{1}{p^2}, u = \frac{1}{q^2}$) and their first, second and third derivatives (of $t,u$).

Since I'm unfamiliar with the theory of modular forms, I'm unable to see how Gauss arrived at this identity for $\mathbb{log}(\vartheta_3^4(x))$, nor I'm able to see how one can find the series developement of $\vartheta_3^4(x)$ from that of $\mathbb{log}(\vartheta_3^4(x))$. But maybe some of the mathematicians here who are familiar with modular forms can see the connection.

Update (July 23, 2022)

The identity for $\mathbb{log}(\vartheta_3(x))$ can be derived on the basis of Jacobi triple product indentity; it is essensially an expansion of the logarithm into a linear combination of Lambert series by transforming the logarithm of the infinite product form of the theta function (which is a special case of Jacobi triple product) into an infinite sum of logarithms. A detailed derivation of it can be found in this post.

But I believe the key to uncover the infinite series for $\vartheta^4_3(x)$ from that of $\mathbb{log}(\vartheta^4_3(x))$ is the differential equation Gauss writes at the end of passage 9 - he defines $t = \frac{1}{p^2}, u = \frac{1}{q^2}$ where $p = \vartheta_3(x), q = \vartheta_4(x)$ and then writes down several relations, and one of them is: $$\frac{u}{t}-\frac{t}{u}=2x(tu'-ut')$$ Rewriting it in terms of $p,q,r$, one gets: $$\frac{p^2}{q^2}-\frac{q^2}{p^2}=2x(tu'-ut')\implies \frac{p^4-q^4}{p^2q^2}=2x(tu'-ut')\implies p^4-q^4 = 2p^2q^2x(tu'-ut') \implies r^4 = \frac{2x}{tu}(tu'-ut')\implies r^4 = 2x(\frac{u'}{u}-\frac{t'}{t})\implies r^4 = 2x(\mathbb{log}'(u) - \mathbb{log}'(t))\implies r^4 = x\mathbb{log'}(\frac{u^2}{t^2}) = x\mathbb{log}'(\frac{p^4}{q^4})$$

I dont know how to prove this differential equation, but this development shows that it connects the logarithm of ratio of theta functions with the fourth power of another theta function ($r$), so this might be the original method Gauss used to arrive at the series for $\vartheta^4_3(x)$. In addition, since $q(x) = p(-x)$, the right side of the last equation, which is $$x(\mathbb{log}'(p(x)^4)-\mathbb{log}'(q(x)^4)) = x(\mathbb{log}'(p(x)^4)-\mathbb{log}'(p(-x)^4))$$, can be calculated on the basis of the series expansion for $\mathbb{log}(p(x))$. This produces Jacobi's identity for the generating function of $r^4(x)$. However, I still dont know how to derive the series for $p^4,q^4$, nor I am able to prove the differential equation stated by Gauss.