One thing I haven't seen mentioned yet: Equivalence relations give us a tool for removing distinctions we are not interested in, so that the ones we are studying are all that remain.

For example, in topology it is very common to construct a new topological space by gluing existing ones together. MJD touches on this, but didn't show the power. Look at a square sheet. I would like to glue the two sides together:

How do you do that in topology? By equivalence relation! If $S = [0,1]\times[0,1]$ is the square, then I define $$(x_0,y_0) \sim (x_1, y_1) \iff y_0 = y_1 \text { and } (x_0 = x_1 \text{ or } |x_0 - x_1| = 1)$$

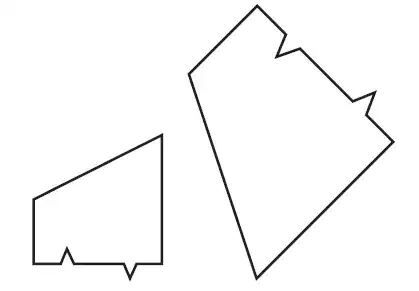

Points in the middle or top and bottom of the square are equivalent to only themselves, but points on the LH side is equivalent to points on the RH side at the same height. I drop to the set of equivalence classes $S/\sim$, and note that it has been proven that topologies are compatible with any equivalence relation, and I'm done! Just by putting together that equivalence relation, I've defined a cylinder complete with topology. But that isn't the end. With just a little twist, I get something different:

$$(x_0,y_0) \sim (x_1, y_1) \iff (x_0,y_0) = (x_1,y_1)\text{ or } (|x_0 - x_1| = 1 \text{ and } y_0 = 1 - y_1)$$

Now the space of equivalence classes is the Möbius strip, completely defined as a topological space by that little bit.

In the original square I had distinctions that were not desirable (LH side vs RH side). So I created an equivalence relation that ignored those distinctions. By passing to the equivalence classes, I have now gotten rid of the unwanted distinctions while keeping what is useful.

I can also glue the top and bottom sides together:

- if both top and bottom are glued straight and right and left are glued straight, you get the torus.

- if the top and bottom are glued straight, but the right and left are glued twisted, you get the Klein bottle.

- If both top and bottom and right and left are glued with twists, you get the projective plane.

And if you just make all boundary points equivalent to each other, then the entire boundary collapses to a single point, and you get the sphere.

This is just a tiny taste of the power of this technique. Every compact surface without boundary can be built by cutting a bunch of holes in a sphere, and then to each hole, either glue a torus with a single hole in it (gluing the borders of the two holes together), or else glue the border of a Möbius strip to the border of the hole.

Similar examples can be found in any field of mathematics. I was originally going to use building the tangent space in differential geometry, but switched to surfaces as being more accessible.

Equivalence relations are one of the most powerful tools in the mathematician's tool box. You will find them used everywhere.