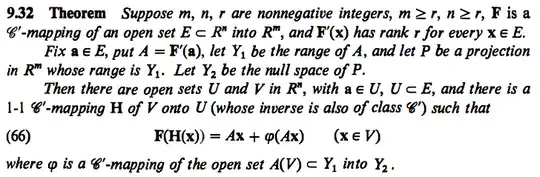

Intuition regarding the "rank theorem" in Rudin's Principle of Mathematical Analysis has been asked several times in this site:

I'm trying to understand how this theorem applies to the following example. Consider $F:{\bf R}^2\to{\bf R}$ with $$ F(x,y)=x^2+y^2 $$ So here we have $n=2$ and $m=r=1$. Take $a=(1,0)$. Then $A=[2,0]$ and thus $Y_1={\bf R}$ and $Y_2=\{0\}$.

Here are my questions:

- What should be $V$, $H$ and $\varphi$ for this example?

- What does the rank theorem really say about this example?