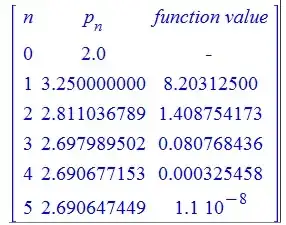

You are searching for the roots of a polynomial $p$. In this case it is possible to compute a running error bound for $p$, i.e. a number $\mu$ such that the computed value $\hat{y}$ of $y = p(x)$ satisfies $$|y - \hat{y}| \leq \mu u,$$ where $u$ is the unit round off error. When the error bound exceeds the absolute value of $\hat{y}$ there is no point in doing additional iterations.

The running error bound depends on the algorithm used to evaluate $p(x) = \sum_{i=0}^n a_i x^i$. Horner's method computes $$p_0 = a_n, \quad p_i = x p_{i-1} + a_{n-i}, \quad i = 1,2,\dotsc,n.$$ If $a_i$ and $x$ are machine numbers, then a running error bound can be computed concurrently as follows

$$\mu_0 = 0, \quad z_j = p_{j-1} x, \quad p_j = z_j + a_{n-j}, \quad \mu_j = \mu_{j-1} |x| + |z_j| + |p_j|, \quad j=1,2,\dotsc, n.$$

The algorithm returns $y = p_n$ and $\mu = \mu_n$. It is possible, to reduce the cost of this algorithm from 5n flops to 4n flops, but this is not a critical issue at this juncture.

In the general case where your function is not a polynomial you must proceed with caution.

Ideally, you merge a rapidly convergent routine such as Newton's method or the secant method with the bisection method and maintain a bracket around the root. If you trust the sign of the computed values of $y = f(x)$, then you have a robust way of estimating the error. Here a running error bound or interval arithmetic can be helpful.

I must caution you against using the correction $$\Delta x \approx - f'(x)/f(x)$$ as an error estimate. If $0 = f(x + \Delta x)$, then by Taylor's theorem

$$0 = f(x) + f'(x) \Delta x + \frac{1}{2} f''(\xi_x) (\Delta x)^2 $$ for some $\xi_x$ between $x$ and $x + \Delta x$. It follows, that $\Delta x \approx - f'(x)/f(x)$ is a good approximation only when the second order term can be ignored. This is frequently the case, but I would not count on it in general.

Occasionally, it is helpful to remember that Newton's method exhibits one sided convergence in the limit, i.e. if the root is a simple, then the residuals $f(x_n)$ eventually have the same sign. Deviation from this behavior indicates that you are pushing against the limitations imposed by floating point arithmetic.

EDIT: Newton's and other iterative methods are frequently terminated when either $$|f(x_n)| < \epsilon$$ or $$|x_n - x_{n-1}| < \delta$$

where $\epsilon$ and $\delta$ are user-defined thresholds. This is a dangerous practice which is unsuited for general purpose software. A specific example is the equation $$f(x) = 0,$$

where $f(x) = \exp(-\lambda x)$ and $\lambda > 0$. Obviously, there are no solutions, but this is not the point. Newton's method yields $$x_{n+1} = x_n + \frac{1}{\lambda} \rightarrow \infty, \quad n \rightarrow \infty$$

It follows that the residual will eventually drop below the user's threshold. Moreover, if $\lambda$ is large enough, then the routine will immediately exit "succesfully", because $x_{n+1} - x_n$ is small enough.

Writing a robust nonlinear solver is a nontrivial exercise. You have to maintain a bracket around the root. You must be able to trust at least the computed signs. To that end, the user must supply not only a function which computes $f$, but also a reliable error bound.